In May of 2003, three expert kayakers from Washington State embarked on a circumnavigation of Iceland. Leon Sommé and Shawna Franklin—BCU coaches and co-owners of the kayak school Body Boat Blade International—joined Chris Duff, also a BCU coach, sometime carpenter and one of the world’s foremost expedition paddlers well-known for his solo circumnavigation of New Zealand’s South Island in 2000.

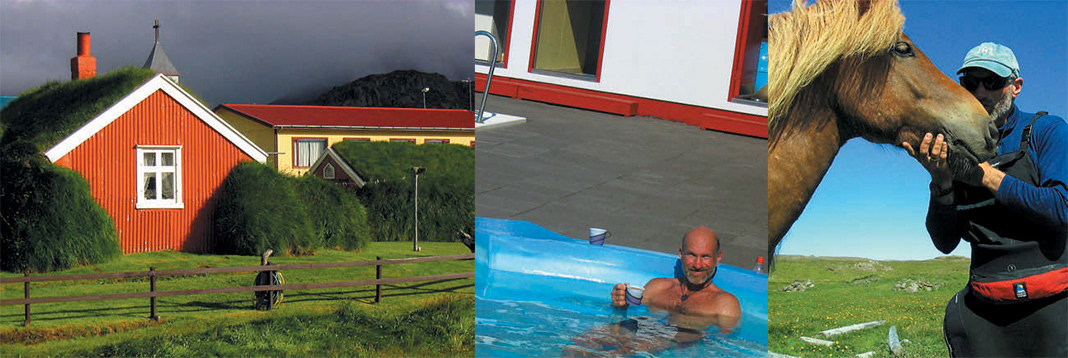

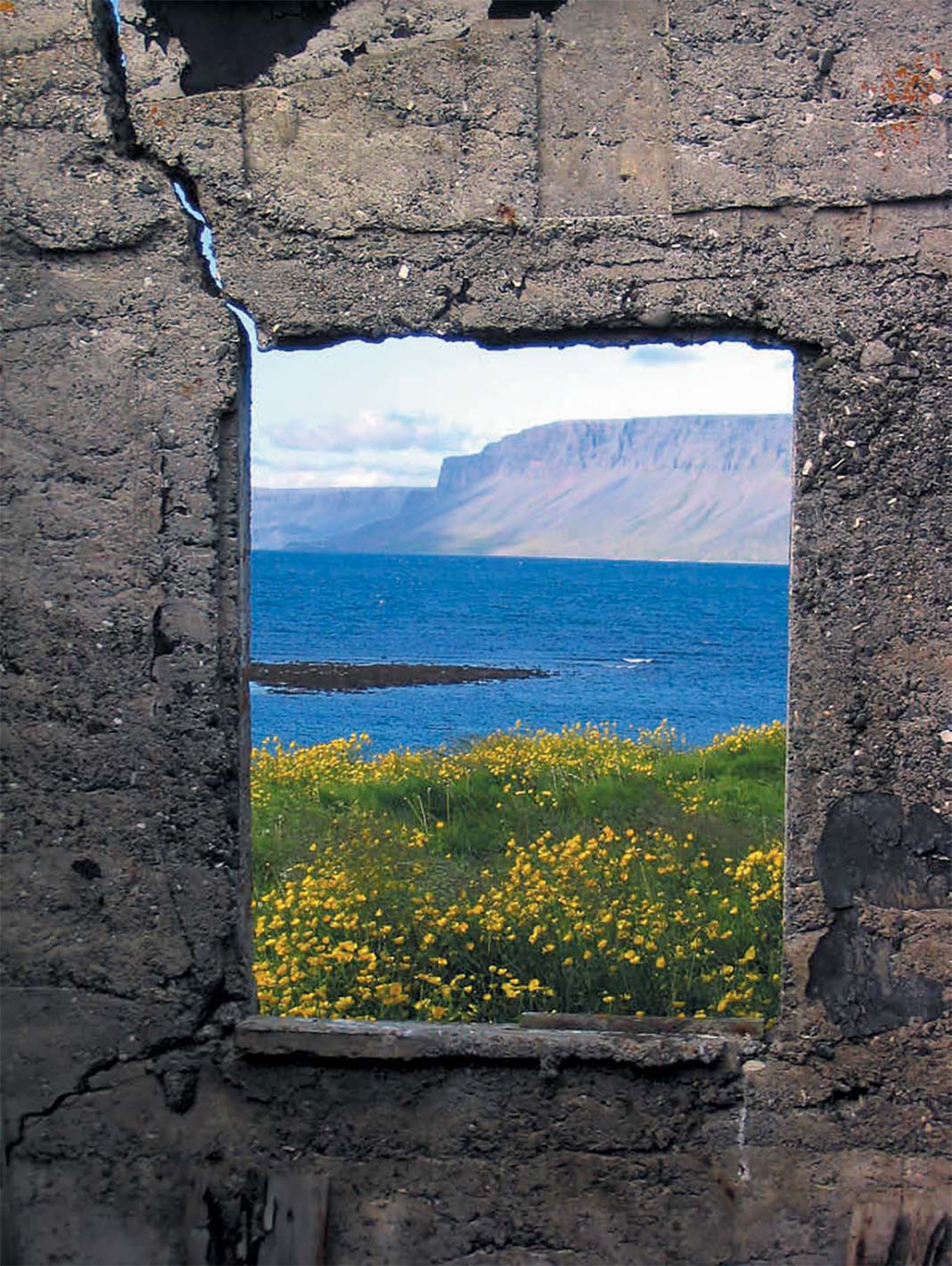

Iceland was first circumnavigated by Nigel Foster 25 years ago. Few paddlers have repeated the feat, partly because of the challenging weather—you have to put in long days on the water to get all the way around the 1,700 nautical miles (3,000 kilometres) in the short sub-Arctic summer. With the open North Atlantic on all sides and unpredictable weather, much of Iceland is challenging paddling.

The South Coast is undoubtedly the crux, presenting an unbroken expanse of windswept black sand beach and dumping surf. In storms, there is no place to hide from the wind, the rising seas can consume the beaches, and the nearest dry land is far away over impassable areas of glacial ponds and quicksand.

Beginning in the eastern town of Seydisfjordur and traveling clockwise, Leon, Shawna and Chris hit the South Coast at the beginning of their trip, where they paddled all day every day without pulling ashore until it was time to camp—to minimize the number of times they’d risk getting pummelled in the surf.

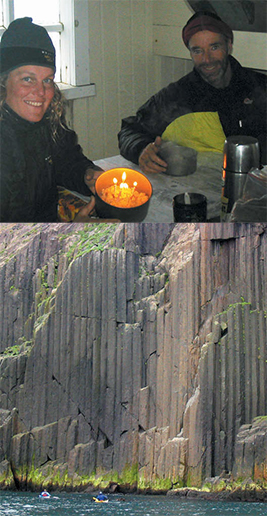

One night on the South Coast, a storm hit and the three had to seek shelter in one of the numerous well-stocked emergency shelters that dot the Iceland coast. From there they were evacuated to an inland town to wait out the storm, rest and re-supply.

“The Rescue” became the team’s harrowing adventure story that everybody hears first. But beyond the bleak South Coast, Leon, Chris and Shawna were charmed by what they describe as a “utopia in the North Atlantic”—a tidy land of hospitable people, free-running herds of domestic Icelandic horses, summer wildflowers and unlimited free camping. It’s a place where every little town has geothermal heated swimming pools and hot-tubs where friendly attendants serve you coffee while you soak away the aches of a three-month paddle.

The team successfully made it back around to Seydisfjordur in 81 days. Shawna became the first woman to paddle around Iceland.

Adventure Kayak magazine interviewed Leon Sommé to learn more about this remarkable trip.

An interview with Leon Sommé

Q. Wow, a 3,000 km, 81-day circumnavigation of Iceland is a pretty ambitious trip! What inspired you to take this on?

Well, it was essentially an email from Chris Duff. One day we just got an email that said, “Shawna and Leon, would you be interested in circumnavigating Iceland with me next year?”

Q. Ireland, Great Britain, New Zealand—Chris Duff is known for doing all these grand expeditions alone. Why did he decide to invite you and Shawna along on this one?

That’s a really interesting question. He had an incident on the New Zealand coast where he had to have a helicopter rescue and his boat got broken. And I think he just kind of saw his mortality on that trip and needed to get his mindset back to where he was comfortable being on the water again.

[Also], we live a very simple life like he does. We have a cabin that’s 12’ by 12’—144 square feet with a little loft. It’s heated by wood. Our lighting is candles. No running water, no electricity. And Chris lives in a 13’ by 13’ straw-bale house. Chris is a minimalist with what he carries in his boat and Shawna and I are considered minimalists by most people as well.Q. What happened during that storm on the South Coast that led to you having to be rescued?

The winds just kept increasing until they got to hurricane force and it was blowing that black sand which was just pelting our tents and burying our boats. And we literally had to come out of our tents every half an hour and push the wet sand off the tent and then shovel it away.

About one in the morning we decided the tents had to come down before they got destroyed, and we were going to attempt to get to the rescue hut on foot which meant crossing a glacial river. We dragged one of the boats over to the river and Chris [paddled] and Shawna and I hung onto the end toggles. We got to the other side and then continued walking to the hut which was probably only two kilometres from where our tent was.

It took us from one in the morning until six in the morning to actually make that all happen. We couldn’t see anything. You could hardly breathe. When we finally went back and recovered things, all the gel coat shine on the boats had been sandblasted off. Shawna’s helmet was sandblasted from a blue [colour] to black.

Q. So you got to the rescue hut and out of the storm. Why did you decide to call for help?

The storm was getting stronger, the rescue hut was actually shaking, being battered by the wind. So we called [by VHF radio] to notify people that we were there and that we may need help. A helicopter from Reykjavik happened to be out and picked up our broadcast, and they called the local rescue team in Kirkjubaeklaustur, the closest town. Later that day they made their way out to us because we didn’t have very much water left, and we didn’t have very much food with us [at the shelter] by the time we got there.

Q. That was a very bad day, because earlier you actually flipped and came out of your kayak while paddling in the rough seas. What happened?

That morning that we set out the barometer had actually dropped quite a bit, but the winds for the most part were at our backs, so we were just trying to take advantage of those. And Chris’ pace was much quicker than ours, so we were separated from each other on the water and not in communication.

When things started getting nasty we were still in hopes of reconnecting with Chris that day, so we stayed out maybe longer than we should have, but it was still conditions we could paddle. It just happened to be one of those times where as much as you rely on and trust your roll to be there forever, it just didn’t work out. So all of our other training came into hand and it was very lucky we had it.

Iceland Expeditions by Numbers

1,700 | Iceland’s circumference in nautical miles (3,000 km)

400 | approximate number of Iceland Expeditions 2003 T-shirts sold to cover trip expenses.

81 | days on trip.

59 | days paddling.

25 | length of a typical paddling day, in nautical miles (45 km)

120 | longest stretch between coastal towns, in nautical miles (from Hofn to Vik on the South Coast).

6-8 | number of days’ food supply typically carried.

20 | number of days spent paddling the South Coast, with no stops between campsites.

8 | usual number of hours spent on the water each day.

11 | number of equipment sponsors.

5 | total number of months away from home.

400 | number of Snickers bars consumed.

14 | number of pounds lost be each expedition member.

270,000 | population of Iceland.

60 | percentage of Icelanders who live in greater Reykjavik.

1996 | the last year a polar bear drifted to Iceland from Greenland on floating ice.

15,000 | number of miles Chris Duff has traveled by sea kayak since 1983.

2 | approximate distance in miles to the Arctic Circle from Iceland’s northernmost point.

Q. Being so far north and so exposed, Iceland is a pretty extreme trip. Is there anywhere in North America where you’d find comparable paddling conditions?

[Circumnavigating] Vancouver [Island] definitely wasn’t as demanding. There are many more outs. It would be hard to say. Maybe a good section of the West Coast of North America that included California, Oregon and Pacific Northwest coasts in a season like the spring, fall or winter to have the weather exposure.Q. You really trusted your lives to your kayaks. What kind of kayaks did you bring and why did you choose them?

All three of us had Nigel Dennis Explorers. It’s a great expedition boat. It’s fast enough and yet manoeuvrable enough to turn around and get out of a situation you might not want to be in. We also didn’t have skegs or rudders so we wanted a boat that handles nice without those mechanical features.

Q. You said you encountered high winds and a lot of following seas, but you didn’t even have skegs on your boats? Why not?

Mechanical things tend to break down and they don’t work very well on trips like that. A skeg when you’re going out through surf tends to be the last thing to leave the beach. It gets jammed with rocks. On my Vancouver [Island] trip I did a good portion of that solo and I literally had to get out of my boat once I was off the coast and free up the rocks because it was a very skeg-dependent boat, and that’s a very unnerving feeling sitting out in the Pacific cleaning rocks out of a skeg box so you can use it.

So after that trip I decided to go with boats that don’t need them. The Explorer is pretty good at that. There were days when I would have loved to be able to drop a skeg but, well, we were fine without it. There are strokes you can use—and holding your boat on edge—that help counter those conditions.

Q. Black is a pretty unusual colour for a kayak! People usually think about getting brightly coloured boats for safety. Why did you choose black boats?

Mainly just because all-black boats are a really cool-looking boat. Shawna and I both decided by the end of the trip that black boats in that environment were too depressing and it would have been nice to have brighter-coloured boats.

This is a report that I’ve heard from the U.K.: The coast guard looked at different boat colours and tried to determine which ones were most visible. And I believe that robin’s egg blue—which is the color of the U.N. peacekeeping helmets—was one of the the most visible, yellow was the second most visible and black-on-black was the third most visible.

Q. You were several months away from home on a self-supported kayak expedition in a foreign country. What was the most difficult part of this expedition to plan?

Arranging to have the gear from the sponsors and writing them letters. The rest of it’s all fun! I think all three of us have decided that if we do another big trip, we probably won’t seek so much sponsorship. Expeditions should really be planned on the back of a napkin, sitting in a bar.

Q. Paddling eight or more hours per day, almost every day, what did you eat to stoke the furnace?

Essentially our breakfast every morning was oatmeal with cut-up apples, raisins, sugar and butter. And every evening it was some sort of pasta. [For lunch,] peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, boiled eggs and big chunks of cheese. We threw butter in the pasta as well. Butter went into everything, for the calories. All of us lost I think 14 pounds pretty much by the time we got to Reykjavik. We ate 400 Snickers bars so we were just constantly cramming food in our face.

Q. You had a pretty grueling schedule to get around Iceland during the summer weather window. Didn’t you get tired of paddling all day every day?

At the end of that trip it was sad to think that we weren’t going to be able to just keep doing that. It’s not only just being on the water and paddling. On a trip like this you just set out in the morning knowing you’re going to see something you’ve never seen before. And Iceland is incredible so I think on every single day of that trip at some point I’d just stop and look around me and out loud go, “Wow, this is incredible!”

Q. On a long trip you have a lot of time to meditate. What’s the life lesson of a trip like this?

Being exposed to how beautiful the natural world is and giving you a greater appreciation for that, and hopefully making your life so that you live a life that helps support the beauty of the natural world and survival. You realize you don’t need very much “stuff” to survive. You need a pot to cook in, a source of fuel and—actually you don’t even need that!

Q. What would you say to someone considering doing an expedition themselves?

Don’t wait until you have enough money. Don’t wait until your kids grow up, until you graduate high school, whatever. If an opportunity like this steps into your lap, take it. Things like this you can’t pass up in your life. It’s too important. It has too great of an impact on who you are to let it go by.

Leon’s top five FAQs

5. What language do Icelanders speak?

They speak Icelandic. It’s really a very hard language to speak. But luckily close to everybody in Iceland over a certain age speaks really good English.

4. How cold was it?

A lot of people think Iceland is really “icy” and very cold. But for us on the [North American] West Coast it’s a lot like our spring and fall. It was 40s to 60s oftentimes and sometimes really nice days in the 70s.

3. How did you get five months off work to go paddling?

People are always asking us how we get the time off. And for both Shawna and I it’s just how we arrange our lives and live our lives, not to have so many bills and things that we have to pay for.

2. Did you have land support?

No. We were completely self-supported.

1. How did you go to the bathroom on the water?

I have to release the spray deck and unzip my relief zipper and then I have a pee bottle in the boat. If it’s not too rough I can usually do that on my own, but when Shawna has to go we have to raft up. She has a big relief zipper in the back which is much more difficult and she actually has to be on her feet squatting over the edge. When it’s rough it’s very unpleasant.