Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since I first apprenticed as a sea kayak instructor with Bruce Lash, a spunky firefighter who was among the first North Americans to earn the British Canoe Union’s vaunted 5-Star Sea award, which is regarded as the most rigorous sea kayak training in the world. Bruce liked to remind paddlers of all skill levels of the harsh, natural consequences of bad decisions on the water. He became especially animated when he launched into war stories of his own close calls, such as the time he ignored his intuition to bail out on an April trip on Lake Superior, then capsized multiple times in a harrowing surf launch from an icy beach and endured a three-hour tow from a fellow kayaker to reach safety through bungalow-sized swells.

Navigating the rising costs of wilderness rescue in an age of quick clicks

Bruce’s tales were always self-deprecating and humble, with the takeaway emphasizing that a paddler’s primary responsibility is sound judgment. Inevitably, as an afterword, Bruce would fetch a beach stick and drop to his knees on a patch of wet sand to draw out the “kayaker’s circles of safety,” which ultimately explained his error. He reinforced that the first line of defense—the outermost ring—was good judgment. From there, concentric circles ranked in order of importance: paddling skills, rescue skills, proper equipment and communication gear, and lastly, the will to survive.

But good judgment doesn’t score views on social media, evidenced by the growing number of hapless adventurers sharing moronic stunts with the world. In one example, New Yorkers Ethan Harold and Ammar Alkassm shocked locals last June by camping on an iceberg in Lobster Cove, near Twillingate, Newfoundland. The pair’s YouTube video depicts the friends’ road trip to The Rock with the goal of doing “something almost unheard of.” They assured the audience that they had “every small measure accounted for” before “rowing” an inflatable swim raft with kayak paddles to an iceberg and “mounting” the football field-sized expanse with ice cleats.

Then, they celebrated their feat with beer and instant noodles and spent the night fretting about polar bears in a pop-up tent that billowed in strong winds. The next morning, the pair’s sense of panic was obvious when the iceberg started breaking up, and they were forced to hastily slide off its surface into the North Atlantic, puncturing their raft with a cleat. Fortunately, they weren’t far from shore. The only upshot of the MTV Jackass-worthy video is that Harold and Alkassm’s channel has attracted fewer than 200 followers.

The dopamine hits of garnering likes on social media aren’t the only way technology is fueling a worrisome trend. Not so long ago, a VHF marine radio was the only option for two-way communication. Sketchy comms placed an immediate priority on solid decision-making and taking the time to hone paddling and rescue skills.

I can still terrify myself by conjuring the image of struggling in cold water, trying to unearth a handheld radio from my kayak’s day hatch, and hoping someone would hear my emergency call through the static of Channel 16. A friend of mine—whom I would describe as a skilled and responsible sea kayaker—perished in this exact scenario on a solo trip on Lake Superior’s Minnesota shore.

New tech brings unintended consequences

VHF marine radios have evolved to become smaller and waterproof, just as satellite messengers like Garmin inReach and SPOT have rendered radios virtually obsolete amongst today’s paddlers. What’s more, reliable cell phone signals now infiltrate once-remote coastlines. In the rare places without cell coverage, the latest iPhone features satellite capability to summon SOS assistance with the push of a button.

Saving your ass in the wilderness is easier than ever, and it seems inevitable that we’re on a fast track to a tragedy of the commons. Across much of North America, emergency rescue by the Coast Guard, military, national parks and volunteer organizations is generally offered free of charge—regardless of the poor decisions and sheer ignorance of paddlers, hikers and backcountry skiers. Emergency professionals would have risked their lives, and taxpayers would have footed the bill had Harold and Alkassm called for rescue.

“Having a phone or satellite device increases people’s comfort. It’s the easy button,” says John Blown of North Shore Rescue (NSR), a volunteer search and rescue organization in North Vancouver, B.C. “That never used to exist. It used to be that if you got injured in the backcountry, you were in a lot of trouble.”

“Having a phone or satellite device increases people’s comfort.

It’s the easy button.”– John Blown

Blown still stands behind the tradition of free rescues because victims may be discouraged from calling for help for fear of incurring costs. Delays can increase the risk to the subject and rescuers, and ultimately cost more, Blown says. Yet, the growing popularity of outdoor recreation and communications technology means NSR is busier than ever, responding to over 200 calls in 2021, compared to less than 40 in 1995. It’s a similar story with search and rescue teams across North America.

Weighing in on the iceberg campers, Canadian professional adventurer Will Gadd took a different tack, arguing the societal costs of risky behavior in the outdoors are still negligible compared to the strain of unhealthy lifestyles on public health care. “It’s like heart disease and depression. All that is very expensive,” Gadd told CBC. “I don’t really buy that argument on a cost basis.”

However, taxes also help compensate for the costs of vices like smoking and drinking. Some experts suggest it’s time for mandatory rescue insurance for backcountry users, the likes of which mountaineers must possess to do an expedition on Mount Everest. This may sound logical to some, but I find the contrast between insurance and the freedom of outdoor adventure deeply jarring. What about simply remembering the fundamental importance of taking responsibility for one’s actions? The best pathway to such an attitude might start with war stories and circles drawn in the sand.

Conor Mihell is a longtime contributor to Paddling Magazine. He kayaks on Lake Superior and paddles wild rivers in wood-canvas canoes.

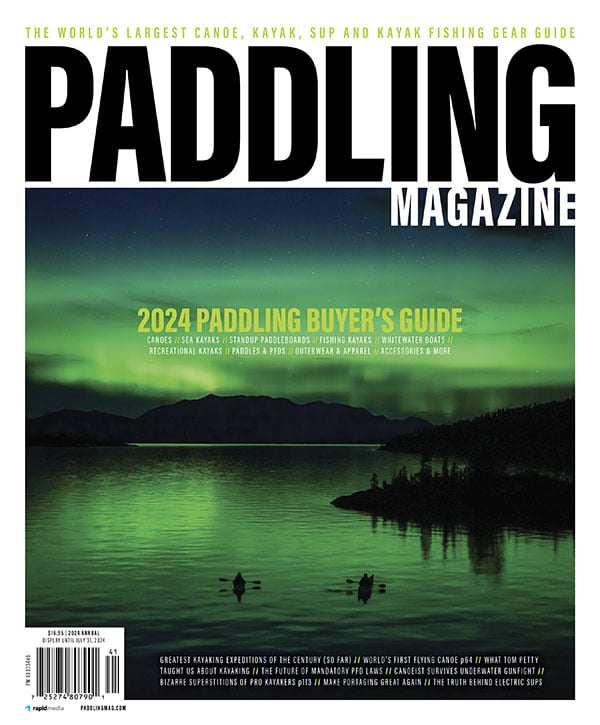

Every right has its responsibilities. | Feature photo: David Jackson

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.