The Dumoine is not the most remote river. Its rapids not known for being perilous, its scenery not unmatched, its history not pivotal. I felt a little foolish being so excited as our shuttle bumped down the old logging road to the put-in at kilometer 64. My thoughts flitting to friends who were boarding bushplanes bound for rivers of the North and the far reaches of Quebec. Those were adventures.

Still, I knew the Dumoine was a river capturing the hearts of both master and novice, prime minister and artist, summer camper and wilderness guide. Did it, in fact, qualify as adventure—despite its preestablished campsites, well-mapped rapids and general accessibility? And if not, what makes it so special?

Aventure or bust: Why a Dumoine River trip is worth taking

If discomfort is an ingredient in adventure, this trip was proving itself when it had barely begun. Cultural discomfort. I was the only non-Francophone in the group, and though our guide Guillaume made an effort to give me instructions in English, he admitted he didn’t know the English translation of certain whitewater strokes or terms I would later learn to mean cross-draw and hanging cross-draw. For now I would have to learn those in French. Since I was learning how to whitewater paddle basically from scratch, you’d think this wouldn’t matter much—but you try remembering the difference between appel débordé and appel débordé de stance when you’re in the middle of a set of rapids and approaching the dreaded pleurer.

The group at least made sure I got the joke about the word pleurer, which refers to a rock that has water cresting over it, making it very difficult to see and dangerous to hit—and also means “to cry.”

If excitement is another prerequisite for adventure, this too was present in abundance. Though we portaged around the infamous Canoe Eater—or, as my French trip mates called it in English, Canoe Swallower—Dom and Simon still managed to take a swim while we practiced grabbing the contre-courant at the bottom. And when descending Rapide Sleeper, all five of our canoes filled to the gunwales with water, forcing us to submarine to shore to dump them out.

Running “Rapides Big Steel”

If success is necessary, if only to distinguish adventure from misadventure, we cleared that standard on day four on Rapides Big Steel, the biggest and most technical rapid we’d attempted yet. With Guillaume in the stern, I hadn’t felt very nervous for any of the rapids so far, but I had to remind myself to take deep breaths as we led the charge. I hoped Guillaume could tell where we needed to enter the rapid because the place that had seemed easily discernible from downstream as we scouted was unidentifiable to me now.

Once we were in, the water immediately pushed us toward a pleurer, as Guillaume had told us it would. I heard him yell, “Fort! Fort!” and I knew it must be serious as up until this point he’d always yelled, “Hard! Hard!” when he needed me to paddle hard. We both dug in, shot past the pleurer, were rocked over a few more waves that sent water crashing over the bow and then swung around to make sure everyone else made it through. We’d avoided misadventure, some of us with more water in our boats than others—from the river or les pleurs I’m not sure.

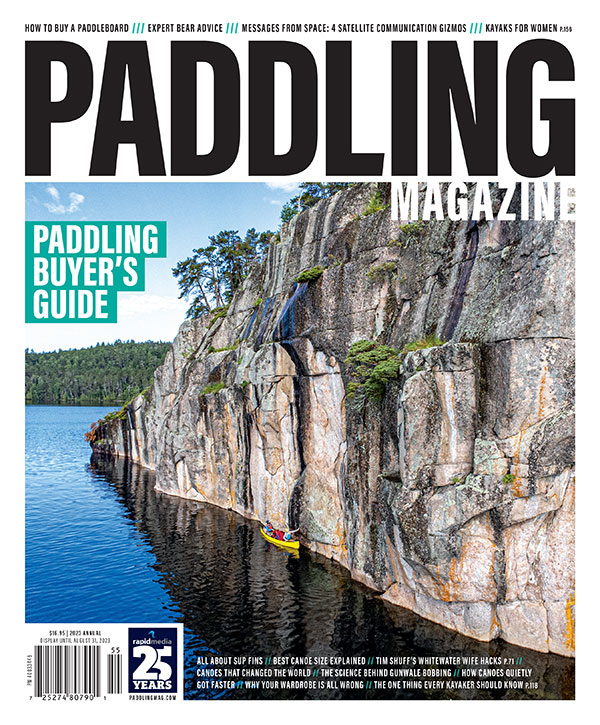

If adventure is a feeling, we felt it most as we rounded the corner to Bald Eagle Cliff on the second-last day of our trip, the river narrowing and the trees seeming to get taller and the hills larger. We were less than 15 kilometers from civilization now, but we seemed all the more remote in both distance and time. The slap of a beaver’s tail only confirmed this suspicion, echoing back to both the fur traders who used to travel the Dumoine and the Algonquin bands who used to live here and believed the river was carved out by a great beaver being chased by the Trickster.

Adventure comes in many sizes

If adventure must be extreme, though, so as to only be undertaken by the most experienced in the sport, I couldn’t see how our trip down the Dumoine qualified. As we headed down the last stretch of river toward the Ottawa, I wondered aloud to Guillaume whether modern adventure authors we had both read were right, that true adventure is only big, harrowing and risky. Guillaume paused and then wondered back: how many people had this sentiment kept from getting out there, because they thought it wasn’t worth doing if it couldn’t be big?

“If sleeping in the woods one night is an adventure to someone, I hope they go out and do it and not feel it is too small to be considered an adventure,” he said. This from a man who cross-country skied 600 kilometers from Rouyn to Montreal in minus 35-degree-Celsius weather and spent 55 days on board a sailboat living in colonial conditions as it crossed the Atlantic.

This was the sheen of the Dumoine, I realized. Meeting paddlers where they are at and offering trips that are still remote, still challenging, still steeped in history. Still adventure.

Digital editor Marissa Evans is filling in for Kaydi Pyette as editor of Paddling Magazine. This is her first issue.

Mario being expertly guided by Danny down Rapides Examination on day five of the trip. | Feature photo: Marissa Evans

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.