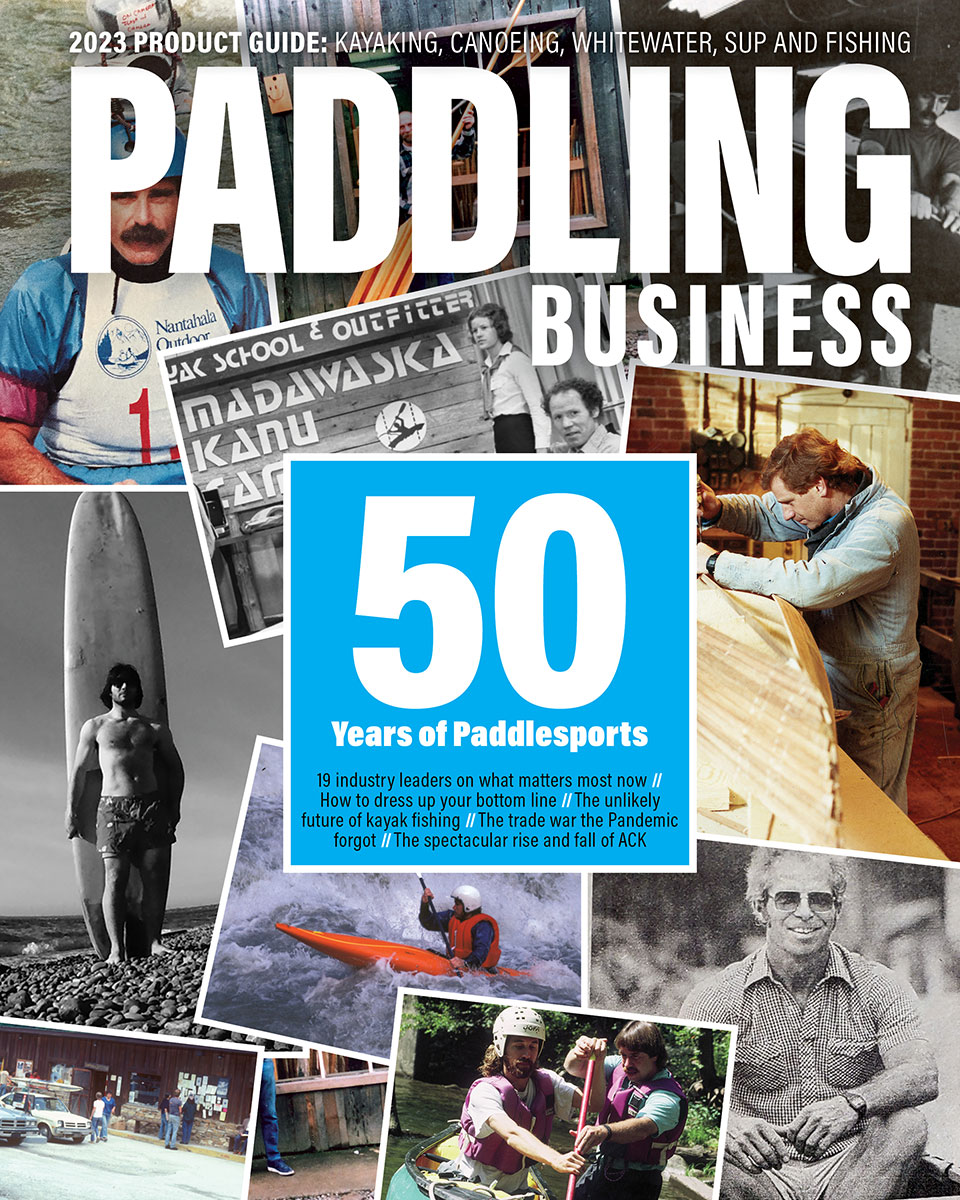

Fifty years ago this summer, paddling was having its moment. A wider outdoor renaissance was underway, and young people who’d tuned into backpacking and other self-powered pursuits also were turning on to paddling. Then, in August 1972 Deliverance debuted on the silver screen, introducing a nationwide audience to the rugged appeal of sleeveless wetsuits and wild rivers, as well as darker themes we wish we could forget.

Looking back at 50 years of paddlesports

Behind the scenes, a handful of pioneer paddling entrepreneurs were busy moving their humble operations from garages and living rooms into honest-to-God factories. Most didn’t have the first idea of how to run a business, and yet many of the companies they launched continue to define the sport 50 years on. While paddling has remade itself a dozen times over and its niches have ebbed and flowed, the industry as a whole is stronger now than ever. So if you had to pinpoint the birth of paddlesports as an industry, it would be 1972.

Tom Johnson traveled to Munich that August as manager of the U.S. Olympic slalom team. Along the way, the L.A. firefighter, coach and part-time inventor stopped at the Tennessee headquarters of a company that had pioneered the art of molding plastic trash cans. Out of that meeting was born the River Chaser, the first rotomolded plastic kayak.

That same year, the first high-performance Royalex canoes came to market. The material had been around since the mid-60s, used for suitcases, a Ford concept car and generic canoe hulls stamped out at the Uniroyal tire factory in Indiana. But paddlers didn’t warm to the material until Blue Hole founders Roy Guinn and Bob Lantz began molding their 17-foot OCA from the stuff. Their motivation? “At first, Bob just wanted a canoe for himself,” Guinn said.

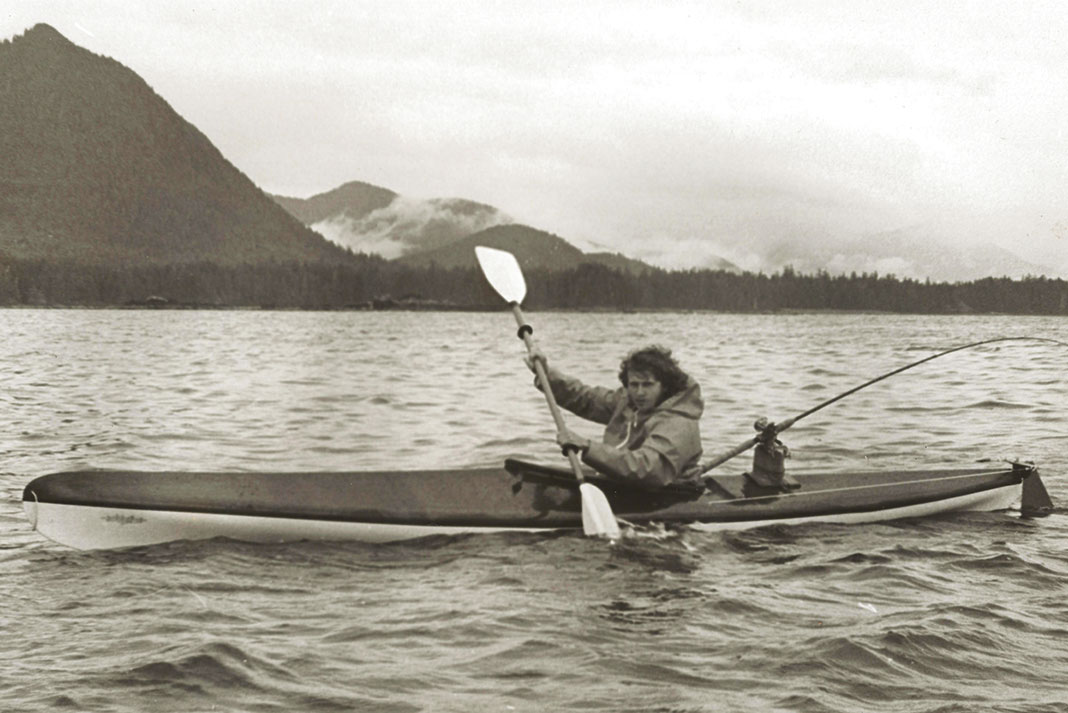

In Southern California, Tim Niemier had long dreamed of a kayak that could punch through ocean surf and make a better platform for diving and fishing than the enclosed sea kayaks of the day. He started in the late 1960s with a seat and footwells carved into an old fiberglass surfboard. By 1972, he was selling along the beaches of Malibu, California some of the first sit-on-top kayaks.

Meanwhile in the U.K., Valley Sea Kayaks founder Frank Goodman modeled his first Anas Acuta kayak from a West Greenland Inuit design. Soon he would begin work on the Nordkapp, which would define the pinnacle of expedition touring kayak design for more than 30 years.

From these deep roots, the paddlesports industry would continue to grow and branch for the next five decades. Paddlesports has lived through boom and through bust, nurtured by passion and the insatiable drive for better kayaks and canoes. Then as now, paddling was an incredibly mixed bag, but the pioneers of every discipline shared the same inspiration—an obsessive love of the sport.

A generation later, when curators from the British Museum described his Nordkapp as the archetypical sea kayak, Goodman thought they were joking. “The Nordkapp was simply a way to do bigger and better trips,” insisted Goodman, who used it on the first kayak expedition to round Cape Horn, in 1977.

Goodman wasn’t the only U.K. kayak maker who was thinking big to go far.

Graham Mackereth founded Pyranha in the family garage in 1971, producing a variety of flatwater, wildwater and slalom racing boats. After Pyranha’s Vedel kayak claimed two top-10 finishes at the slalom world championships, expedition paddler Mike Jones asked for an expedition-worthy version for the 1976 first descent of the river that drains the Everest massif, the Dudh Kosi. In those days before durable plastic kayaks gained widespread acceptance, Mackereth supplied 11 kayaks to the six-person team.

Volume orders aside, building better boats to do bigger trips might not stand the scrutiny of an MBA case study. In the real world of paddlesports, however, it’s proven a remarkably effective business strategy. Valley Sea Kayaks is alive and thriving at 50. So is Mackereth’s Pyranha, at 51.

Go with the flow

For an unscientific analysis of why love of the sport has been an effective strategy, let’s go back to the summer of Deliverance, and the Georgia Tech librarian who moonlighted as a stunt double in the film’s paddling scenes. After the production ended, Payson Kennedy, his wife Aurelia and their friend Horace Holden Sr. took a chance on the Tote & Tarry, a combination gas station and motel on the banks of the Nantahala River in Western North Carolina. Their plan was to build it into a center for paddling and other outdoor pursuits, by tapping the sense of confidence and joy they’d learned to trust on the river.

“When you’re in the flow state, you perform way above your normal ability,” Kennedy explains in a video celebrating the Nantahala Outdoor Center’s 50th year. “I thought that if you could find a job where that happened frequently, where you were often in that state, you’d be happy. You would enjoy it and you would do your best work.”

They refurbished the motel, opened a restaurant and began offering raft excursions and paddling lessons. They hired a handful of river rats and the entire 1972 U.S. women’s Olympic kayak team, then put them to work doing pretty much everything.

“We all cleaned motel rooms, we all worked in the restaurant,” recalls Cathy Kennedy, who was a sophomore in high school when her parents founded NOC. “It was a very group-oriented project.”

Through the years, NOC became an incubator of paddling culture, seeding the Southeast and the world with generations of former guides and paddling entrepreneurs. That pattern repeated itself across North America.

During that same summer of 1972, as the Kennedys carved out their foothold in North Carolina, Canadian paddling champions Christa and Hermann Kerckhoff established a lodge and paddling school on the Madawaska River in the Ottawa Valley. Their daughter Claudia grew up on the river and eventually took the reins with her husband Dirk van Wijk. Now their 30-year-old daughter Stefi van Wijk runs the show, often working with guests who have been coming to MKC since well before she was born.

Through the decades, MKC has changed with its clients, from a program designed to send people to the Olympics to one focused on making lifelong paddlers. The ability to evolve has been key to MKC’s enduring success, and it’s rooted in the sense of community animating staff and clients alike. “As peoples’ wants within the paddling world change over time, if you as a company are centered around people then you can change with them,” van Wijk says.

Van Wijk’s own paddling evolution began over lunch in the MKC dining hall with Wendy Grater, the longtime owner of Black Feather, a wilderness canoe outfitter founded in, you guessed it, 1972. Grater convinced van Wijk to work as an apprentice canoe guide, an experience that taught her to see paddling in a new light. “Instead of a tool for going fast, the canoe became a tool to experience awe,” recalls van Wijk, who was 15 that first summer guiding.

Awe has been Black Feather’s stock-in-trade since Wally Schaber and Chris Harris launched it as a sideline to their Ottawa-based outdoor retail store, Trailhead. Eco-tourism was still in its infancy when Grater started with Black Feather in 1984. Whetherit was sea kayaking in Greenland or exploring new rivers in the Barrenlands, she often found herself guiding something she’d never seen before. Like many paddlesports companies in those days, Black Feather’s business model could best be described as seat-of-the-pants. “We didn’t put a lot of thought into it until someone phoned,” said Grater, who managed a Trailhead store in Toronto in the off-season. “Then we’d go up there and figure it out.”

As the company’s clientele matured, Grater recognized a demand for regular schedules and less-Spartan trips. It was a familiar evolution in paddlesports outfitting. OARS, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2019, made a similar shift and both companies have expanded from strictly paddling trips to offer a variety of bucket list outdoor adventures. Black Feather and OARS also have worked to create opportunities for women, with female guides now filling out more than 35 percent of each company’s roster.

These first river running businesses, founded with purpose and sustained by passion (and often little else) are still seeding the sport with skilled guides and river-stoked newbies half a century on. They were like fuel on the fire, growing and nurturing the sport from its infancy.

If you can’t buy it, make it

It’s hard to imagine in this day of blow-molded box store kayaks, but 50 years ago a paddler couldn’t just buy a kayak. In those days, the most reliable way to get a boat was to make it yourself, preferably with the help of someone who’d done it before you. The result was a cadre of accidental boat makers springing up throughout the paddling community. If they had one thing in common, other than a love of paddling, it was a desire to experiment—a drive to improve the boats they paddled, sometimes by unconventional means.

Tom Derrer founded Eddyline Kayaks in 1971 after building whitewater kayaks for himself and friends for several years in Colorado. Two years later he moved to Seattle and began building touring kayaks designed by Werner Furrer Sr., the patriarch of Werner Paddles.

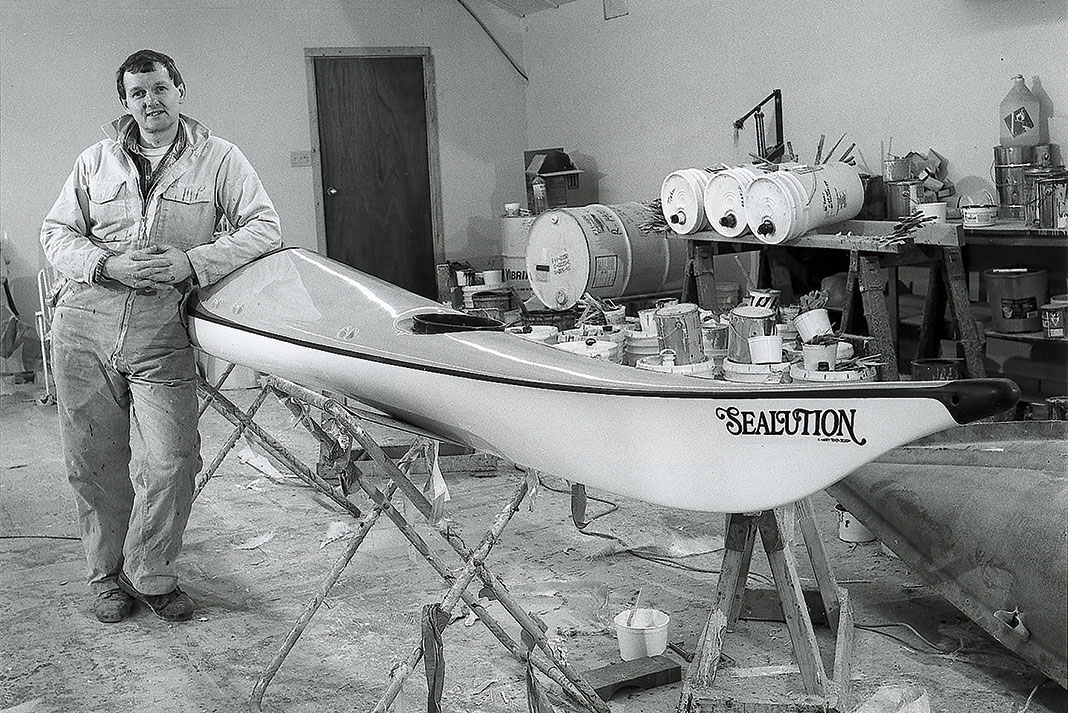

Derrer’s pursuit of better sea kayaks led him to experiment with advanced laminating techniques such as vacuum bagging. Starting in 1994, Derrer began molding kayaks from sheets of high-performance thermoplastic. The technology provided a middle ground for touring boats, somewhere between the rotomolded boats that were beginning to dominate sales volume and the composite sea kayaks that occupied an increasingly narrow niche. Eddyline now molds all its boats from its Carbonlite thermoplastic, and the company celebrated its golden jubilee in 2021 with record sales.

Most didn’t have the first idea of how to run a business, and yet many of the companies they launched continue to define the sport 50 years on.

Furrer, too, began by building kayaks and paddles for family and friends. Werner crafted his first paddle in 1965, and drew up his sales brochure in 1971 for “Werner Furrer Designs” paddles, with fiberglass blades and shafts of Douglas fir. His son Werner Jr. started the business that became Werner Paddles as a way to support his slalom racing, one $17 paddle at a time. It was a family affair from the very beginning. At one point the whole Furrer family was working there, including Werner Sr. and brothers Erich, Werner Jr., and Bruce, who is now the company’s president and sole owner.

Bending Branches was founded 40 years ago in a St. Paul, Minnesota garage, where founders Dale Kicker and Ron Hultman developed the Rockgard canoe tip. The company built its reputation on those reinforced wooden canoe paddles, dabbled briefly in hockey sticks, and found its footing with composite kayak paddles in the late 1990s. In 2008, Bending Branches acquired its top rival, British Columbia-based Aqua Bound. In 2011, Aqua Bound became the first company to market a kayak fishing paddle.

Now the world’s largest specialty paddle maker, Branches owner Ed Vater sold the company in early 2022 to a trio of company veterans he’d brought on board and mentored—competent professionals who love paddling and, in Vater’s words, “would walk through fire” to make the company succeed.

“I could have gotten more by selling it to some outside party, but I never could have lived with myself if some big outfit bought it and hooched it all up,” he says. “I would just be heartbroken.”

Consolidation is just as much a through-line in the history of paddling as innovation, but Vater had no interest in reliving the cautionary tale of Mike Neckar, the Czech-born innovator who shaped some of sea kayaking’s most classic designs while working from a secret lair somewhere in the rainforest of British Columbia, if the legend is to be believed. Necky Kayaks was a leader in both whitewater and touring when Johnson Outdoors acquired it in 1998. Nineteen years later the brand was quietly discontinued “to better align with consumer demand and further build brand equity.”

Johnson attempted to inject the Necky DNA into a new kayak line from its most venerable brand, Old Town. Old Town began making wood and canvas canoes in 1898, riding the sport’s first big boom in the early 20th century and surviving the post-war onslaught of aluminum Grummans. Old Town was also among the first companies to mold canoes in Royalex. An ad campaign of Old Town dropping one from its four-story factory roof did as much for Royalex as the river running exploits of Blue Hole’s legendary OCA.

Johnson Outdoors also acquired Ocean Kayak, the Tim Niemier startup that led the sit-on-top revolution in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He’d been selling fiberglass versions of his Scupper design since the early 1970s, but, to paraphrase a line from Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, young Niemier was convinced the future was in plastics.

By then Tom Johnson’s original Hollowform kayaks had come and gone, replaced in 1982 by Perception’s iconic Dancer, which revolutionized the sport of whitewater kayaking. Perception, by the way, is another product of paddling’s class of ’72. The company can trace its lineage to founder Bill Master’s first kayak, which he built that year in the back of a mortuary. By the mid-1980s, Perception had become the world’s leading maker of rotomolded kayaks, and Niemier approached the company about a plastic version of his Scupper sit-on-top.

“We thought it was interesting, but that real kayaks had decks,” said Dagger founder Joe Pulliam, who was with Perception at the time. “Fortunately, there were other visions of the future of kayaking.”

Niemier went it alone, adding factories in California, New Zealand and France to his original Hawaii facility before selling to Johnson Outdoors in 1997. By then, nearly every kayak manufacturer in the world had at least one sit-on-top in their line.

Pulliam went on to found Dagger, one of a handful of whitewater companies that went head-to-head with Perception through the 1990s. The rivalry drove a whitewater arms race pulling in the likes of Pyranha, Wave Sport and Prijon, and continued after the same corporate buyer snapped up both Perception and Dagger in 1998. The acquisitions were part of an industry wide consolidation eventually bringing the brands under the Confluence umbrella, together with Wilderness Systems, Wave Sport and Mad River Canoe, which was founded in 1971 and brought the first Kevlar canoe to market two years later. Johnson Outdoors assembled a similarly formidable portfolio in the late 1990s.

Paddlesports was growing up, from its roots in the garages and basements of passionate paddler-entrepreneurs into the mature industry we know today. The boats were changing too. Some of that is down to technology; Hobie’s Mirage Drive pedal system may have seemed like a curious anomaly when it was introduced in 1997, but it helped fuel the kayak fishing boom that transformed and reenergized the industry in the aughts, just as whitewater had in the 1990s and standup paddleboarding would in the 2010s. All three injected fresh energy into the industry, backstopped by steady growth in rec kayaking. Put that down to design changes and evolving consumer taste, but there’s also an argument to be made that paddlesports changed because the decision-makers became more distant from the sport.

A person who builds a kayak in his garage is by definition an enthusiast. The boat that person designs will be a paddler’s craft, whether it takes the form of an expedition sea kayak, a cutting-edge whitewater boat or a standup paddleboard. Consolidation gave market research a seat in the design room, which gave us new generations of sit-on-tops, user-friendly rec kayaks with stable hulls and ample cockpits, and generations of battle-ready fishing sleds with pedal drives or, increasingly, electric propulsion.

Fifty years ago, the sport’s pioneers couldn’t have dreamed what paddling would become today—even though many of them guided the first 50 years or so of evolution that brought us all the way to here.

Pride and perseverance

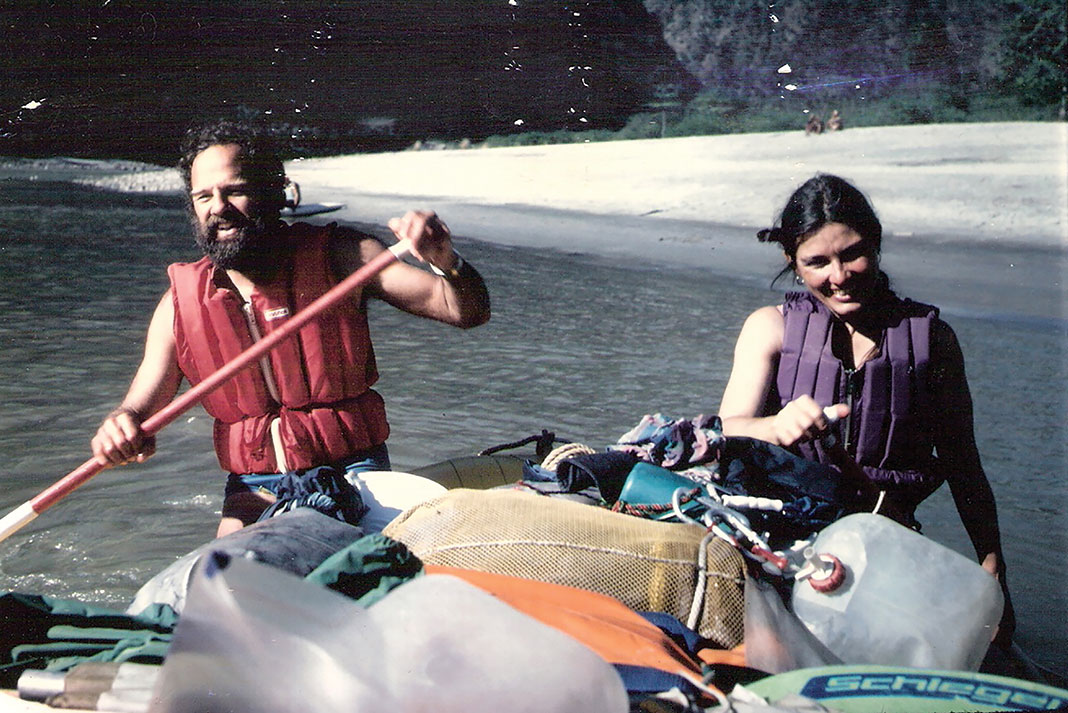

Steve O’Meara founded the outdoor apparel maker Blue Puma in 1971 with two sewing machines in the back of an Arcata, California, backpacking store. Then two things happened. Dan Banducci and Rob Lesser came by to ask about paddling gear for their 1980 descent of the Alsek River, and German shoe giant Puma sued for trademark infringement. O’Meara stitched some of the first proper paddling jackets for the Alsek crew, and later changed the company name to Kokatat.

The name means “into the water” in the language of the indigenous Klamath River people, which fit O’Meara’s new focus on paddlesports and his commitment to keeping production in Arcata. But even with a clear purpose and fresh name, Kokatat almost didn’t make it, and at one point O’Meara put the company up for sale.

“The offer I got was kind of insulting, so I decided I had to turn the company around,” he said.

O’Meara did just that, building Kokatat into a global purveyor of quality paddling apparel. He stayed at the helm for half a century, and sold Kokatat last year to the company’s long-serving director of operations, Mark Loughmiller.

“The offer I got was kind of insulting,

so I decided I had to turn the company around.”— Kokatat founder Steve O’Meara

While it’s tempting to gloss nostalgic about the iconic designs and visionary founders who laid the foundation of the modern paddlesports industry, nobody said it was an easy road. Zac Kauffman and his partners are the fourth owners of Sawyer Paddles and Oars. He says all his predecessors brought the company to the edge and back again. So did Kauffman’s group, which took ownership of the iconic 55-year-old company at the beginning of 2020, just as the Covid pandemic took hold. Orders tanked and then rebounded. The little factory in Talent, Oregon was running at full capacity until the day after Labor Day 2020, when a massive wildfire swept through the Rogue River Valley.

For 24 hours after the forced evacuation, Kauffman didn’t know whether he had a home or a business left standing. Finally someone hiked to high ground and posted a picture of the devastated town on social media, revealing that the flames had stopped 100 yards from his shop walls. With power knocked out across the region, Kauffman’s crew ran the lathes on generators and opened the bay doors to work by daylight.

“It took about a week to get things moving and convincing suppliers that there were still back roads they could use to deliver to us, and how to get through the National Guard checkpoints,” he says. There was no time to waste; the fire had done nothing to quell the insatiable demand of the Covid boom, as Kauffman’s customers politely reminded him. “All our dealers were sending messages, saying, ‘We’re sorry to hear about what you’re going through, but how about my order?’”

The episode shows the industry hasn’t lost any of its resilience in the five decades since it emerged from the basements and garages of paddling-obsessed dreamers. Kauffman’s friend and competitor Ed Vater trusted his company’s legacy to employees who would “walk through fire” to meet orders, and through the Pandemic they had, metaphorically. Kauffman’s team had done so literally, walking through the ashes of their own homes in some cases to do work that matters because it feeds people’s passions.

As we celebrate 50 years of the paddlesports industry, there’s no better sign the future of paddlesports is in good hands.

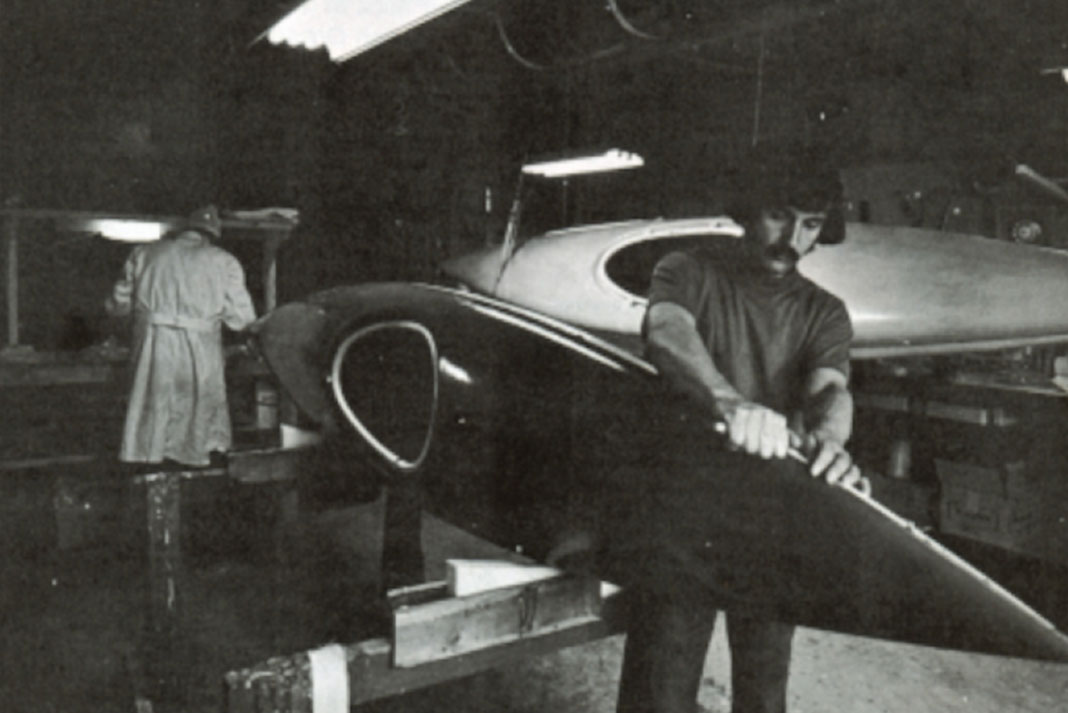

Clockwise from top left: Stefi van Wijk in her vehicle of awe (MKC); Ralph Sawyer (Sawyer); The NOC Store in 1980; Eddyline Kayaks founder Tom Derrer; Bruce Bergstrom thinking big circa 1985 (Sawyer); somebody hold this man’s beer (NOC); Lars Holbek on the Grand Canyon of the Stikine, 1981 (Lesser); Brian Henry; MKC founders Hermann and Christa Kerckhoff; mullets and crossbows will never go out of style (NOC); NOC staffers in their 1972 Olympic uniforms (NOC); Tim Niemier with his original sit-on-top (Niemier).

Don’t forget that 1973 also brought the founding of American Rivers (then American Rivers Conservation Council), without which so many rivers that we hold dear (and sometimes take for granted) would not exist as we know them. Read more about the founding at Americanrivers.org