The storm blew relentlessly, transforming the southern ocean into a heaving sea of mercury. An endless procession of waves appeared on one horizon and vanished on the other, their tops blown sideways into a stinging spray by the howling wind. Amidst the tyranny of the ocean Andrew McAuley’s touring kayak struggled to hold its own.

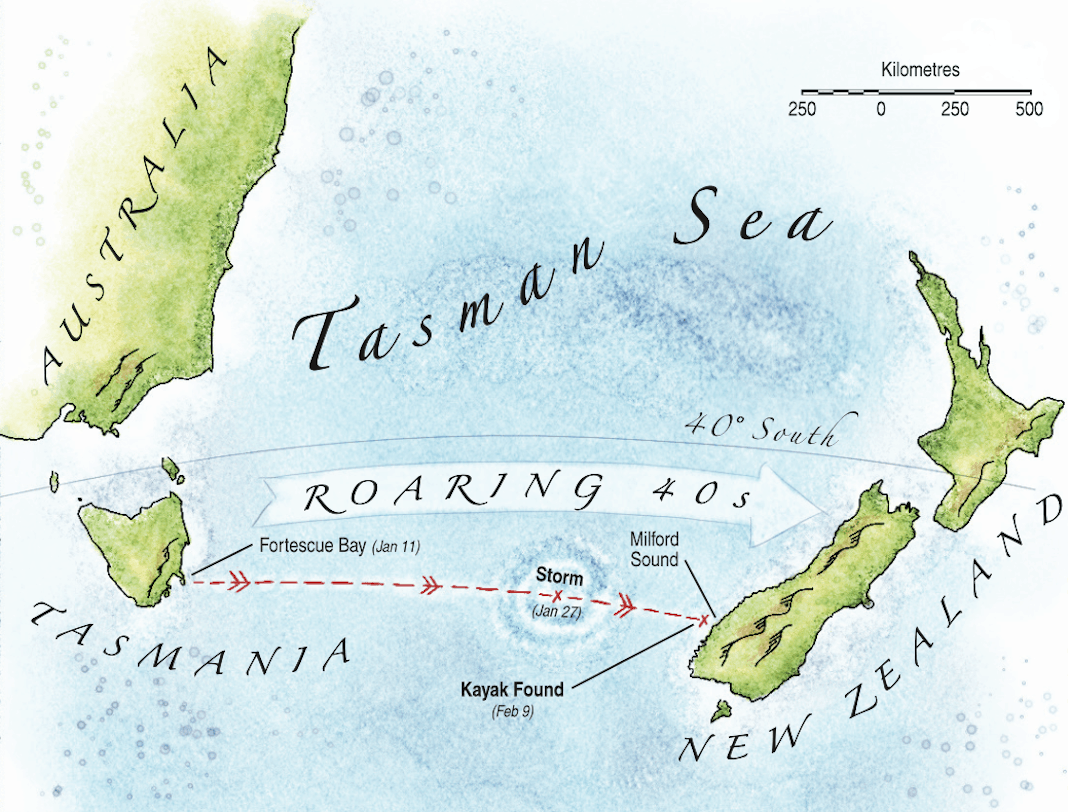

Inside the kayak, McAuley fought his own battle to stay calm. One night at the end of January, 2007, two-thirds through a 1,600-kilometre (1,000-mile) open ocean crossing between the east coast of Tasmania and New Zealand’s South Island, McAuley entered the 28th hour locked up in his kayak as the storm raged.

Many days later, with the nightmare storm behind him, the seas relatively calm, and the mountaintops of New Zealand’s southern Alps close enough to see on the horizon, McAuley disappeared. His family, friends and the worldwide paddling community were left with a mystery. Why did such an experienced paddler, so close to the finish of such a difficult journey, allow himself to be caught off guard? What could have happened?

Andrew McAuley disappears on sea kayak trip

McAuley made no false pretences about what motivated him to cross the Tasman sea alone in a conventional touring kayak. It was an adventure for adventure’s sake, a response to a deeply felt inner voice. He told ABC radio before the journey:

“I guess I’m really drawn to a journey like this—it’s a real personal challenge. There’s a great deal of satisfaction in coming up with an adventure that’s unlikely and improbable.”

The crossing was not a frivolous notion; only two previous attempts had been made, both by New Zealander Paul Caffyn, both unsuccessful.

McAuley spent nearly 10 years preparing for the trip. He completed three crossings from Australia to Tasmania via the notorious Bass Strait, as well as a solo, seven-day traverse of Australia’s treacherous Gulf of Carpentaria, earning him Australian Geographic’s 2005 Adventurer of the Year Award. On the surface, McAuley, a 39-year-old IT consultant from suburban Sydney, seemed an unlikely candidate for the award. Scratch deeper, however, and you would find a determined and diversified adventurer. Prior to catching the kayaking bug on a late-1990s trip in the Chilean fjords, McAuley devoted his considerable energies to mountaineering, making first ascents in Pakistan, Patagonia and Australia.

An inherently dangerous crossing

McAuley was not without his critics. Tasmanian police and Australia’s search and rescue service cautioned against the trip. Said an AusSAR spokesperson: “We had strongly advised against the trip to start with because we believed it was inherently dangerous.” Authorities went so far as to test McAuley’s equipment, capsizing his kayak and assessing its self-righting properties; they ultimately concluded that the boat was seaworthy.

The vessel was a standard touring kayak, a 19-foot Mirage, modified for sleeping inside the cockpit. A yellow fibreglass canopy carried on the back deck—whimsically painted with a cartoon face and nicknamed “Casper”—could be clamped down onto the cockpit for sleeping, providing self-righting capability and protection from the roughest storms. A yacht ventilator atop the canopy breathed when upright and kept water out when submerged.

The fact that McAuley was permitted on the water at all speaks volumes of his preparedness. Paul Caffyn’s late-’80s attempt was summarily prohibited before his kayak even touched Australian waters. Well aware of his critics, McAuley told the Sydney Morning Herald, “When you do [a trip like this], you are exposing yourself to criticism. I take risks, but they are calculated risks, and I want to be beyond criticism.”

McAuley’s January departure from Tasmania was his second attempt. He set out in December but turned back after just 48 hours when he found his sleeping arrangement to be too cold. “Responsible adventure is character-building and good for people, but I felt that to continue on this occasion was not on,” McAuley wrote on his blog. “Without wanting to sound too melodramatic…making the right decisions in situations like this can save your life.” After some modifications, he launched a second time.

McAuley’s chilling last words

Andrew McAuley’s entire route travelled below the 40th parallel, the heart of the Roaring Forties feared by sailors for its treacherous weather and unforgiving storms. Two-thirds into his voyage, McAuley endured a 40-knot gale that knocked out his spare satellite phone and tracking beacon. The conditions were possibly the worst experienced in the region since the storm that decimated the 1998 Sydney to Hobart regatta, sinking five yachts and killing six crewmen.

Enclosed in the cockpit as the kayak plunged nine metres (30 feet) between waves, McAuley had already endured two stomach-churning barrel rolls. The sea anchor he deployed at the approach of the storm kept the kayak’s bow into the weather most of the time, but in seas this large, even this was not always effective. For a third time, the kayak slid up the face of a monstrous wave, perched perilously on edge, then inverted and slowly righted once more.

He survived the storm and travelled several hundred more kilometres to within sight of his destination. On Thursday, February 8, with only 120 kilometres (100 miles) to go, he sent a triumphant text message to his wife, Vicki, and 3-year-old son, Finlay, who were already waiting in New Zealand: “See you 9 a.m. Sunday!” The weather forecast promised a benign end to a harrowing journey.

Vicki and Finlay gathered with friends and family in Milford Sound to celebrate. The legendary sea kayaker Paul Caffyn would be there in person to congratulate the man who accomplished what he’d failed to do. Caffyn told ABC radio, “We were planning to paddle out…and wait there until Andrew came in…with a bottle of whisky and ginger beer.”

At 7 p.m. on Friday, February 9, New Zealand Coast Guard received a scrambled, unintelligible radio call. McAuley’s family suspected the radio message was a hoax, or perhaps an attempt by Andrew to make his nightly check-in by radio now that his sat phone batteries were dead. A small search was launched, but nobody really believed McAuley could be in trouble.

By Saturday morning, analysis of the radio message deciphered some chilling words. Among them: “help” and “sinking.” A full-scale search began. Planes combed 25,000 square kilometres of wind-tossed ocean. On Saturday night, Rescue Coordination Centre New Zealand found McAuley’s upturned kayak in near-perfect condition just 54 kilometres (34 miles) offshore of Milford Sound. It was missing only the cockpit canopy. The paddle, satellite phone, GPS, and emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB)—not activated—were all in working order inside the kayak.

On Monday, February 12, after three days of waiting and hoping to find McAuley alive, the search was called off.

Speculation on Andrew McAuley’s fate

Paul Hewitson of Mirage Kayaks, the boat’s designer and builder, inspected the kayak and some of the retrieved video footage. His best guess about what happened: McAuley capsized while the cockpit cover was not in place and was unable to get back in his kayak. Then, somehow, paddler and kayak became separated.

McAuley had reported capsizing twice before and described the re-entry procedure as “gnarly,” complicated by the cockpit cover, video camera and other gear mounted on the deck. He hoped not to capsize again.An oversized cockpit and lack of a standard seat made it impossible to roll. Removing the seat was a necessary modification for sleeping and for accessing gear. Andrew sat on a beanbag, which doubled as a pillow, and retrieved gear in the rear compartment by lying down and rolling onto his stomach, using strings to pull his gear forward through a hatch in the bulkhead.

Hewitson guessed that McAuley was probably getting tired and, with the mountains in sight, would be eager to reach land. He may have pushed too hard. When a small cold front came through, he possibly didn’t think it necessary to put on his drysuit—which he’d planned to put on anytime there was rough weather—and would have been reluctant to trade making the miles for holing up beneath the canopy. Sadly, disaster has a proven habit of striking those who have almost reached safety—nearly all mountaineering tragedies occur on the return from the peak, when muscles burn and concentration is narrowly focused on the goal.

After the capsize, McAuley may have unscrewed the rear hatch to access his VHF radio and drysuit. Perhaps while struggling into the drysuit, he got separated from his kayak and, with it, the EPIRB. Some have wondered why he didn’t trigger the EPIRB right away.

“Andrew thinks the same as I do on this subject,” writes Tasmanian kayaker Laurie Ford on his website. “[The EPIRB] is a last resort. It is far better (if possible) to make contact by phone or radio and let people know the exact situation—rather than the huge panic and search that an EPIRB generates. Having said that, I’m quite sure that he would have intended to set it off (as I would) once he was in the drysuit. It was the separation from the kayak that brought him undone.”

Courage or selfishness?

Unfortunately, McAuley had overlooked the critical detail of attaching the EPIRB to himself, not the boat. Ford also speculates that if McAuley had carried a strobe light, he might have been spotted by rescuers on the first night of the search.

In his final days, McAuley conceded he may have miscalculated and pushed the boundaries too far. A self-portrait taken near the end of his journey bears scant resemblance to the confident, athletic face that appears in other photographs. His eyes are wild, cheeks drawn under a ghostly sheen of zinc oxide. At a memorial service held under grey skies at Sydney’s Macquarie Lighthouse, on a high cliff overlooking the Tasman, 400 friends, family and members of the kayaking and mountaineering communities listened to a haunting message recovered from McAuley’s kayak where he admitted, “I may have bitten off more than I can chew.”

“This really is extreme,” he said. “It’s full on. I really could die.”

But if Andrew McAuley had his doubts, his family does not. In the face of the inevitable public criticism about the perceived selfishness or stupidity of extreme adventuring, Vicki McAuley stresses that it was Andrew’s drive to explore his limits that made him who he was. On his website she posted a quote from André Gide that sums up the spirit of adventure so integral to Andrew’s life and the sport he loved: “Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

We can only speculate what may have happened to McAuley. | Feature photo: courtesy Vicki McAuley

I watched the documentary about Andrew. As a kayaker myself, I was compelled to watch and learn. As a father and a husband, i found Andrew’s desire to achieve this goal incredibly selfish. I stopped doing dangerous adventures when i became a father. The unforgettable image of Andrew’s little boy crying in the back ground and Andrew crying in the scene. Andrew was willing to turn around because the cockpit was to cold but unwilling to turn around for the sake of his wife and son. Personally he became drunk with his desire for adventure and showed real poor judgement. Imho

I share all this sea paddling love but security is a must, boundaries should not be trespassed.

Another one in the same tribe from Spain

Jose Juan

Thanks Virginia for this excellent accident analysis and providing us the opportunity to learn from others’ mistakes. There’s a lot to unpack in this article – it’s a perfect example of Raffan’s “lemons” theory of disaster. One last question: there is no mention of whether he was wearing his PFD or not. It appears not if he was trying to don his drysuit after a capsize and also if he sank. I feel for his wife and young son.

No PFD.

God Bless His Soul and to his Family!!! Andrew McAuley was a Brave Person to Cross the Tasman Sea!! Don’t forget their danger in Every thing we do!!! Brent Gordon Windsor Ont. Canada.

Again the word “tragedy” is used inappropriately. A tragedy is when an innocent person is killed thru no fault of their own, like a small child dying in a house fire or being run over by a school bus. When an adventurist dies doing something super dangerous for no reason other than self-indulgence or thrills it is not a tragedy. Sad for his family of course, but for any other observer it is at most an unfortunate outcome of a misadventure. Too bad, so sad.

Hi Virginia,

Re Andrew being unable to roll the kayak: it wasn’t the cockpit size or the non-standard seat that impeded his rolling the boat.

Being unable to roll the kayak was due to the “Casper” cockpit cover sitting on its arms on the rear deck and NOT clamping and sealing onto a dummy cockpit coaming to stop water filling the cover in a capsize. If Andrew had such a rear deck fitting, a full capsize may not have happened and Andrew would’ve retained that very best primary self rescue method: the roll. Most likely a recovery from a capsize with a buoyant air-filled Casper on the rear deck would’ve been quick and simple and not an out-of-boat ordeal in cold water.

The concept of the Casper cover for the crossing was brilliant but perhaps some details of the structure were flawed.

All so very sad.

Good analysis, it looks like he didn’t run enough worst case scenarios in the pool during the design phase. Also lacking personal on-the-body survival and signalling gear.

Thank you very much for an informative, thoroughly entertaining and insightful article.

I am an adventurer also, but NOTHING at all akin to the protagonist of your piece; indeed, it’s almost a laugh to include myself in the same note to you.

Thanks again, and all the best,

Jack Lyons,

kayak nut, ski nut, verrry slow cyclist, and world’s leading authority on all subjects (yeah, right….)

The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it. Michelangelo Buonarroti