There are magical places in this world where nature’s balance continues to unfold in stubborn defiance of the efforts of humans to tame the Earth. These places, like the sacred hidden Buddhist valleys near Mount Kailas in Tibet, can only be discovered and entered with the right attitude: an open mind and a reverence for wildlife in its natural condition. One such place is Peninsula Valdes—a provincial reserve on the Atlantic Coast of Argentina. This is the essence of coastal Patagonia.

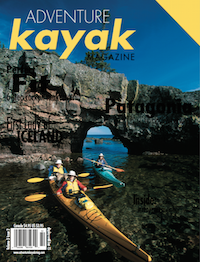

Pure Patagonia: Touring Argentina’s seldom-paddled coast

The Patagonian experience

I first visited mysterious Patagonia nearly ten years ago. Running away from a university degree of questionable value, I traded in my life savings for a camera, a backpack, and a plane ticket to Santiago, Chile. At that time, both Chile and Argentina were expensive for folks with thin wallets, and my experience in these countries was limited to a “get in, get out quick” sojourn to southern Chile’s Torres del Paine National Park. After a month in these countries, I beat a hasty retreat, my dineros severely depleted. But my curiosity about the land called Patagonia was even more intense than before.

A seed of burgeoning wonder was planted in my psyche by this land of soaring Andean condors and needle-like granite spires, all on a backdrop of endless blue-white icecap. Popularized by the logo of a certain outdoor clothing company, this jagged skyline is, however, but a tiny fraction of Patagonia. Patagonia proper is a vaguely defined geographical entity that encompasses all lands from roughly 40° south to the southern tip of Cape Horn, from the height of the Andean Cordillera to both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

Last fall, my partner Kelly Comishin and I had the opportunity to return to Patagonia to search for its true essence. Just married in September, we were on a working honeymoon, guiding sea kayak and hiking expeditions for Canmore, Alberta-based Whitney & Smith Legendary Expeditions. We were to discover a vastly different face of this rugged and intriguing area.

In the early 1990s, Steve Smith and Jane Whitney, then guides for another adventure travel company, came to Peninsula Valdes to look for new areas to explore. Armed with a road map, two single collapsible Klepper kayaks and ample food, the couple spent six weeks circumnavigating the Peninsula.

“I’m not sure what we were thinking,” claimed Steve with a trademark grin. “The outer coast is as wild as it gets—huge tide rips, reefs, and the coast is mostly cliff. What beaches there are are literally covered with sea lions and elephant seals—most nights we literally had to elbow our way through the wall of elephant seals on the beach and pitch our tents on a tiny platform.”

After six weeks of wind, cliffs, and 4,000-kilo elephant seals actually coming into their tent, Jane and Steve made it back to Puerto Madryn, the nearest city, and hunted down a nautical chart of the Peninsula. The incredulous proprietor of the marine supply store thought, as most would, that this was a backward way of doing things and, after hearing what the couple had done, respectfully handed them the chart, free of charge.

“In a way, we’re lucky we got the chart after the trip,” Steve said while looking at the jumble of reef, cliff, and tide rip symbols crowding the outer coast on the chart, “or we probably wouldn’t have even done it!”

After several years of working closely with the assistant director of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism for the province of Chubut, the couple were granted permission to run a limited number of kayak trips on the Peninsula—with a few strict limitations. Steve and Jane, both trained wildlife biologists, would lead expeditions with a small number of “field assistants” whose job it would be to do wildlife counts and note any different or interesting behaviours or occurrences. An official report, in Spanish, would be produced every year to provide a baseline count of wildlife populations in the Gulf. Officials would check in on the group every few days, watching the group from a boat offshore or hiking in to meet them at some of the more accessible beaches to ensure that no wildlife populations were being disturbed and that no-trace tourism was, in fact, the practice.

The assistant director loved what he saw. And so, ten years later, here we were. Steve and I were the project’s official biologists, and eight field assistants from all over Canada and the States were there for the Patagonian experience and to help with the counts.

Into the script of a wildlife special

After a brief whirl through the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires, we flew two hours South to Trelew—a town known for its Welsh history. This was our first introduction to the many similarities between Argentina and Canada. Both are immense, mostly empty countries—entire Argentine provinces have less than one person per square kilometre. In both countries one also finds folks who are intensely proud of their country, but who are from somewhere else. A visit to any Argentine supermercado will reveal the mostly European background of the people who immigrated to the country to settle its empty quarters. Fresh pastas and other Italian delights, Welsh cakes, French baguettes, and entire aisles of incredible wine fill the groceries.

From Trelew we drove a hired vehicle through Puerto Madryn out to our put-in near the tip of Punto Buenos Aires—the eastern claw of the crab pincher shape of Gulfo San José. From our camp that night, we watched in awe as a steady 20-knot wind blew against the outgoing tide, whipping up towering standing waves in the mouth of the channel.

If you want to see Patagonia, “sit still, and it will all blow past you.” –George Gaylord Simpson. There is only one rule that shapes the winds that brush Patagonian shores—they can come at any force from any direction at any time, and most likely form the direction you intend to travel.

We spread all our gear out on the pebble beach and proceeded to stuff 10 days of food into our boats—an ominous first-day task that all sea kayak guides dread, but that always ends up being easier than it first appears. What little agua dulce (fresh water) there is on Peninsula Valdes’ xeriscape is extremely alkaline, which means that we had to carry enough water for 12 people for ten days—over 200 litres in total.

Finally, 20 litres of water wedged between legs in every cockpit, we launched our laden boats and paddled east into a stiff Gulfo San José headwind.

Author George Gaylord Simpson states in his classic Attending Marvels—a Patagonian Journal that if you want to see all of Patagonia, simply “sit still, and it will all blow past you.”

There is only one rule that shapes the winds that brush Patagonian shores—they can come at any force from any direction at any time, and most likely from the direction you intend to travel. Thus, a pleasant onshore breeze can, in the space of 15 minutes, turn into a full offshore storm-force blast. Thus, we hugged the shore of every deep bay and cranny in the desert coastline, not daring to risk any crossings in the face of such unpredictable winds.

The deeper into the Gulf we paddled, the farther into the script of a National Geographic wildlife special we seemed to get. Giant storm petrels and black-browed albatross cruised above our boats without so much as a shiver of their great two-metre wingspans, and out in the Gulf, giant spouts of white revealed the breaching of the southern right whales that come here every spring to have their young.

On the breeze, which we both cursed for the extra work it entailed and thanked for its cooling effect on this 30-plus-degree day, we scented unmistakable barnyard odor that surrounds any large congregation of marine wildlife. This is something that is rarely mentioned in wildlife films—the olfactory unpleasantness that goes along with having hundreds of large mammals in a concentrated area. As we neared a boulder-covered beach ahead of us, the boulders began to move, and we heard the unmistakable cacophony of a southern sea lion colony. We later returned on foot and counted over 600 animals on less than 500 metres of beach. What happened when we paddled by this colony was unforgettable.

Sea lions are divided into small groups—harems of sleek brown females defended by an immense black bull. The daily routine seems to be filled with males bellowing—at their females, at other males, and apparently just for the fun of it. As we paddled near, many of the animals that had been sleeping woke with a start, even though we were a hundred metres off shore. Suddenly the air was filled with the sounds of hundreds of sea lions bellowing and charging down the beach toward us. Gravel sprayed in all directions as belligerent males attempted to maintain order, followed by a roar like a raging river as hundreds of curious animals plowed headlong into the sea, racing to check out the strange shapes just offshore.

Concern for our immediate safety mixed with a sinking feeling that our presence had disturbed these animals to the point of panic—an absolute no-no in the world of ecotourism. These misgivings quickly evaporated, however, as it became apparent that these animals weren’t disturbed—they wanted to play! Soon we had hundreds of sea lions nibbling our rudders, playing with our paddles and spy-hopping all around us to get a better view. A fun game developed as Kelly and her partner began to sprint with all their might. Although a sprint in a double Klepper is not much to be awed by, the following gang of hundreds of dog-like heads put a weeklong grin on us all. We regretfully pulled away and continued along the coast toward our next camp. Slowly, the following crowd thinned, but even three nautical miles along the coast we had an audience of nearly 100 sea lions laughing to themselves as we hauled our heavy boats above the high tide line and made camp.

One of the world’s last time machines

On a rare windless paddling day later in the trip, we held our breaths as a curious 17-foot infant southern right whale broke our 50-metre rule to investigate our small fleet. Mom followed—a 17-metre, 60-tonne chaperone. The whales circled us, swam under us, and nudged our boats with a gentle dexterity that belied their size. Before their curiosity got the better of us, we reluctantly paddled away toward our next camp, ending a once-in-a-lifetime encounter.

The name of these whales and their history highlights the importance of preserving areas such as this. The name “right” stems from the fact that they are huge, slow, and float when they are killed, making them the “right” whale to kill for whalers. American whalers alone took an estimated 200,000 southern right whales in the 18th century, and it was not until 1946 that the International Whaling Commission began to limit the catch of the rapidly vanishing cetaceans. Now, reserves like Peninsula Valdes provide a safe haven for these beautiful creatures to breed and raise their young. Calves are born between May and August, and the cow-calf pairs remain in these protected waters, safe from predatory orcas, until late December. Over 1,500 of the world’s remaining estimated 5,000 southern right whales use the waters of Peninsula Valdes, making the Peninsula a critical piece of habitat if this still-endangered species is ever to recover from the commercial slaughter.

Paddling Patagonia

Getting there:

A return flight from Toronto to Buenos Aires costs $1,500 to $3,000, depending on airline and travel dates. Plan several days to experience this cosmopolitan Euro-Latin city. From Buenos Aires, the Argentine airline Aerolineas offers reasonable flights to smaller centers. Prices fluctuate with the volatile Argentine economy, but at the time of writing a return flight from Buenos Aires to Trelew was around $120 US. From Trelew, a $10 bus ticket gets you to Puerto Madryn, where dozens of tour companies arrange 1–3 day excursions in the Peninsula Valdes region.

Season:

August to January. Most of the right whales have returned to their Antarctic feeding grounds by January, and the area gets scorching hot and packed with Argentine beach-goers in the summer months of January to March.

Related reading:

Dusk on the Campo, A Journey in Patagonia by Sara Mansfield Taber—an intimate portrait of the people still living a timeless lifestyle on Peninsula Valdes.

Attending Marvels—A Patagonian Journal by George Gaylord Simpson—an entertaining account of a young paleontologist’s fossil-collecting expeditions in the 1930s.

A Guide to the Birds and Mammals of Coastal Patagonia by Graham Harris—the definitive natural history handbook for the region.

In Patagonia by Bruce Chatwin—the Patagonian travel classic.

One clear night, Kelly and I opted to sleep on the soft gravel beach, under the Southern Cross and the rest of the unfamiliar constellations shining in the cloudless sky. For protection from the ubiquitous winds, we wisely pulled one of our boats broadside and slept head-to-head in its lee. At first light I awoke to a low, blubbery snore. Having heard all sorts of ominous tales of what a newly married fellow could expect from his wife the second the marriage papers were signed, I assumed the worst. But raising my head from my warm sleeping bag and peering over the kayak deck, I discovered that the cacophony came not from my lovely wife, but from the relaxed proboscis of an immense bull elephant seal sleeping not three feet away. It is difficult to imagine a four-metre-long, 3500-kilogram mound of snoring, gassy flab “sneaking up” on anything, especially on a gravel beach, but there he was. His Blubberness had somehow covered the 50 feet between the sea and our kayaks without waking a soul.

I woke to a low, blubbery snore. Having heard all sorts of tales of what a fellow could expect the second the marriage papers were signed, I assumed the worst.

Thankful for the kayak between us, I quietly roused Kelly, and we lay wide-eyed in our sleeping bags, zippers open, ready to beat a hasty retreat at a moment’s notice. Finally, my bladder called an end to this incredible encounter, and I slowly eased out of my sleeping bag. The bull reared up bellowing a warning, his elephantine nose drooping over a gaping pink mouth. Fortunately, he decided that the beach was all of a sudden too crowded for his liking, and he half rolled, half oozed his huge bulk back down to the water and swam away.

“I’m really glad he didn’t mistake us for female elephant seals,” breathed Kelly when we finally had calmed down enough to speak.

Peninsula Valdes is one of the world’s last time machines—an area whose original splendour seems to persist despite all the changes the last few centuries have etched on the face of the Earth. In crossing the threshold of the Isthmus of Ameghino and entering the Peninsula, one does more than step away from mainland South America— one steps back in time. Here, in the waters and on the arid campo of Peninsula Valdes, wildlife views us as bipedal curiosities—to them we are something really worth investigating. In a world of forests that have yielded to tree farms, grasslands swallowed by modern agriculture, and landscapes from desert to arctic peppered with the scars of resource extraction, Patagonia seems to endure in more or less its natural state. In this harsh yet rich and diverse land, we felt an awestruck humility, and were rewarded with a glimpse of the true Patagonia.

Dave Quinn is an expedition guide, wildlife biologist and outdoor educator. He lives in Kimberley, B.C., with his lovely wife, Kelly, and their loyal hound, Lucy.

Feature photo: Dave Quinn

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.