We all saw this coming. During the 2024 U.S. presidential campaign, Donald Trump frequently expounded on his love for tariffs, a variety of tax on international trade he calls “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” The president made liberal use of tariffs in his first administration, starting in 2018 with a series of levies that roiled the paddlesports industry. And when Trump left office in 2021, his successor Joe Biden kept many of those tariffs in place.

Since regaining office in January 2025, Trump has used tariffs and the threat of tariffs as a cudgel against friend and foe alike. By April, he had tariffed nearly every country on the face of the Earth, with special attention to America’s two biggest trading partners, Canada and Mexico, and its greatest economic rival, China. Dozens of countries announced counter-tariffs, both targeted and broad-based.

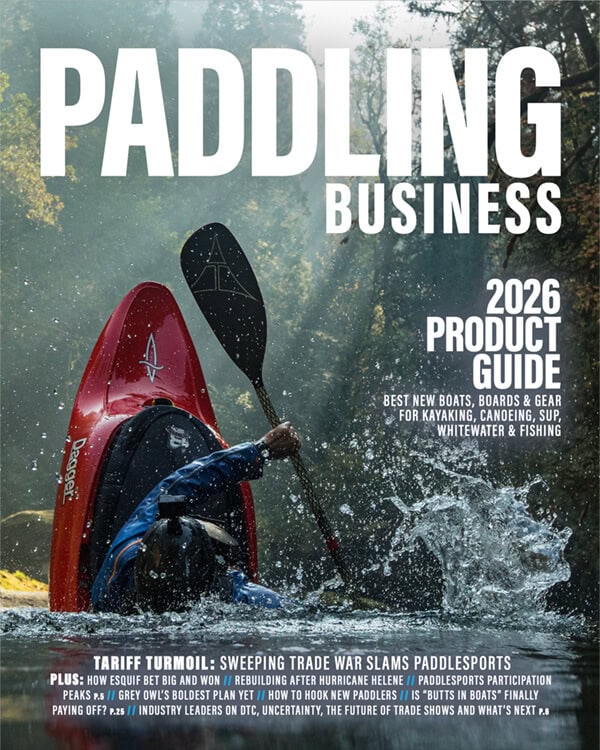

Sweeping trade war hits paddlesports from all sides with little relief in sight

Paddlesports is vulnerable

Paddlesports is a globally integrated industry, straddling the retail, service and manufacturing sectors. The United States, Canada and Europe all make boats and paddling gear, and all import boats and equipment from each other. As a globally integrated industry, tariffs hit the paddlesports business both coming and going.

The supply chain economist Jason Miller has tracked tariffs by North American Industry Classification System [NAICS] codes, and found that sporting goods is among the three most-affected market segments among hundreds of demarcated industries.

“Outdoor products and paddlesports particularly are just incredibly susceptible because you have inelastic price demand for durable goods,” says former Eddyline CEO Scott Holley, now with the Eccles School of Business at the University of Utah. “What you’re paying tariffs for is a larger portion of the finished product compared to something like electronics where you’re buying a lot of engineering talent and marketing. In paddlesports, the ratio of goods that are tariffed to services within the cost structure is much higher.”

Okay, class dismissed. How does that play out in the real world? If you ask almost anyone in the paddling business, they’ll say it sure would be nice to know. Because right now it’s still anyone’s guess.

“Business owners can handle pretty much anything except for unpredictability. We can predict a lot, but we can’t predict what the president is going to do today,” says Rutabaga Paddlesports owner Darren Bush. “We’re living in a roulette wheel.”

Sea Eagle partner John Hoge is no stranger to the tariff game. During the last round of Trump tariffs starting in 2018 he proved to be a savvy player, applying for and receiving exemptions for the drop-stitch kayaks and aluminum paddles he imports from Asia. Those exemptions expired after 18 months, and Biden kept many of the so-called Trump tariffs in place when he took office in 2021. In the interim, Sea Eagle had moved the bulk of its inflatable kayak production from China to Vietnam. In January this year, Hoge told Paddling Business the shift had given him a relative leg up on competitors who stayed in China.

Weeks later, Trump announced a new 46 percent tariff on Vietnam.

“When it comes to tariffs, I’m pretty much in a Jesus-take-the-wheel mindset.”

—Simon Coward, AQ Outdoors

The episode illustrates the unpredictable tariff environment paddlesports finds itself in. Hoge was not immediately impacted by the increased Vietnam tariffs because he had filled his warehouse with product between the U.S. election in November 2024 and President Trump’s inauguration on January 20th this year. That strategy has paid off—so far.

“A company’s reaction could be ingenious if it’s in anticipation, or ruinous if you zig when Trump zags,” he says. “With 145 percent Chinese tariffs, a whole bunch of crazy stuff starts to make sense. But if you put a couple million bucks in that direction and then [the Chinese tariff] goes back to 30 percent—like it did—that’s all wasted.”

In July, President Trump announced he’d reached a deal with Vietnam to stabilize tariffs at 20 percent. Hours later, Politico reported that the rate in a draft agreement painstakingly negotiated by both sides had in fact been 11 percent. As Paddling Business went to press no formal deal with Vietnam had been signed.

The roulette wheel spins on.

No winners, just losers

President Trump claims his tariffs will revitalize American manufacturing and make the United States “rich as hell.” If those policies boost any American industry, it should be paddlesports. Hardshell boats are produced all over the world—in China, Europe, Canada and in the United States, where leading brands compete effectively with foreign rivals at every price point.

If any companies were to benefit from tariffs, it should be the likes of Jackson Kayak in Sparta, Tennessee, BIG Adventures in Fletcher, North Carolina, and Confluence in Greenville, South Carolina. Yet those companies report tariffs have actually hurt their business, both at home and especially abroad. All export to countries that have enacted retaliatory tariffs on American goods. Meanwhile, the Trump tariffs have increased materials costs, sometimes dramatically.

“Nobody’s gaining because even for American-made boats, the plastic came from China,” says OKC Kayak owner Dave Lindo. “The screws, the fittings, the seats—all of it came from abroad.”

Chinese plastic can be tariffed both coming and going because the polyethylene trade between the U.S. and China is a circular one. China consumes 38 percent of U.S. ethane-ethylene exports, much of which returns stateside as toys, drainpipes, sandwich bags, and the high-density polyethylene pellets many U.S. kayak manufacturers mold into boats. In March, Trump boosted the tariff on the import of Chinese plastic from 10 to 20 percent. While modest compared to the levy on many other Chinese products, this adds up to real money: China exported $18.2 billion worth of plastic to the United States in 2024. If the trade volume remains the same this year, American importers will pay an additional $3.6 billion in tariffs just to take delivery. Though paddlesports accounts for a tiny sliver of those U.S. plastics imports, plastic feedstock is the biggest single material expense for every kayak manufacturer.

In April, Trump imposed a 25 percent levy on all steel and aluminum imports to the United States, and then doubled the tax to 50 percent in June. The impact is impossible to avoid, even for manufacturers that source materials domestically.

“Our fastener suppliers make our stainless-steel bolts here, but guess where they buy their metal? It’s not the United States,” says Jackson Kayak Director of Sales Colin Kemp. “Even now, depending on the vendor, we’re already getting hit with 15 percent cost increases because of tariffs.”

Meanwhile, retaliatory tariffs from the EU and Canada are decimating export markets for U.S. paddlesports firms. Six years ago, a 25 percent EU tariff on U.S. kayaks and canoes made it nearly impossible for American companies to remain price-competitive, and the cost of U.S.-made paddlecraft remains high throughout Europe.

“Today a Waka Billy Goat is €1,399 ($1,622 USD) at my local shop. A Jackson Gnarvana is €2,499 ($2,898 USD),” an Irish paddler reported on Reddit in June. “Sales of U.S.-made stuff is going to shrink massively.” Jackson kayaks are made in Tennessee; Waka kayaks in Italy.

Jackson and other U.S.-made kayaks are also more expensive in Canada. Western Canoe Kayak in British Columbia stocks the Gnarvana for $2,475 CAD ($1,803 USD)—about $200 more than the typical stateside price. Those prices could well increase later this season or next year, after retailers sell through inventory they imported before Canada’s retaliatory tariffs took effect.

“Business owners can handle pretty much anything except for unpredictability…We’re living in a roulette wheel.”

—Darren Bush, Rutabaga

The Trump tariffs, and the president’s aggressive language about making Canada “the 51st state,” have provoked a powerful backlash, with 78 percent of Canadians telling the Angus Reid Institute they are buying fewer American products in response. “All the major supermarkets here are highlighting what’s Canadian and what’s not,” says Simon Coward, owner of AQ Outdoors in Calgary. The saving grace for American paddlesports companies selling into Canada is the relative dearth of made-in-Canada alternatives.

“We wouldn’t have any product if we didn’t have U.S. product. We’d be selling Level Six and Salus and I don’t know what else,” Coward says.

AQ Outdoors’ drysuit rack is a microcosm of the tariff effect on paddlesports. The Calgary specialty retailer sells Level Six from Canada, Asian-made suits from NRS, and Kokatat from the United States. Level Six ships tariff-free within Canada, and NRS avoids duties on products it ships directly to Canada from Asian factories. Kokatat must pay Canada’s 25 percent retaliatory tariff on U.S. goods. As a result, Coward says, the Kokatat price has shot up relative to the Canadian and Asian competition. “Level Six and NRS drysuits range from $1,300 to $1,800 CAD ($950 to $1,300 USD), and now Kokatat drysuits are $2,500 CAD ($1,800 USD),” Coward says.

“These tariffs have really impacted our exports,” says Steve Jordan, who handles international and domestic sales at BIG Adventures. The North Carolina-based manufacturer of Liquidlogic, Native Watercraft and Bonafide kayaks worked hard to keep its foothold in Europe during the first Trump administration, when the European Union answered U.S. tariffs with a 25 percent import tax on canoes and kayaks. “A lot of brands pulled out of the European market because of those tariffs, but we stayed committed. We got very creative with our distributor in Germany to find ways to minimize the impact, and we were able to survive it.”

To Jordan, the second Trump administration feels like déjà vu with a twist. “Now we’re faced with another tariff and a big part of it is just the uncertainty. One minute it’s 25 percent, one minute it’s going to be 50 percent,” he says. “It’s hard to manage your strategy when the tariffs are just all over the map.”

No sudden moves

The tariffs have left everyone in the paddlesports industry mulling the sticky question of how much of the tariff costs they should—or can afford not to—pass along. For many, the question is a matter of forecasting. They still have warehouses full of imported goods, and the tariff environment remains, to put it very simply, fluid.

“If there’s anything we’ve learned throughout this tariff situation is that it can change on a dime,” says NRS Chief Marketing Officer Mark Deming. “Our philosophy is to stay the course for now and monitor it really closely. When we need to make a move, we’ll make a move, but we’re not going to make knee-jerk decisions we might have to reverse.”

“In these times, the old saying that hope is not a strategy doesn’t apply. Hope is the only strategy.”

—John Hoge, Sea Eagle

Coward initially spent a lot of time trying to plan for tariffs, before deciding just to watch his brokerage invoices and adjust prices as needed. “It’s a bit reactive, which we don’t love being, but being too proactive in such tumultuous times can be a bit of a time suck,” he says. “When it comes to tariffs, I’m pretty much in a Jesus-take-the-wheel mindset.”

While the full impact on pricing won’t become clear until brands release their 2026 price lists, some companies already have announced midseason increases, citing the cost of tariffs. “We’ve gotten letters saying tariff prices are in force as of today, from accessory brands as well as boat manufacturers, so the tariff effect from Donald Trump is already here,” OKC Kayak’s Lindo told Paddling Business in June. The Yale Budget Lab estimates Trump’s tariffs could cost the average American family an extra $2,400 this year. That leaves precious little for discretionary purchases like boats and paddling gear.

“The problem is people are resisting buying at the old prices,” Lindo says. “They’re not going to buy it at this new price at all.”

Consumer confidence in the United States has declined sharply since January, and the mood looking forward is glum. The Conference Board’s Expectations Index—a monthly assessment of consumers’ short-term outlook for income, business and labor market conditions—dipped to 69 in June before rebounding to 74.4 in July—still well below the threshold of 80 that typically signals a recession ahead. The retreat in confidence was shared by all age groups and political affiliations, and almost all income groups. Notably, tariffs remained on top of consumers’ minds and were frequently associated with concerns about inflation, high prices and the negative impact of tariffs on the economy.

The Conference Board and similar surveys are focused on the entire U.S. economy or industry segments far larger than paddlesports. To assess the impact on paddling specialty retail, livery operations and manufacturing we must rely on anecdotal reports. Those are not good.

In a business environment characterized by slow sales and uncertain demand, the last thing paddlesports needs is increased taxes—let’s not forget that tariffs are a type of tax—and more uncertainty. That’s what the industry is facing now, Hoge says. “We have to place orders from Vietnam and in theory that could snap back to 46 percent. That would be ruinous,” he says.

And if it does?

“We’re just hoping it doesn’t,” he says. “In these times, the old saying that hope is not a strategy doesn’t apply. Hope is the only strategy.”

The Explainer, Tariff Edition

Some (but not all) of President Trump’s tariff actions in one sentence

Ready? Deep breath … Go!

Since taking office on January 20, 2025, President Donald Trump has launched sweeping trade policies centered around import taxes, aka tariffs, on goods from nearly every country on the planet, starting with his announcement hours after being sworn in that America’s two closest neighbors and biggest trading partners, Canada and Mexico, would pay for their inability to stop the flow of fentanyl from Mexico (and imaginary fentanyl from Canada) with 25 percent tariffs; then on January 25, 2025 Trump announced a 60 percent tariff on all Chinese imports including electronics, electric vehicles, non-electric vehicles, steel, textiles, and more, as part of an “economic decoupling strategy” from the world’s second-biggest economy; then on February 11, Trump resurrected a 25 percent tariff on all foreign steel and aluminum; and then on March 11, Trump aimed his ire at the fentanyl lords of the Great White North, threatening to double tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum and maybe annex the whole country, which got Mark Carney elected prime minister; followed on March 13 by a 60 percent tariff on Vietnamese electronics and textiles because, according to Trump (and pretty much everyone else) Vietnam was and still is acting as a proxy for Chinese companies; then on March 26 Trump announced a 25 percent tariff on Mexican and Canadian automobiles and auto parts (in apparent breach of the United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, which Trump himself negotiated in his first term and hailed as “the best agreement we’ve ever made!” so he later backed off of those tariffs); all of which was prelude to April 2 (“Liberation Day”) when Trump announced a 10 percent baseline tariff on imports from almost every country in the world, including uninhabited islands but not Russia, plus higher “reciprocal” tariffs on dozens of countries that, briefly, pushed tariffs on Vietnamese imports to 45 percent and China tariffs to 145 percent, causing the global stock markets to plunge and Trump to suspend the reciprocal tariffs for 90 days to give countries time to make deals with the White House, which none did, so then Trump extended the deadline to August 1; but in the meantime, he doubled steel and aluminum tariffs to 50 percent and the administration later announced that the United States had collected $27.2 billion in tariff revenues in the month of June, which is a lot of money but probably not enough for Congress to replace portions of federal income tax with tariff revenue as the president has suggested and experts warn would drive inflation, provoke retaliatory tariffs, upend supply chains and destabilize global markets; and then, on July 27, the president announced “the biggest of all the deals,” setting a 15 percent tariff on most U.S. trade with the European Union, and no tariff on U.S. goods going the other way, which brings us to August 21, when Paddling Business went to press, and if you don’t like the tariffs now just wait, because U.S. tariff policy is like the weather in Maine, it changes every five minutes.

Sporting goods is among the three most-affected market segments among hundreds of industries affected by tariffs. | Feature photo: Alamy

This article was first published in the 2025 issue of Paddling Business.

This article was first published in the 2025 issue of Paddling Business.

Thank you for addressing this issue. The economic impacts of the Trump tariffs on outdoor recreation will be devastating in both the short and long-term if they continue. To say nothing of the negative impacts of the Trump administration on conservation, environmental and health regulations.