Why do we do it? Why do we paddle remote rivers every summer, year after year? Why in February, when the snowdrifts still sit hard-edged in the backyard and the light comes charging back, do we river runners feel the unspoken dread of a summer without a river? The new light mixes memory and desire, tumbling old friends and rivers of the past in winter reveries. Paddling partners reach out to each other, questioning, proposing, easing each other’s fears of being left behind to tend some scorched and mundane bit of a garden in the oppressive summer heat.

Perhaps travelling rivers is an excuse to dream. The river I am thinking of this time is the Mouchalagane, last year’s antidote to urban boredom. By spring, after months of planning, we nickname it the “Mouchie”, a name well-suited to some pet that is always there to lift your spirit in the pewter-coloured days of late winter.

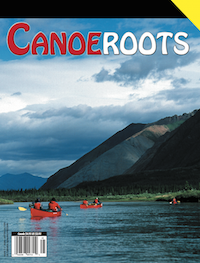

The Mouchalagane is a tiny blue line on the map. Beginning on the high, sparse plateau west of Labrador City, it falls southward only 130 kilometres, tumbling, rocky and narrow through most of its length. For a two-week trip the pace is languorous. Our only deadline is making a float- plane rendezvous on Manicouagan Reservoir—the flooded meteor crater at the end of the river.

The time available transforms the trip. It means that we rarely pass a breath-catching campsite without pitching the tents. And we only look at our watches to confirm why we’re hungry. A great deal of time is spent staring at the river, and this is seen as a perfectly normal pastime. We talk to each other and reveal the little secret things that we often keep hidden even from ourselves. Books are passed around through many hands and are mostly read as close to the river as possible, often well into the night. And the inconceivable happens: the ever-early risers often sleep late.

Maybe we escape to the wilds to play hunter-gatherer. With all our extra time, the fishermen in our small group pretend to be predators, endlessly wearing out the speck- led trout in a laughable game of catch and release. They often leave at first light, and working up or down through the limitless eddies, come back late for breakfast wearing satisfied cat-grins and carrying only their fish stories. Fishing lessons take place and soon everyone is playing the game. It seems only the fish are not having a good time.

Or it may be that we simply need to feel something different, to escape a life lived on claustrophobic acres of windless office carpeting in some highrise centre of power and influence. We enjoy marking the passing of the grey days with rain-fires, sheltered under a spark-ravaged wisp of a tarp, creating a rough comfort in the dampness and wind.

It is, we think sometimes, for the water that we drive for days and push the confines of credit limits to pay for floatplane charters. We are whitewater paddlers, and we travel in the company of fellow zealots, each infatuated with making the move, sacrificing the boats on the “Mouchie’s” rocky altar and scouting every wave of every set so that it can be played like a piece of music.

The Mouchie has numerous stretches of water rated beyond the limits of most open canoes. We run all the scary stuff for the camera and bounce out at the ends pumped with adrenaline. Spontaneous war cries leap out, euphoria finding a voice over the sound of moving water. Yes, this high could be the reason we do this.

Finally, there is a stretch of river that drives the boats to shore. The land falls away and the water begins to scream and consume itself. Like giddy children, we skip along the wide granite edge of its spring floodplain, picking flat rock campsites, and then again and again finding better places, as we laugh into the deep rock rooms hid- ing under immense overhanging slabs. The river noise fills us and the water tears past so fiercely that the mind will not allow the eyes to look even for fantasy lines out among the madness. The hypnotic river draws us to its edge, sits us down gently and sucks our minds dry. At a time like this, we don’t ask why we’re here. We know we’re about to camp in Heaven.

And it is for this reason that I am tempted to say it is the campsites. For when our bruised canoes are back on their racks, stored for another winter, and our memories of the Mouchie are aged and mellowed, it is the campsites that we seem to most remember. It is the rolling Amazon forest of caribou moss that we sleep on again in our reveries and it is our dramatic camp in front of the dark and comforting rock rooms on the river’s floodplain that is always the first retreat for the mind.

But isn’t it all these things and then some? The winter dreams, the languor of river time, the adrenaline of whitewater, the campsites—all of this makes the river something we turn to each year. We paddle because we have come to know that a remote river always asks us who we are, and given a canoe, always answers by trans- porting us so far beyond the bonds and the shackles of the ordinary. Our time spent together on the Mouchie is enough to sustain us for another year, until our hemi- sphere tilts back toward the sun, igniting the fire within us for another wild river.

Brian Shields is a retired sport-fishing guide who presently fritters away his life in his solo boat, trying to perfect his cross-forward stroke.