The river expeditions of the second half of the 20th century were the founding of whitewater paddling as we know it today. Stocked with surplus military gear and emerging technologies, paddlers descended into treacherous and concealed river gorges. The only information known on the whitewater within their depths sourced from the accounts of local communities and what limited geographic knowledge existed. It was a time before Google Maps and stockpiles of GoPro footage flooded YouTube. When paddlers returned with tales of mysterious cataracts they proved runnable.

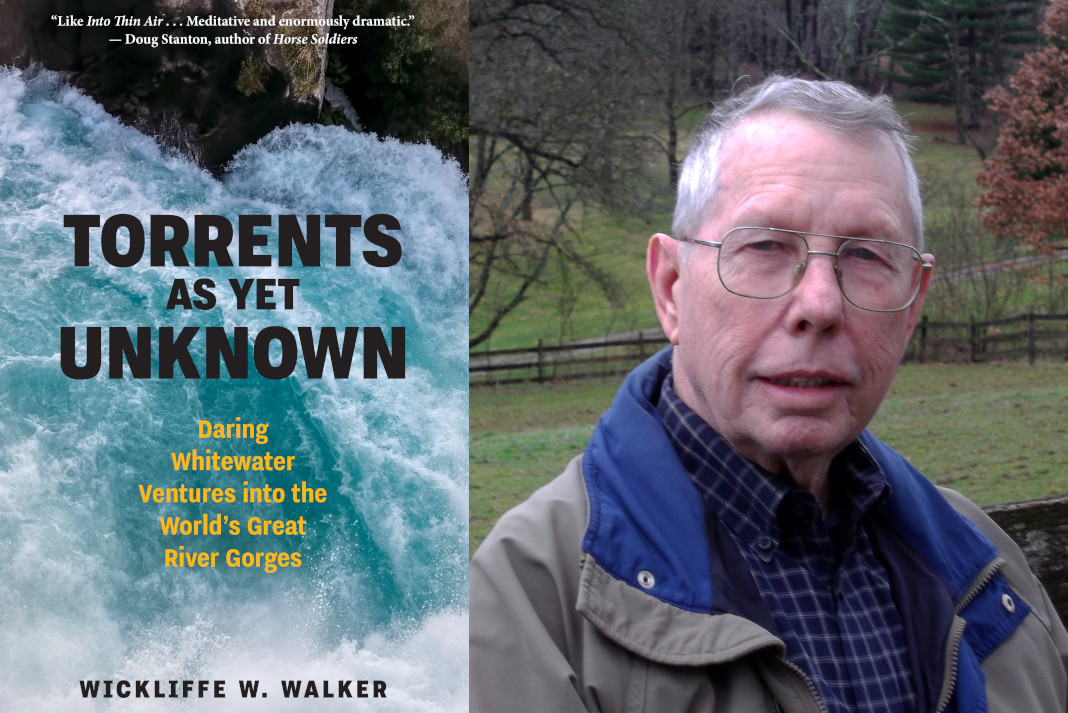

At 77, it is a volume of whitewater history Wickliffe (Wick) Walker has lived through and has himself largely contributed to. In his new book, Torrents As Yet Unknown, Walker guides us in narrative form through a collection of the most compelling ventures into river gorges around the globe over the course of this significant half-century. The reported stories are not of his own feats, but of fellow peers and icons of the day.

“The idea came to me that a lot of these stories from the 1950s through 2000 were very little known or were all distorted with campfire rumors,” says Walker. “I thought it would be an interesting project while there were still most of these people alive to track down and tell some of these stories.”

A Lifetime of Whitewater Tales

Walker found his path to whitewater the same way many have, through open canoeing in his youth. Through his adolescence and early adulthood, he forged his paddling prowess on the Potomac River alongside childhood friend Tom McEwan—another whitewater legend in his own regard. Walker went on to race canoe slalom at the highest level and represented the U.S. in C1 at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, the first to include whitewater.

Not long after competing in the Olympics, Walker’s taste for expedition paddling took shape close to home. Walker accompanied a party including McEwan to make the first known descent of the Great Falls of the Potomac River in 1975—a feat he and McEwan had dreamed of for years. Walker went on to take part in expeditions on rivers as far off as Bhutan and Pakistan. He also served a career as an officer in the Army, retiring as a lieutenant colonel after his work that included intelligence and special forces.

In 1998, Walker was a trip leader and served as ground support for the first American expedition into the Yarlung Tsangpo Gorge, accompanying paddlers Tom McEwan, Jamie McEwan, Roger Zbel and Doug Gordon—a superb class of their day. Tragically, Gordon lost his life during the attempted descent, bringing the team to exit the gorge, which Walker chronicled in depth in his 2000 book, Courting the Diamond Sow: A Whitewater Expedition on Tibet’s Forbidden River.

Walker is the author of two other titles, Paddling The Frontier: Guide to Pakistan’s Whitewater (1989) and Goat Game: Thirteen Tales from the Afghan Frontier (2013), collections of fiction stemming from Walker’s career in the military as well as his personal experience on the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Torrents As Yet Unknown

To write his new book, Torrents As Yet Unknown, Walker spent nearly a decade reporting on archived materials and traveling to interview many of the characters in the book. What Walker has compiled is an indispensable history of modern river running and the rivers that are now benchmarks in the sport—some even run commercially.

The 200 pages of Torrents feature 10 of these histories framed around specific expeditions. It begins with the film production that brought about the 1950s raft descent of the Indus River by Grand Canyon guide Don Hatch and company. The book also includes a decade of fantastical ventures by British kayaker Mike Jones, including the time he paddled down the flank of Mount Everest from the base of the Khumbu Glacier, as well as other tales like the endless Soviet-era road trip of the Polish team called the Canoandes, which culminated at what was once believed to be the world’s deepest canyon on Peru’s Colca River, and Doug Ammons’ solo first known descent of the Stikine River.

In the book’s final act, Walker revisits his team’s 1998 expedition to the Yarlung Tsangpo River, often called the Everest of rivers. The author shares the experience of his friends within the gorge, which would turn to a devastating conclusion.

With Torrents As Yet Uknown, Walker brings us to river level and captures the sensation of anticipation as we drift toward the rumbling around the next bend. Paddling Magazine caught up to discuss the book with the author and the wisdom of whitewater he has amassed in his lifetime.

An Interview With Wick Walker, Author of Torrents As Yet Unknown

Paddling Magazine: You’ve lived through the entire era written about. It’s something you grew up with as a kid coming up in paddling and paralleled your entire life. How did it feel for you, personally, to catch up with some of these paddlers—some your heroes, some your peers—and to have these conversations about these historic expeditions?

Wick Walker: That wound up being the most rewarding part of doing this whole project—traveling around and meeting some of these people and talking with them in depth. Some I had met in passing over the last 50 years. Some I knew only by reputation. But during that period most of us had been focused in our own silos, on our own expeditions. Sometimes keeping them deliberately secret from people. So the chance to travel around now and meet them and experience it through their eyes was the most remarkable and rewarding part of the project. I also like to think that although this certainly isn’t a memoir, that seeing it through my eyes and through my own experience provides kind of a unique viewpoint on all this.

PM: Which of the paddlers included in the book stood out as especially interesting characters?

Walker: There were such a variety of people as protagonists in these different stories. I think the individuals and their motives were so various. I never actually got a chance to interview the Chinese team members on Tiger Leaping Gorge. Happily, I got ahold of one of their diaries, but I wasn’t able to get out to China and track down anybody because the geopolitics just made that impossible before I could get to it. There were the motivations, almost suicidal motivations, of the Poles and the world’s longest road trip. And Doug Ammons is a case all by himself. I love his writing. I like Doug and there’s just nobody like him.

So I’d have to say each chapter I kind of selected because they were these interesting people.

Oh, and Mike Jones. If there was one that I had to pick off the top of the whole list, it’s probably Mike Jones, the Brit. He was a total adrenaline junkie, and he had this vision, kind of the British 19th-century exploration calling. He was out there doing things before anybody else and taking some huge risks—which eventually killed him. Jones was the only one where I couldn’t write a chapter about this one canyon, or this one group on these dates. I had to do the whole 10 years of Mike’s career to tell that story.

He deserves a book. Not by me. I wouldn’t be the perfect person to do it. But as far as I know, the two chapters about him in Torrents are the only beginning-to-end story of his paddling that’s ever been done. Everything else I found were magazine articles of verbal accounts and that sort of thing of one adventure or the other. As far as I know, I’m the only person who started with him as a beginner paddler on the Ian River and wound up in the Karakoram.

PM: There aren’t many photos in the book, but instead illustrations and maps for each chapter. It felt complementary to the narrative. Was it your intent to not use photography?

Walker: Aside from the economics of publishing a book with photos, which is much more expensive than publishing a book without, I also just feel like the sport, especially these days, is inundated with good-quality photography and video. All over YouTube and everywhere else. I didn’t know that I could contribute much to that. I’ve always liked pen and ink illustrations in expedition accounts. In 18th- and 19th-century expeditions artists went out as the recorders of the expedition and brought back wonderful illustrations that were expressive and gave you a sense of place. I liked that old-fashioned look and thought I did not want to be producing a coffee table book. I found Kim Abney, and I’m really happy with what we came out with as the overall visual appearance of the thing.

PM: You end the book with the Tsangpo expedition of the late 90s—a serious and tragic expedition that you were a part of. This felt like a moment closing the era you’ve captured in the book and the transition to the period of whitewater paddling where we are today. Would you agree with that?

Walker: I think the period of time I knew and was involved in was very much the early development days of the sport. And we were in some ways so lucky to be able to be inventing some of this stuff. That progress was in radical leaps and bounds from rubber World War II bridge pontoons to more specialized rafts. And from aluminum canoes to covered fiberglass and then rotomolded plastic. So we really were able to experiment with and make changes. Today it changes in inches.

The extreme boaters today are all doing these really wonderful things, but they’re maybe adding layers slowly to the sport. So it’s a different thing. I also think that in terms of expeditions, I cut off the book right at the point where a lot of things like satellite photography and satellite telephones really changed the expedition world and how you could prepare and scout.

PM: What’s held you to whitewater over the course of your lifetime?

Walker: Oh, I’m probably the last person to be able to describe that. But certainly, there were so many facets to it. I got into it through open canoeing in the Quebec wilderness and migrated to slalom racing at the upper levels. Then migrated to river running and expeditions, and then to writing about it. Each time I wore out my knees, broke something or got too old, there was some new aspect of paddling that emerged to me. And I think rivers are that way. I think there’s just so much dimension to moving water and how we relate to it.

PM: Is there an ultimate lesson river running has taught you?

Walker: Probably a sense of humility in relation to nature as a whole. You know touching the living planet and the humility that brings to you, but also the appreciation.

PM: What do you hope readers walk away with from Torrents As Yet Unknown?

Walker: I expect it’s going be different things for different people. I felt all along that I was writing for a couple of different audiences. I think the paddling community is going to take some interesting history, and appreciation of their sport, and maybe learn some lessons to use on the rivers. I’m also hoping it’s going to touch a broader audience of the outdoors and maybe the general reading public. To be honest, I have no idea what some of those people are going make of this. [Laughs.] I’ve gotten some very blank stares at times. So I’m looking forward to seeing what happens.

PM: What’s next? Do you have another book in the works?

Walker: Well, my wife has pointed out that my books have each been almost exactly 10 years apart, all four books. Going by that, my next would be in my late 80s. So she suggested I take up short stories.

Truthfully I want to continue writing. I don’t have another book like Torrents. Like everybody, I’ve got the half-finished novel in a drawer. But realistically, I’m looking forward to two things. One is some shorter work. The other is going back to something I’ve done a number of times in my continuing education and doing writers’ workshops here and there. I kind of gave up doing those when I got deeply involved in the book and had a deadline. But I want to get back to those. I find those fascinating.

Torrents As Yet Unknown is available today where books are sold.