The bones of countless battered Prospector canoes have rotted to dust on empty shorelines over the last century, but many more have died quietly in city backyards and northern lots, their adventure-seeking owners having long since done their own version of returning to dust.

The Prospector has been the workhorse of the wilderness for more than eight decades, and its reputation has become rich like aged cedar, as the stories and trip reports of one generation have become the legends of the next.

But what is a Prospector? And more to the point, can all past and present versions labeled as Prospectors be much like the real thing?

How the Prospector became canoeing’s most enduring design

Prospectors came into being to meet the needs of an industrializing country and the urges of its citizens to travel, explore and ultimately exploit the Precambrian Shield. According to Roger MacGregor, author of When the Chestnut Was in Flower, it was designed to service railway survey companies, timber cruisers, trappers and men with wide-eyed Gold Fever. It was popular because it was good at what it did. And what it did was work hard.

It was, and is, in essence a high-capacity gear-hauler; a wilderness transporter with lots of freeboard that was designed to be paddled loaded. Even the shorter 16-foot version could take you “out” for a month or more. Its classic construction was a complex, time-consuming feat of woodworking expertise involving white cedar ribs and planking and spruce gunwales; it was a melding of the design features demanded by laden travel over rock and rivers.

Cedar-canvas canoes had appeared in the 1870s but didn’t come into general use until after 1904. It was then that William and Harry Chestnut of Chestnut Canoes in Fredericton, New Brunswick, were granted the Canadian patent for that type of construction.

It was an important time in the history of canoeing. The evolution of the factory-produced canoe in those years from heavy ship-lapped planking to light cedar-canvas rescued wilderness travellers from much torturous work, a technology shift as liberating for the human spine as the introduction of Kevlar 80 years later.

Chestnut’s Prospector model, first produced in 1923, was so successful that the Geological Survey of Canada, with half a continent to survey, ordered 25 to 35 of them every year. It was built without a keel—unless specified by the customer—and was symmetrical—unless you wanted the V-stern version to have the option of using an outboard motor. It had moderate rocker compared to today’s more dedicated whitewater hulls, though in longer lengths the rocker become much more pronounced. It was available in a diversity that General Motors would appreciate; there were six different models from 16 to 18 feet in length.

After Chestnut, a profusion of Prospectors

For 55 years Chestnut stamped their name to the deck plates of Prospectors, right up until the company closed shop in 1978. In flattering gestures that the holders of the original Chestnut molds have not always appreciated, dozens of canoe makers hoping to gain both credibility and add a sure best-seller to their stock have since produced their own version of the design.

Hugh Stewart of Headwaters Canoes in Wakefield, Quebec, builds 15 to 18 canoes a year from traditional materials. Given that he actually owns two of the original Chestnut forms, and does extensive hard tripping in his own Prospectors, he has an authoritative take on the design.

“These boats are not to be thought of as Chippendale furniture,” he says, “They are tough, field-repairable working machines. Their primary characteristic is their great bow buoyancy under load.”

Rather than push water, the bow cuts it sharply and then, ideally just forward of the bow paddler’s knees, the hull flares gracefully at the waterline into its full width and volume to provide the buoyancy needed to carry the work gear of the past, and camping gear of today.

Despite its utilitarian genesis, it combines lines no barge operator would recognize. The upward slope of the gunwales at the bow and stern, the flaring hull shape and the slight tumblehome make for a symphony of curves for those with the eyes to see it.

An unmatched design for wilderness tripping

The original Chestnut Prospector forms have scattered across the continent and met various fates, though some of them, like Stewart’s, are still turning out “real” Prospectors. Many new molds turn out variations on the same design in all manner of materials.

So, it is up to the buyer, to the eyes of the beholder, to decide if their modern version of the Prospector is deserving of the name and comes close to the original 85-year-old idea.

You may decide you want a real card-carrying Prospector, one built from cedar sheeting and canvas in which you’ll go forth and seek your adventure. But if you do, caution your children sternly not to leave your legacy outside in the backyard after you pass on.

Brian Shields paddled his first Prospector at the age of 10, a story he recalled in “Bred in the Bone” [Canoeroots, Early Summer 2006].

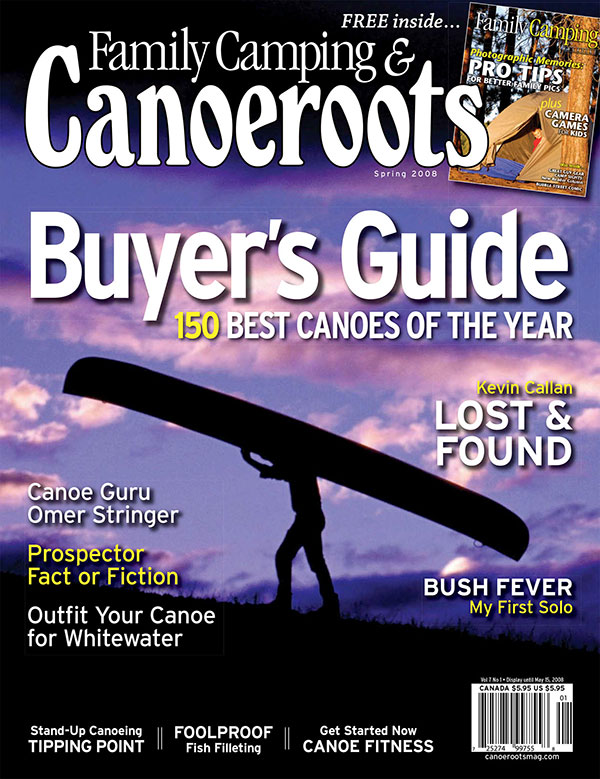

Even Prospectors have to rest. | Feature photo: Klaus Rossler

This article was first published in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.