In a 17th-century fortress high in the Pyrenees Mountains near the Spanish border is a sea kayak. It’s a beat-up folding model from the 1930s, and rests on a stand in the Room of Honour at France’s National Commando Training Centre, where the country’s special forces learn the ropes. The battered wood-and-canvas boat offers a window into the little-known military use of kayaks.

How the humble kayak helped win wars and write history

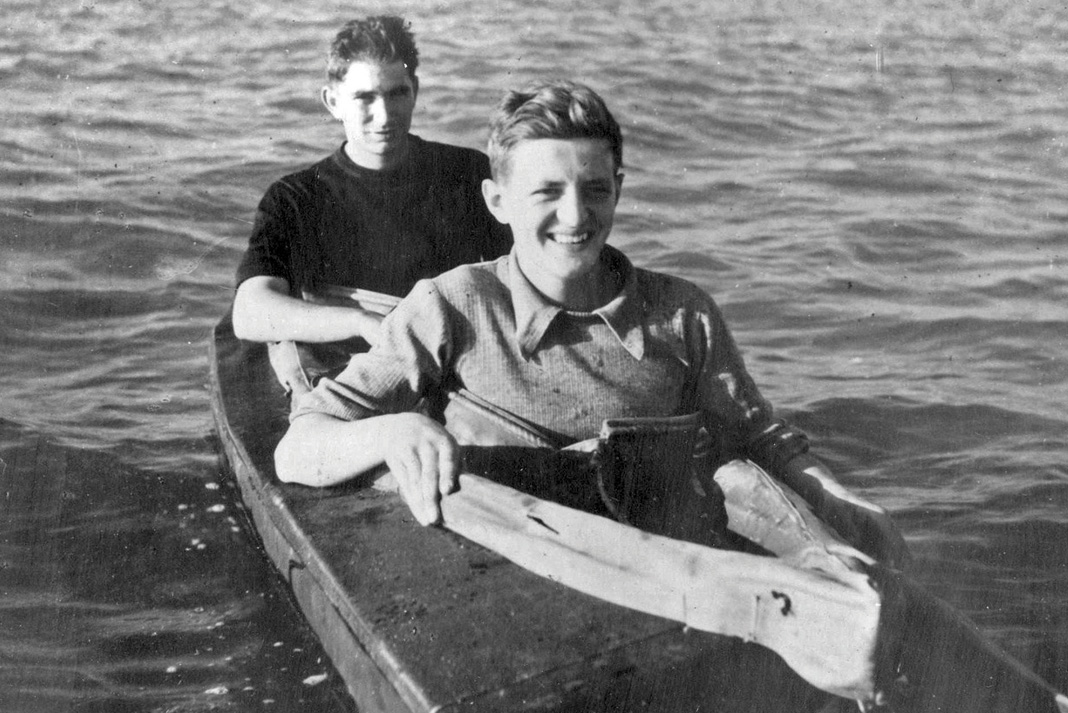

In 1943, two young Frenchmen named Michel Brousse and Georges Schlumberger headed south from Paris. In the midst of the Nazi occupation, they left their reasonably secure existence as university students to make their way to Algeria and join the French Resistance. Schlumberger had trained on the Creuse River four years earlier with French adventurers Genevieve and Bernard de Colmont and Antoine de Seynes. He knew of the trio’s 1938 descent of the Colorado and Green rivers—a pioneering journey documented by Ian McCluskey in the 2015 film, Voyagers Without Trace—and asked de Seynes to borrow the 17-foot kayak he’d paddled through the whitewater canyons.

Brousse and Schlumberger managed to sneak the kayak to France’s southern coast. From there they paddled at night and ate raw fish to avoid campfires and evade detection until they reached Spain. After a run-in with Spanish authorities that ended in their arrest and the kayak’s confiscation, the pair eventually made their way to North Africa to join the Resistance. Schlumberger died fighting in the Battle of Vosges in 1944; Brousse survived the war and returned to Spain in 1948 to reclaim the kayak that had helped them join the fight.

To this day, trainees in the French Commandos eat a dinner of raw sardines and then reenact Brousse and Schlumberger’s 115-mile night paddle from Canet-en-Roussillon to Mataró, Spain.

Kayaks commandos in Operation Frankton

The Frenchmen weren’t the only ones to recognize the wartime potential of kayaks’ stealth and silence. On the night of December 7, 1942, the British submarine H.M.S. Tuna surfaced 10 nautical miles off the French Atlantic coast. Five tandem kayaks slipped into the water. Their mission: blow up German supply ships in Bordeaux harbor, several days’ paddle into occupied France.

Strong crosswinds, tidal currents and five-foot seas made for a treacherous crossing, capsizing one of the kayaks and blowing another off-course. A third kayak became separated from the others later in the night. The remaining marines worked their way 60 miles up the Garonne River, paddling at night and hiding during the day. On the fifth night, they reached Bordeaux and attached limpet mines to six German ships, then set out on foot to escape to Spain. Only two men survived. Six were captured and executed by the Germans, and the capsized duo succumbed to hypothermia.

Churchill believed Operation Frankton shortened the war by six months. The Combined Operations commander hailed the raid as the most “courageous and imaginative” operation carried out by the Royal Marines. Folding kayaks are still used today by British and French Special Forces.

The stories of Brousse and Schlumberger and Operation Frankton remind us that we’re fortunate to paddle for pleasure. We have the luxury of slipping stealthily across the water because we enjoy spotting wildlife, not because we have to sneak past patrol ships in the dead of night.

As Captain Quevarrec of the French Commandos says of the war-torn kayak in the Room of Honour, “The pen allows the philosopher to deliver his thoughts, the sword allows the samurai to protect the emperor, the kayak allows adventurers to go somewhere.” Where we go, and why, will vary.

Neil Schulman celebrates kayaking’s diverse heritage in Reflections.

Brousse and Schlumberger in 1943. The pair used a kayak to sneak out of occupied France and join the Resistance in North Africa. | Feature photo: Courtesy Voyagers Without Trace

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.