There were whispers around camp that there was something otherworldly about him. Some said he was a Wendigo, the semi-human cannibalistic beast from native legend. How else could a man so large—dressed in an orange jumpsuit no less—drift through the woods so quietly that he could appear behind you just as you were bundle planting or balling up a root system and cramming it into the ground?

The sins of bundle planting and root balling aren’t important outside the world of treeplanting, but they were important to Dane. He was the forester charged with making sure we were planting trees that would grow. Dane could make you replant a day’s worth of trees. On top of that he had a moustache all the guys admired and he knew his way around the bush. He was the guy you wanted to have around if the ATV got stuck in a sinkhole. Though probably not a cannibal, Dane commanded respect.

I suspect he can’t paint as well as Tom Thompson, and no doubt Esther Keyser knows better campsites, but Dane the logger is the Algonquin Park icon that springs to my mind when someone mentions the park.

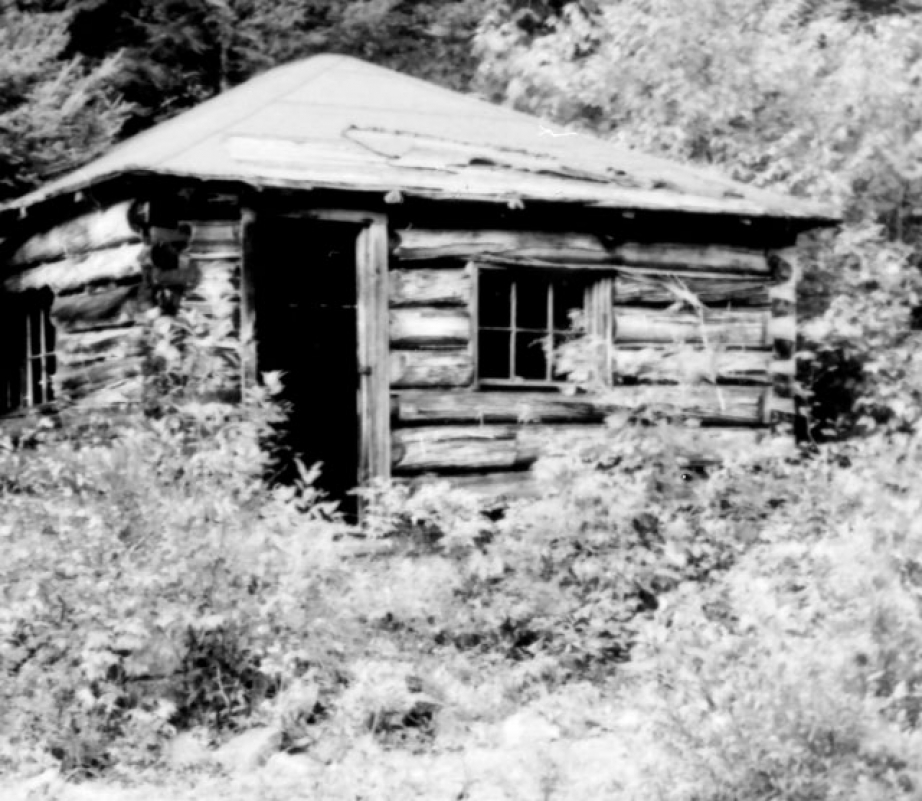

I’ve spent far more time in Algonquin Park with a shovel in hand than a paddle. During three seasons treeplanting there I bounced along many of the park’s 8,000 kilometres of logging roads with a foreman at the wheel, testing the limits of our van’s suspension and stereo systems. I rode to work every morning with my face against the window, grabbing glimpses of lakes that would have been better viewed from a canoe.

I proved skilled at hiding my planting gear where my foreman couldn’t see it so I could sneak through the buffer of trees between logged areas and lakes. Sitting on the shore I would feel the callouses on my hands and think of how easy it would be to put in a 40-kilometre day.

Once a week we passed the park gate on our way to Pembroke for a day off. I often imagined stopping and changing the name to Algonquin Tree Farm. I thought people should know that 78 per cent of the park is logged.

My dreams of criminal activism went unfulfilled and the sign remained unmolested. Ten years later there is an easier way to register my opinion. Ontario’s Minister of Natural Resources recently asked the Ontario Parks Board to propose ways to reduce logging in Algonquin Park. The board suggested an increase in the amount of park land that is actually given park-like protection from the current 22 per cent to 46 per cent. If approved, almost half of Algonquin could soon be off limits to logging. The MNR expects there will be public consultations when the minister proposes making the change official.

I think I know what sort of consultation Dane would offer the minister. Dane once gave me the impression that, to him, the trees of Algonquin didn’t just look good on a postcard, their pulp would look good in the postcard.

Dane might tell the minister that Algonquin was initially created to keep homesteaders and settlements away from the valuable wood supply, not the canoe routes we’ve since scribed on a map.

He might also tell the minister that good people in towns just like the one this magazine is based in rely on logging in the park for their livelihood.

That’s a tougher one to answer, but the minister could point out that even with these changes more than half of the park will retain its tree farm function.

The minister could also point out that these changes might save some money in maintenance costs if would-be vandals are less inspired to deface park signs to point out what goes on behind the gates of this supposed sanctuary of provincial wilderness. After all, it’s not just the park gates that have signs. There’s a sign on the road leaving the Toronto airport telling all the tourists that fly here for the wilderness we have left that they are only 252 kilometres from a park that is becoming less and less like a tree farm.