Looking back, the American Canoe Association’s River Safety Report 1982–1985 is one of the more important artifacts in our relatively short and lightly-documented whitewater history. A paddling friend found a stained but otherwise decent copy in a used bookstore and left it on my doorstep. The thin volume makes for a fascinating read because, except for obvious improvements in equipment, very little about running rivers has changed in the last 35 years.

Why whitewater classification continues to embrace ambiguity

The book provides a snapshot of paddling via an unlikely medium; accident reports. The majority of these accidents resulted in fatalities, of which the echoes can still be heard today. Collected at a time when whitewater kayaking was just emerging from its fiberglass infancy in the 70’s to an adolescence driven by a plastic polyethylene revolution, this little booklet managed to capture a fringe group coming to terms with the risks inherent in our sport.

Edited by the venerable grand-daddy of river safety, Charlie Walbridge, the reports are succinct, honest and insightful. Some examples: A discussion of the “unusual mental fitness” required for running class V rapids, the near futility of rope rescue when dealing with a heads-down pinned kayaker, and the moral dilemma involved in offering to help a group of struggling paddlers make it to the take-out.

Even in these pre-Dancer days (the Perception Dancer being the boat that brought kayaking into its first boom beginning in 1986), the limits of the sport were well understood and, quite frankly, are mostly unchanged. All of the bread and butter classic runs, including the Gauley in West Virginia and Colorado’s Arkansas, were well traveled even by 1982. The majority of high-end difficult rivers even by today’s standards were already run.

A new look at an old problem

It was at the back of the booklet in the appendix that I took the most interest. A five-page piece entitled “River Classification—A new look at an old problem” essentially set the tone for managing risk in a way that we have all adopted and use today, perhaps without even knowing it.

The paper was intended to standardize our class I to V difficulty rating scale by benchmarking well-known runs against each other. The hope was to create equilibrium between a class III in New Mexico and a class III in Maine, or equate a class IV in Idaho with a class IV in Georgia. Whitewater paddling was regionalized up until this point, so this benchmarking movement was somewhat contentious.

Classification was first inspired by the already established mountaineering hiking route difficulty scale. Over the years, there have been proposals seeking to refine and specify a river scale that could account for gradient, volume and navigational hazards. None have caught on. More than 30 years later, the class I to V river classification system remains a bit vague with much room for interpretation, even though the descriptions themselves have barely changed since 1959.

The appendix is notable for its underlying message: Rivers are too complex to simplify into a number. Walbridge goes to great lengths in this piece to explain what a river classification cannot do. It cannot account for all of the variables of every river, for cold weather or poor paddling partners, nor for ego or ignorance. These themes are woven throughout the accident analyses that precede the discussion on river difficulty rating, and point to an ethic on risk now pervasive in whitewater.

“With this [class I to V scale] and a bit of healthy skepticism resulting from the realization that accurate classification is an elusive goal you should be able to stay out of trouble,” concludes Walbridge.

Walbridge plants responsibility firmly in the hands of the paddler to deal with every river on a rapid-by-rapid and hazard-by-hazard basis. Since then, rather than eliminate ambiguity, whitewater has grown to embrace it.

Our dynamic environment is what sets our activity apart from almost all others, and that elusive goal of standardization has more or less disappeared. What is left is every individual paddler’s choice to walk an easy rapid or to charge a hard one—either way it is up to individuals to decide for themselves.

Scout, come up with a plan, anticipate and accept what can go wrong and commit to that or come up with a plan B. None of this has changed from the earliest days of running whitewater.

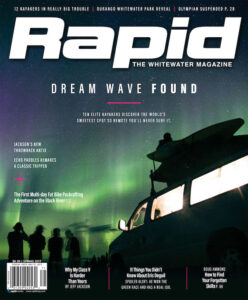

High tension on the Gatineau River. | Feature photo: Thiomas Fahran

This article was first published in the Spring 2017 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2017 issue of Rapid Magazine.