Alchemy is the ancient science and philosophy of turning something base into something precious. This was the starting proposition guiding the writing of this column way back in 1999 and still is to this day. Longtime readers will recognize two themes occupying this space: risk and reward and the valuing of our rivers. Lately it has been more of the former and less of the latter. My pessimistic self senses paddlers today collectively value our rivers less than we did in the past and less than we should.

Where have all the conservationists gone?

There was a time when being a river runner meant being an environmentalist. Through the 1960s, 70s and 80s—the dam building heydays—many of the significant battles to protect rivers were led by river guides. Heck, the only people who even knew the existence of some of these rivers were paddlers. The only people who realized what was at stake were whitewater paddlers.

This isn’t the case anymore. With some notable exceptions—and not to downplay the disproportionately large role a few individuals play—river runners have all but disappeared from the river protection conversation.

The overwhelmingly good news story out of this is that now other people care. Lots of other people. Rivers, unlike pre-1990s, have legions of defenders. River protection used to be anti-development, counter-culture and on the fringes of society. It has now become mainstream, main street and second only to a more generic climate change in the average person’s understanding of the importance of the environment.

Changing coalition meets a new range of threats

Leading the new river protection movement are First Nations groups in Canada and Native Americans in the United States, people who have always cared but lacked a mechanism to state their concerns. Second are local citizens and landowner groups. There is also the greater public which has proven on occasion to mobilize around key environmental issues—river or otherwise.

What’s important here is the changing nature of the threats to our rivers. Big hydro-electric used to be the big problem. This is less so today, although micro-hydro still rears its ugly head in various regions every five or so years. Big dams are, well, big. Big environmental impacts, big dollars and with sensibilities, pretty straightforward to argue against.

More insidious are today’s threats: water quality degradation, ecological habitat destruction, water exports, withdrawals and ambivalent legislative protection that represent slow incremental and watershed-wide creep rather than the focused crisis of a dam project.

Consumers, not conservationists

At the take-out, I don’t hear many paddlers talking about what rising water temperatures will do to fish stocks or what acidification is doing to aquifers. At a very concrete level, these things won’t affect the shape of GoPro Wave or Big Huck Falls. Whitewater paddlers have become consumers of rivers rather than vested stakeholders.

Mountain bike groups and cross country ski clubs build the trails they recreate on. Fishing clubs sink money and manpower into restoring fish habitat. As paddlers we get our staggeringly amazing resource for free. Just because we don’t have to pay for it does not mean it is not worth anything.

Modern social media-centered paddling has turned rivers into nothing more than a series of features, with nothing in between them or connecting them. You may hear a paddler explain that there is really nothing between McCoy’s and The Lorne on the Ottawa River, or between Sunshine and Toilet Bowl on the Green River. The whole thing is a river.

Taking a holistic view

As paddlers we are pre-occupied with only the splashy bits, but that pales in comparison to the ecological and magical value of the whole headwaters-to-ocean thing. We need to recognize that what is upstream of the put-in and below the take-out is vitally important. We are getting a free ride on a precious resource. One that we are not so vocal about defending, short of a dam proposal.

So how do we move from consumer to steward? There are a few key groups at the provincial, state and national levels working hard. But more important is local ownership. We must stake a claim to a river we call home and make it our own, getting organized and contributing to caring for it, alongside other paddlers and other stake holders who share it with us.

Jeff Jackson is a professor at Algonquin College. Alchemy is a regular column in Rapid Magazine.

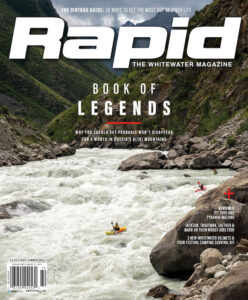

River conservationists, stake your claim before it’s too late. | Feature photo: Tegan Owens