For as long as he can remember, Robert Lester has been fascinated by water. As a child growing up in Butte, Montana, Lester would make miniature wooden boats and float them in waters feeding the mighty Columbia River. From an early age, he says he was fascinated by the “connectivity of rivers.”

At the end of each summer, Lester would concede his boat to the currents.

“I loved the idea that my little wooden boat could travel down the river to the ocean,” says Lester, 26, a professional skier, mountaineer and adventurer. “I decided then that I wanted to make the same journey. The name didn’t exist yet, but the Columbia River Canoe Project dream had been conceived.”

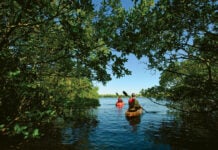

Paddle to the sea

Lester’s dream was cultivated by hours spent studying western watersheds on Google Earth. It finally became a reality last May, when he and 19-year-old trip mate Braxton Mitchell launched their canoe on Silver Bow Creek in Butte and set off on a 1,300-mile journey to the Pacific Ocean.

“If I was going to make this expedition happen, I wanted to have the greatest positive impact I could,” Lester says. “I set the goal to use the expedition to inspire stakeholders near and far to empower measurable improvements for the Columbia River’s ecosystem and its future.”

Ultimately, Lester wanted to share the wonders he discovered as a youngster: to reveal how the Columbia forms a watery ribbon draining over 250,000 square miles of western North America, connecting people and ecosystems and tying the landscape together across seven American states and one Canadian province. But he didn’t shy away from a harsh reality: 19 hydroelectric dams on the Columbia have radically altered its flow.

“Raising awareness and making environmental improvements will not be complete until the Columbia Watershed is as wild and free-flowing as possible,” notes Lester.

Highlights of the trip included “the pure beauty we saw and the connection with nature we were able to develop after so much time outdoors in the natural world,” Lester says.

Of course, spectacular scenery was tempered by physical challenges, including a one-day, 24-mile portage. Lester and Mitchell portaged a whopping 175 miles along the entire journey. Lester says the expedition was most remarkable for the way it created a relationship between himself, Mitchell and the water, in making the first documented source-to-sea descent of the Columbia starting in its eastern headwaters.

“We lived on this river for 52 days,” he says. “For that time it was truly my entire life.”

Lester also hoped to better appreciate the connection local Indigenous communities still have with the Columbia Watershed. Immersing himself in the river was the perfect opportunity to begin to understand this relationship.

“There is an implication in some modern teaching that Native American culture is extinct or irreparably damaged,” he says. “This is not the case. While it has undoubtedly been damaged, the spiritual and cultural relationship that Indigenous people have with the land and water persists. This relationship needs to be encouraged and promoted. In addition, the value all people can derive by learning from the connection between Indigenous people and land and water cannot be understated.”

“Salish-speaking tribes lived off most of the land we traveled through sustainably for over 30,000 years,” he adds. “Modern society can learn a great deal about future sustainability from past practices. This level of sustainability is what society should strive toward.”

Playing in streams and rivers as a kid reinforced the messages Lester heard in school: water is the basis of life on Earth. But in the end, paddling 1,300 miles to the Pacific Ocean taught him an equally important fact, which will be central to a documentary film about the journey set to launch this fall.

“Human life centers around water bodies and waterways,” Lester says. “Indigenous people relied on waterways for hydration, food and transportation. Modern society still relies on waterways in the same ways—yet most people do not realize this importance.”

Feature photo: Jonathan Stone // @jonathanstone_