In 2022, Cyril Derreumaux kayaked solo and unsupported from California to Hawaii, relying entirely on human power—a feat that came mere years after he’d sworn off long-distance ocean paddling.

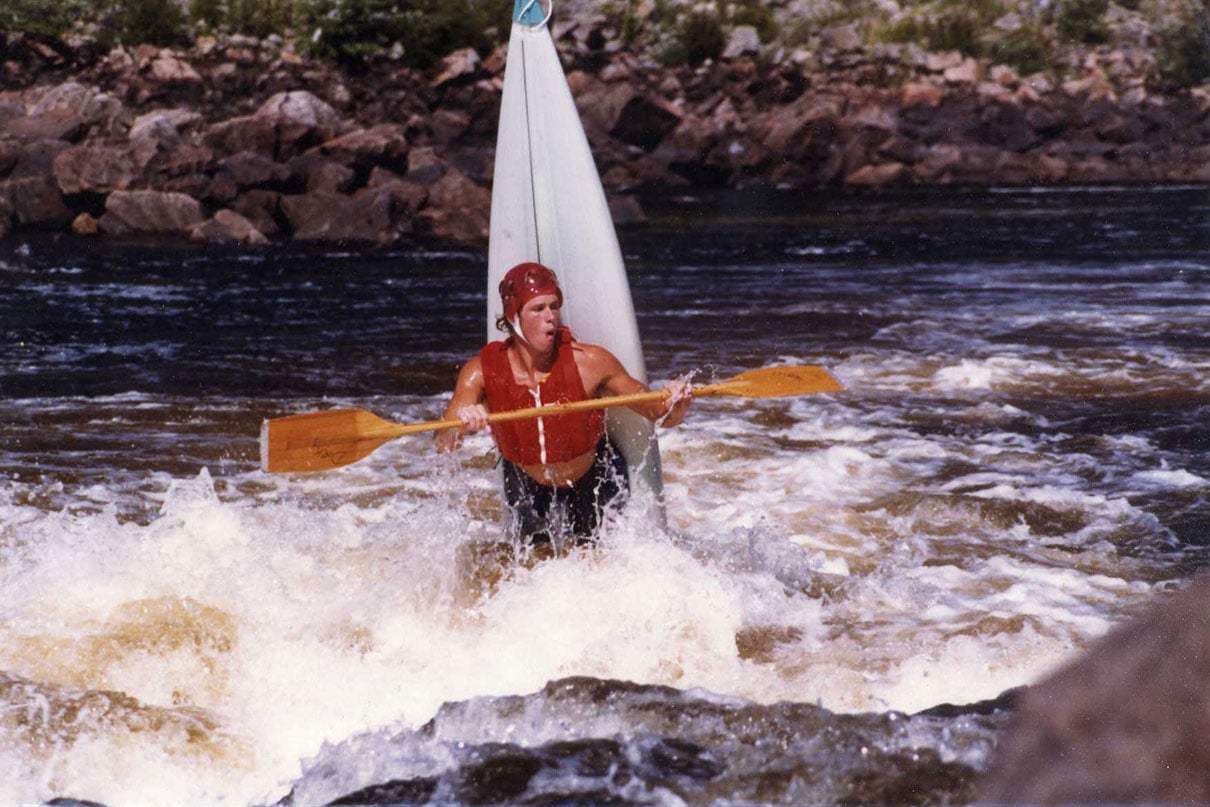

Cyril Derreumaux prepares for Atlantic kayak crossing

Perhaps even more remarkable is the French-born adventurer didn’t start kayaking or canoeing until he was 32 when he moved to California and got hooked on outrigger canoeing. As part of a team, he raced from California’s Newport Beach to Catalina Island, followed by the 32-mile Moloka’i Hoe from Moloka’i to O’ahu. At the time, it felt like an insurmountable distance. “How do I train for six straight hours of paddling?” he remembers thinking.

Then came surfski and canoeing. Still a relative newcomer competing against seasoned pros in the 715-kilometer Yukon River Quest, Derreumaux’s team finished in 45 hours, placing second. With it came a realization: “Maybe long distance is what I really like.”

Rowing was the natural next step. He competed in the 2,400-mile Great Pacific Race from California to Waikiki, Hawaii. His team completed the race in 39 days, earning a Guinness World Record. But for Derreumaux, it also marked what he thought was the end of his long-distance ocean paddling career.

“I loved the experience at sea, but I said, ‘I’ll never do this again. It’s too tough,’” he says.

Yet, something inside him was jolted from its slumber when he read The Pacific Alone, the story of Ed Gillet’s 1987 solo kayak crossing from California to Hawaii in a tandem Necky Tofino.

By the numbers

$80,000: Funds needed to cross the Atlantic.

2.5 mph: Max nautical speed.

3 hours: Average amount of sleep per night at sea.

2 hours: Time Derreumaux had to spend making fresh water daily after his watermaker broke.

91 days, 9 hours: Time it took to kayak from Monterey, California, to Hilo, Hawaii.

2: Number of Guinness World Records Derreumaux holds.

“I was mesmerized,” says Derreumaux.

True to form, Derreumaux wasn’t satisfied with just reading books. He spoke with Scott Donaldson, who was the first person to kayak solo across the Tasman Sea in 2018. Peter Bray—the first person to kayak solo across the Atlantic without sails (paddlingmag.com/0168)—put him in touch with his boat builder, who had retired. Derreumaux convinced the designer to build one last boat; an ocean kayak with a custom-designed pedal system.

He applied this same dogged persistence and systematic approach to prepare for what he knew would be his biggest challenge—paddling without a team. “I’m an extrovert, and I knew it was a mental game, so I tried everything,” he says. His arsenal included the Wim Hof breathing method, working with a coach, hypnosis and yoga.

In 2021, Derreumaux set out amid rough seas and high winds and lost his sea anchor. He was picked up by the U.S. Coast Guard six days later. By 2022, he was ready to try again. He knew his second attempt wouldn’t be smooth sailing but couldn’t have predicted a tropical storm would flood a compartment, causing problems with his batteries and steering lines. His desalinator failed, requiring him to make fresh water manually. And as his time at sea stretched out, so did his rations. Although he’d prepared for 70 days on the water, in the end, it took him 92.

“It was probably the hardest thing I’ve done so far, but I discovered something about myself being alone,” he says. “I want to feel alive. I’ve always found a lot of pleasure in pushing the limits.”

Now 47, Derreumaux’s next expedition is in December, when he will attempt a 3,000-mile solo crossing of the Atlantic from the Canary Islands to Barbados. It will be roughly the same distance as his last, but it will be far from the same journey.

“It will be a different spiritual trip,” he says. Derreumaux is currently raising funds for the expedition on GoFundMe.

Cyril Derreumaux arriving in Hilo, Hawaii, after 92 days, aboard his 23-foot-long kayak Valentine, named after his sister. | Feature photo: Tom Gomes

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.