It started with a few observations, then an offhand remark, and finally, a question: If wanderlust—or waterlust—often seems contagious, could it in fact be inherited? To learn the answer, we tracked down paddling explorers, entrepreneurs, photographers, historians and guides, from California to Baffin Island, who all share a common thread—families who adventure together.

Families who adventure together are thicker than water

1 Soul food

Lannie, Ralph, Emily & Albert Keller

“There was never any doubt in my mind that my parents were different,” laughs Albert Keller. “They chased an idea that most people thought was crazy, and they made it into something pretty great.”

In 1979, Ralph and Lannie Keller sold their photography business and put everything they had into a 50-acre parcel of waterfront land on remote Read Island in British Columbia’s Discovery Islands. The young couple dreamed of building an off-grid wilderness adventure lodge, and they landed in a battered aluminum skiff packed with tent, chainsaw, lopping shears, spinning wheel, transistor radio and a handful of other simple tools, eager to start their coastal homestead.

The work was hard and never-ending: clearing building sites for a home and lodge, gardens and outbuildings; milling lumber from salvaged cedar logs; developing and maintaining systems for water, communications and electricity using solar and micro hydro power; and growing their own food. Then, in 1985, Emily was born, joined three years later by Albert. Determined to make a living where they lived, Lannie and Ralph welcomed their first guests to Coast Mountain Lodge nearly a decade after arriving on the island.

Juggling the demands of their fledgling business, young family and the endless chores of a “remote-island-off-grid-make-and-do-everything-yourself-lifestyle” was an ongoing challenge, says Lannie. “We worked way too much. We never had much money and we had secondhand everything. But we lived in an incredible place and every day was an adventure.”

In winter, the family three-wheeler ATV shuttled the children through dripping coastal forest to school—a one-room affair with just 10 students, where wolves were sometimes spotted on the playground. The steep patch of yard between the Kellers’ home and the ocean was a favorite sledding run, and on the coldest days, the family churned ice cream outside, “when we had the ice to make it.”

Summers were busy with Ralph guiding kayaking trips and Lannie minding the lodge and gardens. Albert and his sister developed a self-reliance that mirrored their parents.

“People who are raised in a wilderness setting have a ‘buck stops here’ attitude,” Ralph says. “They tend to take control of events around them without waiting for someone else to give directions.”

The Keller children certainly seem to be proof of this theory. Emily, 31, pursued a Masters degree and now lives in Vancouver, working as an environmental and social activist with the David Suzuki Foundation. Albert, 28, took the paddling course set by his parents, and molded it into something unmistakably his own.

At age eight, Albert declared he was accompanying his dad on a four-day commercial kayak trip to the Octopus Islands—paddling his own single kayak. The determined third-grader never fell behind the adults, marvels Lannie. Then, when Albert was 12, a promotional copy of Rapid magazine arrived in the mail.

“Whitewater kayaking came into my life at an opportune time,” recalls Albert, “I was just starting to write off sea kayaking as a dorky ‘old person sport.’”

He buckled down, mowing the lawn, washing kayaks and doing any job around the lodge to earn enough money to buy his own whitewater kayak. Albert honed his skills every weekend on the rivers of Vancouver Island, aided by a fraternity of older paddlers who welcomed the youngster into their fold. In return, he brought his friends to the tidal rapids of Surge Narrows and Okisollo Channel, which doglegs among the islands northwest of Read.

The Kellers embraced their son’s whitewater fixation, enrolling Albert in courses and traveling to festivals when they could sneak away from their business, which expanded in 2001 to include a second guesthouse, Discovery Islands Lodge on neighboring Quadra Island. “My mom used to bake cookies for me to take to the river,” recalls Albert. “People still complain that I never show up to the put-in with cookies anymore!”

Later, teaching paddling skills and leading trips with the family business, Albert’s prowess in a kayak caught the attention of well-known visiting sea kayakers like former surf kayak world champion, Sean Morley, and The Hurricane Riders’ Rowan Gloag. “He changed the way I surf,” attests Gloag, who describes Albert as “an under-the-radar prodigy on a wave.”

As humble as he is comfortable in a kayak, Albert prefers to keep a low profile, brushing off competition opportunities and perfecting his paddling technique simply for fun and personal reward. “If I’m in a beautiful place with good people, I’m happy,” he says.

“I wouldn’t trade my upbringing for anything. Growing up on Read Island gave me a deep appreciation for the natural world that has guided my life choices. I’ve never felt a need to follow any sort of traditional life path. There’s a freedom in that.”

2 Born to be wild

John Lockwood & Freya Fennwood

“Leisure is the luxury of kayak touring. If a trip is advertised as taking six days, we take twelve. Every day, my dad exercises his extreme talent at power lounging, preferably in blazing sun with his Pygmy Boats cap perched over his eyes…”

So wrote Freya Fennwood in 2004 during a father-daughter kayaking trip through British Columbia’s Bowron Lakes, a chain of 11 lakes surrounded by snowcapped peaks and connected by moose-trodden portages and milky glacial rivers. At 16 years old, the diminutive teenager was already a seasoned tripper with a wilderness paddling résumé stretching as long as her untamed caramel mane.

At six, Freya and the family black Lab shared the bow cockpit of a triple kayak helmed by her father, Pygmy Boats founder John Lockwood, on Montana’s wild and scenic Missouri River. At seven, she joined her parents for a month-long journey by VW camper van and wherry, rowing the small boat back through the Bowron Lakes and down the badlands valley of the Red Deer River, hunting for dinosaur fossils. The following spring, the family kayaked the red rock canyons of Utah’s Green River; at nine, Freya flew to Canada’s Northwest Territories to meet her father for a two-week trip in the sub-Arctic, paddling her own 13-foot kayak designed by Lockwood especially for his daughter.

“Kayaking has been in my life a very long time,” says Freya, now 28. One of her earliest memories is that of a sensation: “Seated in my dad’s lap, the paddle moving back and forth in front of me, and the kayak rocking a little bit with each stroke.”

In fact, Freya’s connection to kayaking can be traced to six months before she was born. That’s when Lockwood and mom-to-be Freida Fenn moved to the small coastal community of Port Townsend, Washington, and set up a one-man wooden kayak manufacturing shop called Pygmy Boats. The name reflected Lockwood’s admiration for the peaceful hunter-gatherers he’d studied as an anthropology major at Harvard in the late 1960s.

“Freya was raised like a pygmy,” says Lockwood, 73. “She was a little Paleo baby and the most joyous infant, toddler and child I’ve ever seen. She continues to be the most joyous person I know, and of the many things I’m proud of her for, I’m most proud of that.”

What some parents might view as irresponsible, Freya’s saw as natural opportunities for discovery and self-driven learning. As an infant, she was in rapture of the pebble beach at Pygmy Boats, touching and tasting everything within reach. “Her mother and I had an agreement that we would not take anything away from her or out of her mouth unless it was actively poisonous,” says Lockwood. After all, what better nursery could there be than the endlessly fascinating, challenging and astonishing natural world?

“That power to just pick up and learn things is one of the greatest gifts my parents gave me.”

“That power to just pick up and learn things is one of the greatest gifts my parents gave me,” says Freya. “They dared to home school me, to let me be a wild child running barefoot through the boat yard, and to protect me from a lot of nasty, naysaying, shoe-demanding people who liked to say ‘no, you can’t climb that, can’t do that.’”

With its Paleo routine of sleeping together in a tiny shelter, cooking over a fire and spending entire days outdoors, wilderness camping quickly became a favorite family tradition. Lockwood chose wild yet safe waterways for these adventures, where the goals were to “wander, lie on the beach, fish, swim, explore, to see what happens, to be at ease.” Even the inevitable hardships—torrential rain, flooding rivers, throngs of mosquitoes—young Freya took in stride.

During an earth-shaking storm on the Green River, Freida Fenn recalls her eight-year-old daughter sleeping soundly through the night as 50-mile-per-hour winds collapsed tent poles and lightning sheeted across the sky. “I shall always see her joy in facing the wind, waves, whirlpools and bucking current,” Fenn says of that trip, “and her shout, ‘Let’s go there, Papa!’ pointing at nature’s next red rock wonder.”

Since those early trips, Lockwood has watched his daughter grow into an accomplished paddler, freelance adventure photographer and world traveler. “Sometimes I think he wishes I would just settle down and run his company,” muses Freya, “but the example he set was to explore and see the world.”

Four years ago, father and daughter’s passions for paddling and world-wandering dovetailed in a project that would bring them nearly full circle to the little girl who hopped a jet to Yellowknife to paddle with her dad beneath the northern lights. Freya had discovered a love, and remarkable talent, for kayak rolling. When renowned rolling coach Dubside suggested Freya compete in the Greenland National Kayaking Championships, Lockwood promised his daughter, “I’ll make you a kayak that is sized for you and designed specifically for rolling, and we’ll take it to Greenland together.”

Four prototypes and nearly three years of testing, brainstorming and redesigning later, the Freya was ready.

“Greenland was an amazing culmination of a really fun collaboration,” says Freya. “I couldn’t believe I was paddling in the birthplace of kayaking with my dad, the person who introduced me to kayaking when I was just a baby in his lap, rocking to the waves on the hull.”

3 First, faster, further

Brian, Rosemary, Graham & Russell Henry

“The life we’ve made was my dream, and I’m just lucky those guys wanted to come along.”

The “guys” whom West Coast sea kayak pioneer Brian Henry is referring to are his family: wife Rosemary and sons Graham, 25, and Russell, 24.

It was 1981 when Henry founded Ocean River Sports, Vancouver Island’s first kayak shop. In those days, “If you saw boats on a car, you knew whose they were,” says the Victoria-based entrepreneur. Within a few short years, however, the sport exploded. Henry couldn’t get enough boats to keep pace with demand, so he launched Current Designs in 1984 and started building his own kayaks. He met his wife-to-be when she walked into Ocean River and bought a boat.

Running two growing businesses and raising a family was challenging, admits Henry, “but we never stopped doing what we wanted to do because of kids.”

Inspired by his petite wife, Henry designed a smaller version of Current Designs’ popular Solstice kayak for Rosemary, becoming the first company to create different-sized boats for different-sized paddlers. To accommodate his young sons, Henry drafted the Libra XT, a roomy triple with a center cockpit seat that suspended above the rear paddler’s legs. In this outfit, the family of four comfortably paddled a single kayak: Rosemary wearing Russell in a snuggly in the bow, Graham in the middle and Henry in the stern.

“We were a bit of an anomaly. People would ask, ‘Wow, you’re teaching your kids kayaking?’” recalls Rosemary. “Some parents teach their kids to ski at two years old, we taught ours to paddle.”

Every year, the family set off for a weeklong trip exploring Vancouver Island’s wild coast—the Broken Group, Deer Group, Nuchatliz, Winter Cove. “We’d go to remote places other people weren’t necessarily comfortable with,” says Henry. Being pinned down for a couple of days by wind or waves might be off-putting for some families, but for the Henrys it was simply part of the paddling experience.

“I’m a big believer that you can coddle kids to the point that they don’t really experience anything,” continues Henry. “We encouraged them to stretch their limits, but they were never in danger…just a little discomfort maybe.”

Of course, there were occasional mishaps, like the time baby Graham tumbled out of a paddling friend’s lap, who then “scooped him up like a coho salmon,” soggy but none the worse for wear. Or when Rosemary noticed that Russell, just a few weeks old on his first kayaking trip, was unhappy when the wind was in his face. “Apparently very young babies hold their breath in the wind.”

Dad’s advice wasn’t always welcome, but it was usually sound, recall the brothers. Henry’s calm assurance, “You will be fine,” saw the boys over enough hurdles that the phrase became something of a family joke. When Henry took his 14- and 15-year-old sons to surf Skookumchuck tidal rapids, the brothers remember it being the most terrifying thing they’d ever done. But Dad said, “You will be fine,” and they were.

That faith has led the brothers on some remarkable journeys. In early 2014, they completed a seven-month, 4,000-mile kayaking expedition from Brazil to Florida, making them the first to paddle across the Caribbean since John Dowd’s 1979 crossing.

Hot on that expedition’s heels, Russell set out to attempt a new speed record for paddling 750 miles around Vancouver Island. Kayaking solo, he shattered the previous record by more than two-and-a-half days. It was Henry’s suggestion to take advantage of strong northwesterly winds by starting from the top of the island, rather than the south end as planned, that gave Russell a critical lead on the world record.

“Dad is just so darn stoked on our trips, he’ll come up with crazy solutions to problems and talk like he’s coming along,” Russell says of his father’s role in the brothers’ adventures.

Last summer, Russell and Graham teamed up for another ambitious first: competing in the inaugural Race to Alaska, a grueling 700-mile transit of the entire British Columbia coast. Enlisting four friends and a six-person canoe, they braved 40-knot winds and steep seas to become the race’s first paddle craft to reach Ketchikan.

Both Russell and Graham agree the greatest gift they received from their parents was freedom. “Most parents would say ‘no, don’t do that,’” explains Graham. “Ours would ask, ‘are you sure you want to do that?’ then let us do it. When someone gives you trust like that, you are aware of that responsibility.”

There’s another responsibility he is well aware of—his father’s business. “Pretty much everyone in my life asks, ‘Are you going to take over the shop?’” says Graham, who worked three summers at Ocean River before starting an environmental law degree. “As much as it’s something I enjoy, that was kind of my dad’s career and his adventure.”

Russell is equally independent, happily steering his own course of “paddling, ski bumming and instructing kids in the outdoors.” Both boys admire their parents’ fearlessness to dive into new projects. Rosemary recently earned her ski instructor certification and Henry is busy with new kayak tours for Ocean River’s growing tourism business.

Where does this energy to pioneer industry, smash records, win races, complete daunting expeditions and continually reinvent come from? Henry’s best guess: “It’s in our genes.”

4 Frozen footsteps

Matty McNair, Paul Landry, Eric & Sarah McNair-Landry

Sarah McNair-Landry and her older brother, Eric, grew up listening to stories from their parents’ expedition around Baffin Island. In 1990, traveling 4,000 kilometers by dogsled over land and sea ice, Matty McNair and Paul Landry became the first to circumnavigate this inhospitable island in the Canadian Arctic. The journey established the couple as professional polar explorers, and was equally pivotal on the home front. “They absolutely fell in love with Baffin,” Sarah says, “and decided to move here, to call it home.”

Living on the edge of Frobisher Bay in Iqaluit “where you step outside and it’s -30°C much of the year,” and growing up with renowned polar expedition guides for parents and all of Baffin Island as your playground, “is like everyday training,” says Sarah, now 30 and a respected Arctic adventurer in her own right. She and Eric, 31, quickly learned how to deal with the cold and be comfortable outside. “From as young as I can remember, we would get loaded up in so much outdoor gear that we could hardly move, and packed onto the dogsled for a day or overnight camping trip,” she says.

“We took Sarah and Eric out on the land as often as we could,” confirms Landry, who along with McNair logged countless backcountry days as a long-time wilderness survival and leadership instructor at Outward Bound before making the move north. “Day outings led to overnight trips and then to longer multi-day trips and two-week-long trips.”

When Sarah was 17, that progression led to the family’s first major expedition together—a four-week dogsled, ski and kite-ski across the Greenland ice cap. “Expeditions were part of our lifestyle and part of our work, so it was natural for Sarah and Eric to be part of that,” explains Landry, who was confident the teens were up to the challenge. “They had lots of experience in the cold, winter camping and working with dogs. Kite-skiing was new to all of us, so we were learning together.”

Skipping out of high school a month early to spend weeks alone with your parents in a remote deep-freeze isn’t your average teenager’s idea of a good time. But the McNair-Landrys reveled in the physicality and isolation.

“I was hooked,” says Sarah.

The following year, the siblings joined their mom on a three-month, self-supported expedition skiing to the South Pole and kite-skiing back across Antarctica’s barren snowfields. “That was a hard trip both physically and emotionally,” says McNair, whose relationship with Landry had just come to an end.

At 19, Sarah helped her father guide two clients on a 100-day expedition dogsledding from Russia to the North Pole and back to Canada, making her the youngest person to travel to both poles.

“After those trips, my brother and I started planning and heading out on our own adventures,” says Sarah.

In 2007, the siblings completed a kite-ski traverse of the Greenland ice cap from south to north. In 2009, they sailed three-wheeled buggies across the Gobi Desert; in 2010, they paddled canoes 2,000 kilometers through the rivers and lakes of Russia and Mongolia. Returning to Arctic travel in 2011, the pair kite-skied 3,300 kilometers across the Northwest Passage—an 85-day winter trip fraught with unstable sea ice and a harrowing polar bear encounter. Two years later, Eric and Sarah built their own traditional Inuit style kayaks and paddled and portaged 1,000 kilometers across Baffin Island. To these achievements, they’ve also added commercial guiding gigs throughout the polar regions.

As his children’s adventures have grown more ambitious, Landry admits it is difficult being a parent and a polar specialist. “I am familiar with the dangers and risks,” he explains, “I know what it’s like being out there.”

McNair echoes those concerns, “They have the knowledge and experience to make good decisions…but there are always the unpredictable polar bears and shifting ice conditions.”

So it is hard to imagine the pride and trepidation that Landry and McNair must have felt when Sarah announced her latest expedition plans: commemorating the 25th anniversary of her parents’ Baffin Island circumnavigation by retracing their dogsled route with her own team of 16 huskies. No one better understood the difficulties Sarah and her partner, Erik Boomer, would face on the monumental 120-day journey.

In fact, traveling with her parents’ trip journals, Sarah noticed frequent similarities between their hardships and her own 12-hour days on the trail. “I gained so much more respect for my parents’ expedition after retracing it,” she says.

A quarter-century after Baffin Island’s frigid grandeur stole McNair and Landry’s hearts, it continues to enthrall their children.

“What I’ve loved most about growing up and living on Baffin Island is the access to the backcountry,” Sarah enthuses. “The Arctic Ocean is out my back door, I have my team of dogs, and there are endless places to play and explore.”

5 Guiding powers

Michael & Marika Powers

“I don’t want to be cute anymore, I want to be tough and brave.”

Michael Powers still chuckles when he remembers his three-year-old daughter, Marika, uttering these words. Adventure Kayak caught up with the elder Powers, 76, from California’s Miramar Beach, where he’s lived in a Viking-style home of his own creation, facing the Pacific for the past 47 years.

Best known for his exploits with the Tsunami Rangers, a group of pioneering extreme conditions sea kayakers who hit their heyday in the ‘90s and early 2000s (“We’re kind of over the hill now,” he admits), Powers has also made some remarkable journeys with his equally adventurous daughter. When Marika isn’t busy guiding wilderness expeditions in Alaska, Baja, Costa Rica and Hawaii, she joins her father for ambitious trips all over the world. Together, they’ve made two multi-sport crossings of Patagonia, explored Cuba, paddled Mavericks and Alaska’s Tracy Arm Fiord, and much else.

“My parents filled my childhood with wonder and even a little magic,” Marika says. “They lived unconventional lives and gave me perspective and experiences outside the norm.”

Father and daughter share some of those insights and discoveries:

ON FAMILY LIFE

Marika: Growing up, I realized that my family life was different, but not that it was special until I was older. I remember being totally embarrassed at my father clad in animal skins, running around like a wild man.

Michael: I was immature myself when I had kids. I wasn’t the solid, patriarchal example. My own upbringing had very little stability; I went to 14 different schools in half-a-dozen states before high school. Marika is the same way as me—unconventional, adventurous—and probably for the same reasons. There’s always a trade-off. You can’t be an outdoor guide and a family patriarch.

ON PARENTING

Marika: My father was more relaxed in his parenting; my mother had to maintain a watchful eye to ensure no loss of limbs.

Michael: I’m not in Tsunami Rangers mode on trips with Marika. We’ve swum, we’ve been uncomfortable, but she’s never been hurt on our adventures.

ON KAYAKING

Marika: My father took me on my first kayaking trip, and I hated it. Totally traumatizing. We flipped multiple times. I remember him holding onto his camera bag with one hand and his freaked out seven-year-old with the other, floating down the middle of the river.

Michael: I had just gotten into kayaking and I read about the East Carson River, which flows out of the Sierras into the Carson Desert. The article said it would be easy class II, but it was actually pretty challenging. We were novices; I had these little inflatable boats, no helmets, no life vests. It was a two-day trip, with a camp out at a hot springs. I shudder now to think how ill-prepared we were. Marika didn’t hold it against me, though.

ON PUTTING DOWN ROOTS

Marika: I love being out in Alaska. I feel most content out there, and while I don’t ‘live’ anywhere, coming back to Alaska always feels like coming home.

Michael: I’ve expressed my concern to Marika that she’s 40 and hasn’t got a home, you know, ‘Where do old guides go?’ I’d like to see her have roots. She just tells me, ‘I like my life.’ There’s a Spanish saying—paso a paso—which means step-by-step. To stay in the moment—that’s been my philosophy and it’s hers as well.

6 Creation stories

Harvey & Steven Golden

Kayak historian Harvey Golden happened upon his vocation through a serendipitous intersection of providence and paternal support.

Back in 1991, having spent three years at Oregon State University pursuing a literature degree, Golden realized he wasn’t where he wanted to be, dropped out of college, moved back in with his parents, and fell into a depression. Months passed. The melancholy deepened. Concerned, Golden’s father, Steven, a lifelong tinkerer and outdoorsman, wracked his brain hoping to devise some means of lifting his son out of the funk. But, try as he may, nothing worked.

Then something happened.

“I came home one evening and Harvey was rummaging around in the garage, which was unusual, as for the past few months he hadn’t been doing anything much at all,” remembers Steven. “When I approached him, he looked different—very determined. When I asked what was up, he told me he was building a kayak.”

Determined to assist in any way he could, and being a hobbyist woodworker himself, Steven offered to help.

“I’d stumbled upon a schematic drawing of a historic kayak from Greenland at a friend’s house,” says Golden, recalling the fortuitous impetus behind his first build. “At the time, I had this deep inkling about water, didn’t have any money and didn’t know what to do with myself. When I saw the plans, for whatever reason, something in me said, ‘You have to build that boat.’”

Over the course of the coming months, father and son salvaged materials and constructed their handmade wood-framed kayak. On the morning after the boat’s completion, Golden told his father that he’d like to take the maiden voyage alone.

“I was a little disappointed,” admits Steven. “But it was Harvey’s adventure, and my role was one of support.”

Confronted by the jarringly cold Pacific Ocean, struggling to remain upright in the tippy craft, Golden remembers feeling suddenly very alive, very free.

“It was like I’d subconsciously allowed the adage ‘steering your own ship’ to be taken completely literally,” he laughs. “The kayak was such an intimate craft—it was just me and the boat, alone on the water. I realized I’d created this experience for myself and it was wildly empowering.”

Later, as the sun disappeared beyond the ocean, Golden remembers thinking: These boats had to have come from somewhere…

“I was seized by this great need to know the kayak’s original purpose,” he says,”what the first versions looked like, how they were built, what they were used for, where they came from.”

In the 25 years following his coastal epiphany, Golden, now 45, devoted himself to not only investigating the historical development of kayaks and kayaking throughout the northern hemisphere, but to reconstructing precise replicas of the crafts he so diligently researches.

Golden’s quest has led him on numerous archaeological digs, anthropological expeditions and Arctic kayaking adventures throughout Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Canada and Alaska. He’s written two 500-plus-page tomes—titled, respectively, Kayaks of Greenland: The History and Development of the Greenlandic Hunting Kayak, 1600–2000 (published 1999) and Kayaks of Alaska (published January 2016)—with a third volume on the historic kayaks of northeastern Canada presently underway. He’s traveled to the storage rooms of museums all over the world, and ultimately founded his own replica museum in Portland, Oregon. And, of course, he’s built lots more kayaks—replicating over 200 ancient skin-on-frame designs.

“By the time Harvey got his boat out of the water that first day, he was already planning his next build,” chuckles Steven. “It was amazing to watch what I assumed would be a passing hobby transform into a passionate career.”

Indeed, within days of returning from his first outing, Golden says he’d scoured library stacks, borrowed books on ancient kayaks, selected a model, sought out schematic drawings and begun making plans for the next vessel. “Since then, I think I’ve constantly had a replica underway— and most of the time, two or three. It’s become something of an obsession.”

Looking back, this acclaimed historian identifies his outdoor-rich childhood as the substrate from which the fixation sprang.

Two years after Golden was born, Steven and his wife, Nancy, decided they didn’t want to raise their children in the city and made the drastic move from Los Angeles to the rural, river-rich coastal range of Oregon.

“If not for that decision, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing,” he says. “I wouldn’t have had the experiential vocabulary that’s made it possible.” —Eric J. Wallace

Feature photo: Courtesy Pygmy Boats archives

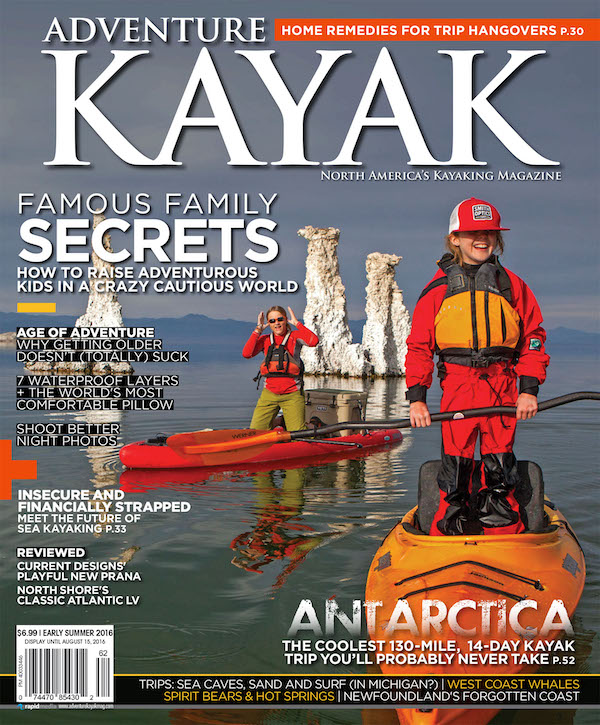

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.