I recently did consulting work for a dive and kayak store. I asked the staff what they were really selling in the kayak section. The answer eventually came back that they were selling freedom. So what were they selling in the dive section? Everyone agreed they were selling belonging (to the club of divers).

What makes diving so different from kayaking is its emphasis on certification. Look around at what’s happening in the sea kayaking industry in Canada and you’ll see that formal certification is like a virus that has started to infect our sport too. The process gained momentum when Parks Canada recently demanded certification for kayak- ing guides, while in the field of kayak instruction, some companies are obliging their employees, who often earn little more than minimum wage, to pay up to $800 for in-house certification courses before they can work with clients on the water. And new schemes are cropping up everywhere to dole out certifications like boy scout badges to recreational paddlers.

Certification’s principal function, so far as I can tell, is to generate cash for rapacious bureaucracies. And the consequence for paddlers is that our favourite pastime shifts from a freedom activity to one of membership in an exclusive club administered by a hierarchy of bureaucrats with an inflated sense of their own importance and competence.

So what, you ask, is wrong with exclusive clubs? Well, a club divides us into two classes of people: those who are in and those who are not. Membership in these clubs depends upon passing a test. A layer of bureaucracy set- tles over the activity like a net, compromising freedom, which was the reason most of us took up sea kayaking.

“I’m free not to join a club if I just want to paddle,” you may say. Sure, but don’t count on it lasting.

Look at the dive industry. PADI, the Professional Association of Dive Instructors (a.k.a. Put Another Dollar In), controls every aspect of the sport by controlling retail outlets. You can’t buy or rent scuba equipment, or fill tanks, unless you have done one of their insidious modu- lar courses. Then every time you wish to advance, you have to pay for yet another module. Most dive shops won’t even sell you a drysuit unless you have done a drysuit course. By controlling and essentially taxing each step of the sport, they have virtually institutionalized personal responsibility!

Safety is usually the excuse for bringing in certification while fear, often combined with a sense of personal inade- quacy, are the base motivating emotions for going along with it. As a client to a kayak tour company, it may be reassuring to hear your guide is certified. If it could be demonstrated that the certification process produced bet- ter guides than non-coercive education through experienced-based training programs—something that NOLS and Outward Bound have proven can be done successfully—I might be more inclined to go along with it, but it doesn’t. There is no healthy reason for it.

Certification tends to emphasize what can be readily tested while neglecting less tangible yet more important issues like attitude and judgment that result from thought- ful responses to experience. Too often certification simply obscures a deficiency of real experience. Indeed because of the false sense of confidence the certificate generates and the deferral of institutional responsibility that results, it may actually make sea kayaking more dangerous.

Professional certification of guides and instructors acts as a mechanism for companies and land management bodies to avoid shouldering responsibilities that are right- ly part of their job description. For example, Parks Canada loves certification because it offloads responsibili- ty for assessing the competence of those who use the parks commercially. Insurance companies love certifica- tion because it covers their corporate asses and blurs legal responsibility. And some companies and colleges love certification because (they think) it lets them avoid taking responsibility for scrutinizing the competence of their staff—as in, “if he has a level four certificate he must be a competent guide/instructor.”

Professional certification is a golden opportunity for shrewd business operators and controlling personality types to hobble their competitors, artificially elevate their own personal status, and set up a toll bridge for guides and instructors. Good people reluctantly get dragged aboard out of their fear of being left behind or losing their jobs. Once certified, they are less likely to fight against it.

I foresee the day when, if we’re not careful, you won’t be able to rent or buy a recreational kayak unless you have your level one certificate, and if you want to buy a real sea kayak, you will need a level four certificate. No? Hey! Wake up! It happened to diving. It can happen to sea kayaking.

Resist certification while you still can.

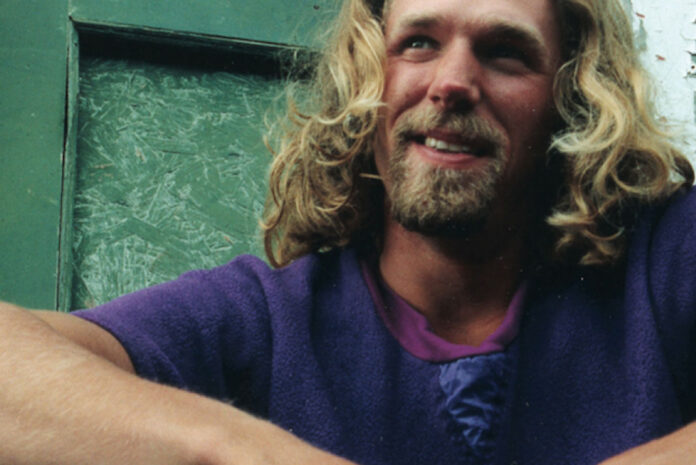

John Dowd is one of the founders of the sea kayaking industry. The fifth edition of his book Sea Kayaking has just been published. He is currently working on a new book about freedom and responsibility in the outdoors.

This article first appeared in the Late Summer 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Late Summer 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

1 View from the cockpit

1 View from the cockpit  This article first appeared in the Fall 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article was first published in the Summer 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.