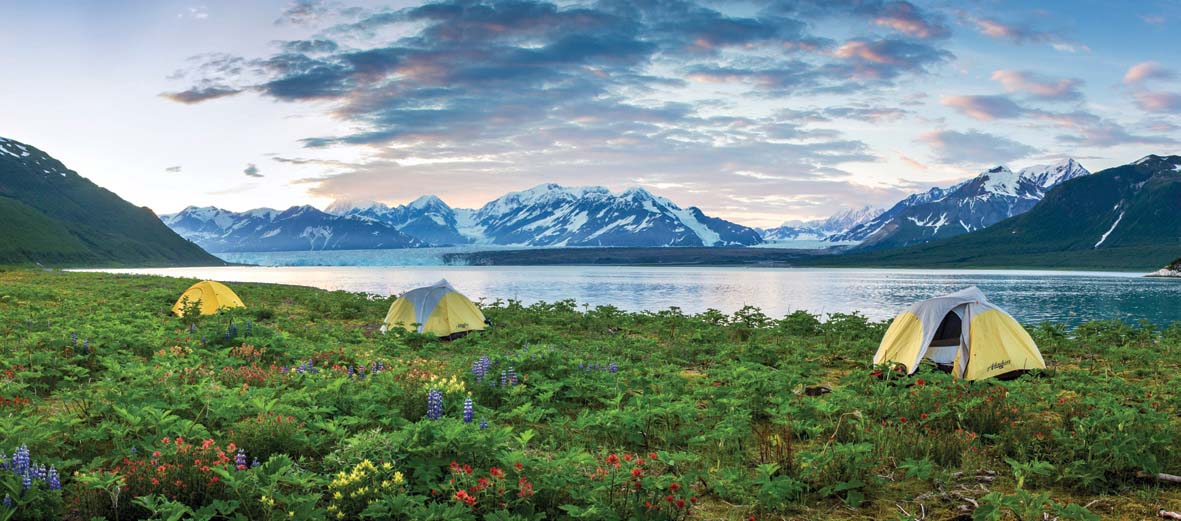

Above the northernmost reach of the Alaskan Panhandle, sardined between piles of camping gear, food-stuffed dry bags and folding kayaks, I pressed my face to the cool window and gazed beyond the plane’s wing cleaving the cloudy firmament. My first glimpse of Russell Fiord.

After flying over the forelands, a flat buffer of marsh that lies between the small coastal town of Yakutat, Alaska, and the fiord, the de Havilland Turbo Otter lifted over the ridgeline to expose the length of the 17-mile inlet. The face of Hubbard Glacier, the longest tidewater glacier on the continent, guards the inlet’s mouth, dumping ice into the surging current. The port wing dipped low as we rounded a final, sharp peak and quickly dropped altitude. The gravel rose to meet the plane’s tundra tires, the oversized balloon wheels bouncing down the wild beach to a hasty stop.

Out the window, the scene looked more like the primary colors of a child’s finger-painting than a natural landscape. Glacial silt suspended in its depths turned the water a luminous blue, and between the snowcapped mountains and the sea, an explosion of brilliant purple lupine, scarlet paintbrush, golden cinquefoil and creamy dwarf fireweed engulfed the shoreline.

The wildflowers that make Russell Fiord such a remarkable destination are the result of its unique quirks of glaciology and geology. The Hubbard is one of few glaciers in the world that has been steadily advancing since it was first mapped in 1895. Twice in recent history—in 1986 and 2002—the face of the glacier advanced enough to create an ice dam at the mouth of the fiord. With no outlet, the waters rose as much as 80 vertical feet, inundating the shoreline under a brackish lake. In both cases, the ice dams eventually failed, flushing the retained water back to the sea and exposing a bathtub ring of newly open habitat on which wildflowers were quick to colonize.

As I paddled along the shoreline circumscribed by blooms and falling ice from Hubbard’s face, I wondered how to reconcile this advancing glacier with the growing concern surrounding climate change. The Hubbard seems a graphic contradiction to the narrative that global climate change means a less icy planet.

OUT OF BALANCE

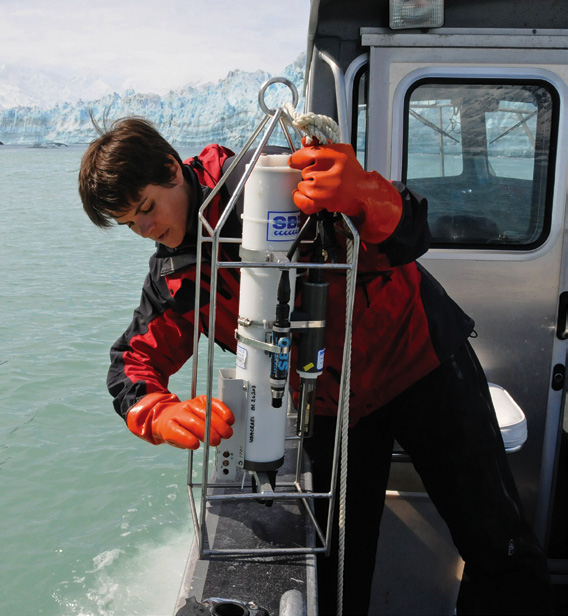

Dr Leigh Sterns is a researcher from the Glaciology and Remote Sensing Group at the University of Kansas who has extensively studied the fickle nature of the Hubbard. Her latest research, just recently published, explains why a glacier like Hubbard can rapidly advance in spite of a warming climate.

“The long-term trend is that the Hubbard is advancing because it needs to reach a stable balance between accumulation [the amount of snow and ice that falls on the glacier] and ablation [the amount of ice it discharges],” she says.

For a glacier to be in mass balance, neither accumulation nor melt can dominate. Long before it was mapped, the Hubbard fanned out well beyond its current limits. Then, at some point, it began retreating to its current pinch point. This small, geologically-restricted melting zone, combined with the sheer enormity of the glacier, now tips the scale in favor of advance.

“The really amazing fact is that it takes a glacier as out of balance as the Hubbard to be advancing in today’s climate,” Stearns adds.

A common refrain from climate change skeptics is that these changes are part of natural oscillations, not the result of human activities. After all, the history of Southeast Alaska is rife with these fluctuations. Over the past 10,000 years this land has been uncovered and recovered with ice five separate times. It’s tempting to think that our current warming spell is part of this natural process.

But Stearns points to the alarming rapidity and uniformity of glacial retreat across the globe. She also notes that if you just look at our natural climate cycle, we should be in a cooling period now, which recent climate data—and recent memory—shows clearly we are not.

THE POSTER CHILD FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

In many ways, Alaska is the poster child for the effects of climate change. The flora, fauna and human communities have evolved for annual, deeply cold winter seasons and short, cool summers. Today, however, the mean annual temperature in Alaska is 3°F warmer than 50 years ago, double the average national increase, and well above the accepted 2°F global warming limit underlined at December’s UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. Villages are eroding as permafrost melts and sea levels rise, and native species are disappearing, taxed to their ecological limit.

Polar areas are our anchors to windward, and our canaries in the climate coal mine. According to Harvard climate scientist James Anderson, the swiftly melting Arctic ice cap and Antarctic ice sheets are barometers of an approaching climactic storm. He points to the 80 percent loss of Arctic sea ice, measured by volume, in the last 30 years. “Nobody predicted it. Nobody forecast it. Nobody quantitatively understands it today, except we know it’s happening at a breathtaking rate,” he says.

And that rate is increasing. As the ice cover in northern Alaska, the Arctic Archipelago and Siberia melts, it will expose soil, releasing additional carbon into the atmosphere, hastening the process even further. Anderson forecasts the end to all permanent sea ice in the Arctic by 2025.

“When we lose that floating ice,” he says, “the temperature differential starts to drop between the polar regions and the tropics, and as soon as that starts to occur, the entire climate structure starts to shift.” Most of us are familiar with the dire predictions of such a shift: flooded seaboards, increasingly unpredictable and violent weather, food shortages, mass extinctions.

For every tale of a warming climate, though, there is an example that bucks the trend: an exceptionally cold winter, heavy snowfall, or a glacier that’s growing rather than melting. These anecdotes are the fuel that feed the controversy and confusion surrounding human-induced climate change and often stall meaningful action to slow our current trajectory.

“Climate change seems remote, it’s indirect, the timescale is long, and it’s driven by a collective process rather than an individual action,” notes Dr. Lauren Oakes, an ecologist and recent Stanford graduate who studies the impacts of our changing environment on temperate rainforests and communities in Alaska.

Oakes is no stranger to the counterintuitive impacts of climate change. She and her research crew spent three seasons traveling by kayak and camping at remote field sites in Southeast. Specifically, she studied yellow-cedar, a species of slow-growing, long-living trees that range from northern California up through Southeast Alaska’s coastal old-growth forests. The species is in decline, with massive die-offs observed since the end of the 20th century. Ironically, our warming climate is causing the trees to freeze to death.

Yellow-cedar relies on consistent snowpack to insulate its shallow root system. Ordinarily, the trees prepare for winter by shunting resources from their branches and roots, but uncharacteristically warm early spring weather is reducing the insulating snowpack and reinvigorating the trees too early. Subsequent cold snaps freeze the exposed and unprepared trees, leading to a gradual death.

I recently paddled with Dr. Oakes at her old stomping grounds in Glacier Bay, a landscape etched by the climatic shifts that drive the advance and retreat of glaciers. As Oakes and I paddled toward John Hopkins Glacier, we talked about the disconnect between scientific reality and public perception.

“We have a good understanding of climate change and it is always getting better, but part of science is uncertainty,” Oakes acknowledges. “The problem is how that uncertainty is portrayed and viewed by the public.”

Sipping glacial ice margaritas at camp one night, I circled back to this idea of uncertainty. “The thing I find so appealing and exciting about science is that there is always something to discover,” Oakes confides, “but the flip side of that means that there will also always be some things that we don’t yet know, that are waiting to be understood.”

WHOLESALE DENIAL

Alaska’s position on the frontlines gives the state an opportunity to lead the way in climate change recognition and research, but it won’t be easy. “For the last five or 10 years, there has been a growing, but reluctant, acceptance among Alaskans,” about the significance of the issue, says Alli Harvey, a Wild America Campaign Representative for the Sierra Club in Anchorage.

Unfortunately, she hasn’t seen that message incorporated into the state’s policies. In fact, there seems to be wholesale denial among many representatives. Both of Alaska’s Senators voted against a bill admitting human activity has significant impact on the climate, and the state’s single federal Representative, Don Young, charges that any surety of our role in climate change is “a tremendous disservice to science and society.”

Consider this analogy: imagine a kayaker crossing a wide river above a rapid. A perceptive paddler will gauge the current, set a ferry angle to counteract its effect, and reach the far shore above the rapid. By turning a blind eye to humans’ role in climate change, we revoke our agency and absolve our responsibility to take corrective action—essentially, it is like getting into the middle of the channel, then denying that you have a paddle at all.

Alaskan politicians not only wish to ignore the current of climate change, but some like Governor Bill Walker are advocating that the solution is to paddle directly into the maelstrom. In response to the threat of rising sea levels, Governor Walker recently proposed that immediate drilling in the protected Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is needed to fund mitigation and relocation projects for affected villages. This despite research released just months earlier urging all remaining Arctic oil and gas be left in the ground to help keep global temperature rise below catastrophic levels.

But there is change on the horizon. In 2013, Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins was elected to the Alaska State House of Representatives in an upset race against an incumbent, Big Oil proponent. Since then, he’s risen from third youngest official ever elected in the state to a respected politician and staunch advocate of responsible energy development.

There is another story that few know about Kreiss-Tomkins: just a year before he began his campaign, he spent the summer leading a pioneering study to address the effects of climate change on Alaska’s alpine glaciers. To access the remote bays on approach to his climbs he, like Dr. Oakes, relied on kayaks as his primary transportation.

THE SYMBOL OF THE KAYAK

In an era when people spend less time interacting with their natural environment, paddlers may understand climate change better than most, simply because we spend more time outside. Paddlers ply the transition zones between water and land where climate change is wielding some of its greatest impacts. We pay attention to river levels. We know when floods come early, late or not at all. We notice when our lake levels drop.

Nationwide, we’re raising our voices to call for more responsible energy development. Thousands of boaters in Seattle and Portland, as well as smaller gatherings throughout the country, came together in 2015 to protest Arctic drilling, making this a groundswell year for paddlers engaging in the climate movement. It even added a new term to the nation’s lexicon: kayaktivism.

“The kayak is now a symbol for demanding a sea change in our approach to energy use and development,” says the Sierra Club’s Alli Harvey. She believes significant credit for Shell’s decision late last summer to cease oil exploration in the Arctic—closing the door on an eight billion-dollar investment—is due to the paddlers who spoke out.

Not everyone appreciates kayaktivism, though. Social media trolls were quick to bemoan the hypocrisy of using petroleum-based craft to protest fossil fuel. Harvard science historian and Merchants of Doubt co-author Naomi Oreskes, in an interview with The Nation, offered perhaps the most compelling rebuttal of the alleged irony of a flotilla of plastic kayaks in Seattle Harbor protesting beneath the hulking carapace of Shell’s Polar Pioneer oil rig.

“People in the North wore clothes made of cotton picked by slaves. But that did not make them hypocrites when they joined the abolition movement,” Oreskes points out. “It just meant that they were also part of the slave economy, and they knew it. That is why they acted to change the system, not just their clothes.”

THE CONTROVERSY AND CONFUSION SURROUNDING CLIMATE CHANGE OFTEN STALL MEANINGFUL ACTION.

If kayaks are the new symbol for the climate movement, our job as paddlers is to continue this momentum at whatever scale we can. Some, like Australian kayaker and Kayak4Earth blogger Steve Posselt, have used transcontinental expeditions to highlight the issues, but local actions are just as meaningful. Organizing a small floating protest, giving a presentation at a local paddle shop, or simply taking others outside to build their connection with natural systems add extra strokes to counter the current.

Across the nation, individuals and institutions—from colleges and universities to media companies and charitable funds—are divesting from fossil fuels. “Look to see if your retirement fund is invested in fossil fuels,” suggests Harvey, “or more broadly, look to see where your municipality or college is investing, and then reinvest in more sustainable, local, proactive, renewable energy programs.”

We are standing on the shore of a swelling river. The current is accelerating, and downstream, the roar of the rapids is growing louder. The solution lies in navigating those uncertain waters; getting across will require thoughtful planning and the dedication of visionaries like Stearns, Oakes and Kreiss-Tomkins. And it will require many, many collective paddle strokes from those of us with an understanding of tricky crossings.

A. Andis is the former Wilderness Director for the Sitka Conservation Society and an Alaskan kayak instructor and photographer. He is currently completing a graduate degree in Environmental Studies in Missoula, Montana.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.