Through my thirties and early forties I was feeling and looking pretty damned good. People would say that I looked 10 years younger. Then this year people suddenly stopped being surprised that I was 43. I didn’t just slide a few years; I instantly started looking my actual age. I gained a decade all at once.

Some callous schlub on the beach after a particularly grueling surf session even ventured to say, “It’s great you can still do that.” That comment haunts me. I’ll always remember this year as the first time I heard those words. Also the first year I couldn’t do everything better-faster-stronger than the year before—or make any sense of a McDonalds menu.

The year I turned 30 I paddled for 80 days down the British Columbia coast. My friend and I didn’t have a cell phone or a sat phone or an emergency beacon. Our first aid kit contained little more than duct tape and Band-Aids. We were young and just assumed that we’d be fine. And we were.

Blithe gallivanting into the world’s remotest reaches was the ultimate expression of youthful invincibility, vitality and fearless flouting of mortality.

We slept on the ground without an ache in the world. On rest days we’d rise and greet the day after a blissful 10 or 11 hours flaked out on primitive foam pads the same thickness and consistency as the vintage, gold foil-wrapped, sawdusty PowerBars we happily munched as part of our inconsequentially horrible diet.

Nowadays when I crash in a tent, I call it “sleeping” in quotation marks. It’s more like a nightlong meditation on which position offers the most relief from competing discomforts. In the words of Leonard Cohen, “I ache in the places that I used to play.” In my case, most of those places are in the wilderness.

Okay, so I know “going on 44” isn’t actually old. But the aches and pains I have already make me fear for what’s to come. At this rate, what will my camping future hold?

So many people I know have completely given up sleeping on the ground, or sitting in kayaks, because of sore hips, backs and shoulders. Already, health issues are greatly complicating the carefree wilderness experience.

That same friend I paddled the coast with turned 50 last year and had a small heart attack. For Christmas he got a brand new heart valve and a refurbished aorta. We used to talk about reuniting for another expedition, maybe on the coast of Chile. If we ever do, our emergency preparedness will look a lot different.

My great fear now that I have kids is that by the time I have the freedom to do long expeditions again, I’ll be too old. In the interim I have zealously instituted wilderness camping as a family tradition. My wife’s one condition was that I provision her with a collapsible chair and a portable camping mattress that packs to a size roughly equivalent to an additional child. I told her I was too embarrassed.

“Embarrassed in front of who?” she asked.

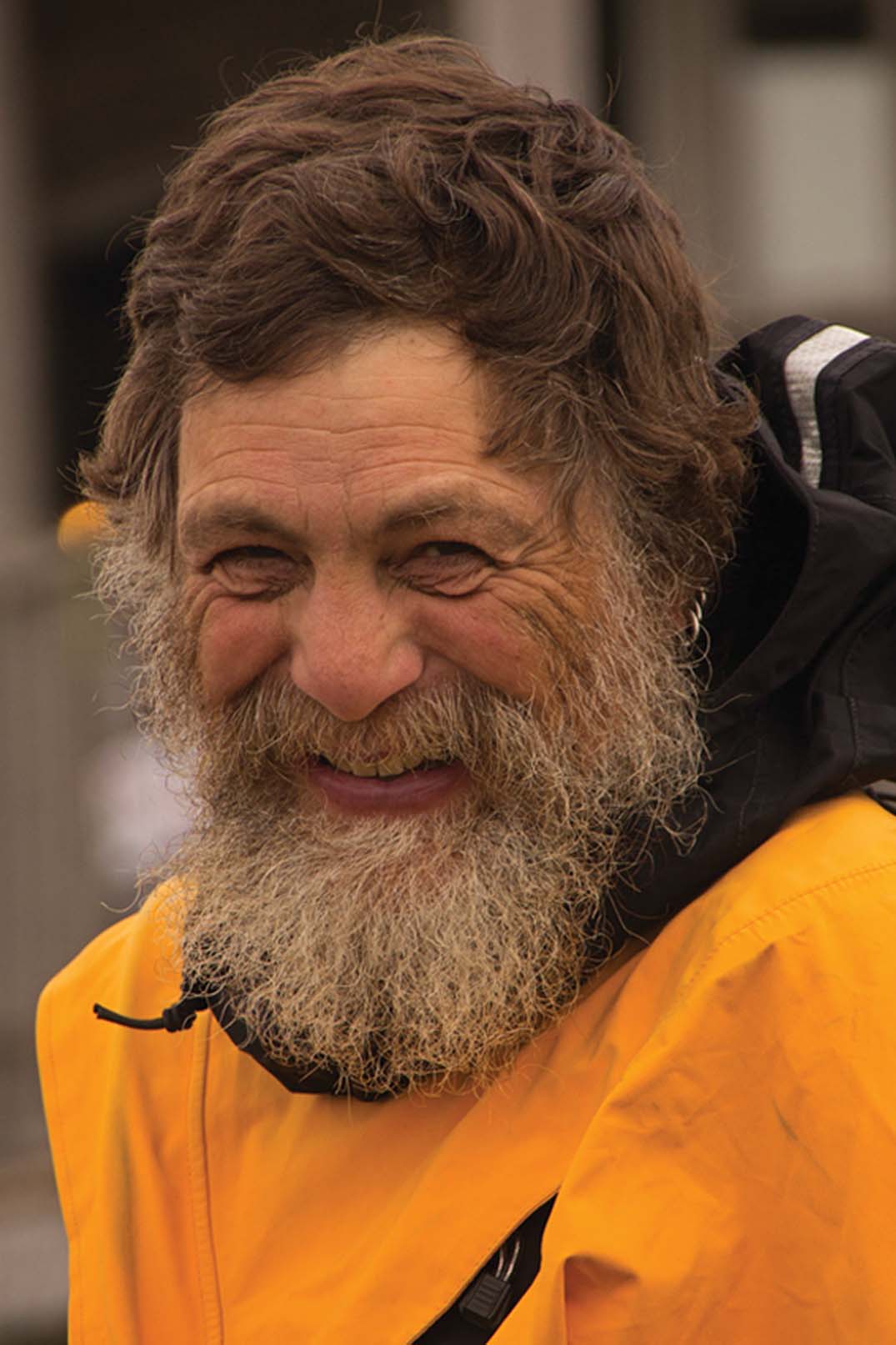

“In front of myself,” I said. I’m not the hirsute international expeditioneer I dreamed I’d become. But I sucked it up and bought the bleeping mattress. The saddest thing is that now I want one too.

Even at home we spend most days doing a complex regimen of physiotherapist-prescribed exercises, stretches and yoga routines to help us reclaim our lost limberness. By the time we get all warmed up, we’re feeling pretty good. Except every year the routines get longer, and I have to go to bed earlier.

Someday we’ll get to the point where the exercises aren’t over until bedtime. I’ll spend my whole life getting ready for activities I’ll never get around to doing. Come to think of it, that kind of describes my life now.

I’m more aware than ever that my days are numbered. It makes the call to adventure all the more urgent. As the British kayaker and journalist George Monbiot writes in Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea and Human Life, “Twice in one year I had heard the call—that high, wild note of exaltation—after a drought of sensation that had persisted since early adulthood; a drought I had come to accept as a condition of middle age, like the loss of the upper reaches of hearing.” I hear it now too.

Now going outdoors is less flouting mortality and more of a somber acceptance, an intensification of the psychological process of aging itself, coming to grips with that old process that I never thought would happen to me.

And yet there’s also the hope that wilderness has a kind of healing effect. On a family camping trip last summer, I woke up with back pain every morning, aggravated by all the unfamiliar paddling. Still, the sight of sunrise over the water and the brave act of throwing myself in for a plunge before breakfast was a tonic that made it easier to get going than a typical day at home, despite the added physical toil. Maybe this get-up-and-go is the secret; the answer is more camping, not less.

One close friend lent further hope when he recently reminded me that most of the ambitious wilderness travelers he knows are senior citizens. They’re the ones who have the time—even with all the physiotherapy exercises. When my own time comes, I’ll do whatever it takes to be out there with them.

Waterlines columnist Tim Shuff is a firefighter, freelance writer and former editor of Adventure Kayak who now packs plenty of Advil along with his Band-Aids.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.