In his book Gestures, author Roger Axtell has catalogued body language from around the world. He found that similar gestures mean different things depend- ing on where you live. For example, raising your hand and extending your thumb and little finger is the sign for “cool” in hawaii, while in Mexico the same gesture will get you a drink, and in Japan it means the number six. Perhaps with increased globalization lifting your hand in this manner will get you six cold beers at bars around the world. In canoeing, the similar gesture of raising your grip hand shows that you respect the river enough to stay ready to react to anything it might throw at you.

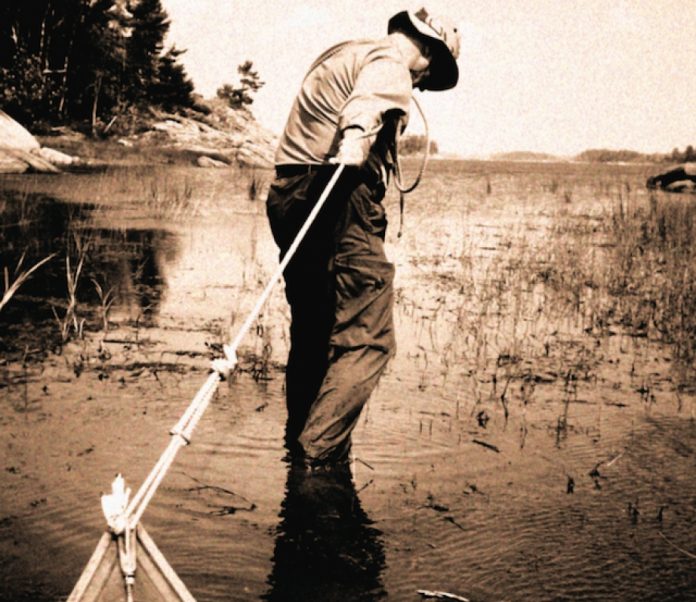

When your grip hand is high, your paddle shaft will be vertical, next to the canoe and close to your knee—right where you want it to be.

Correction strokes are a short reach back to your hip and you need only slice the blade forward to the catch position for a power stroke. If you need a quick righting pry, no problem, your paddle is already at your side and ready for action. With your grip hand held high you can instantly twist your paddle shaft and use the blade as a bow rudder for shifts left and right.

Since most strokes originate with a vertical paddle shaft, there is rarely a reason to drop your grip hand to link different strokes.

A high grip hand will also improve your posture and balance by keeping the paddle shaft and your arms close to your body. With your paddle next to the canoe, you are positioned to rotate at the waist to perform paddle strokes without reaching or leaning. Less leaning means fewer braces and more time for power and correction strokes.

The next time you are on the river, look around at other canoeists who are moving smoothly and appear to be paddling with little effort. You’ll probably see that their grip hand rarely drops down toward the gunwale. Paddlers that do drop their hand often appear to be bobbing their bodies while their boats twitch and lurch awkwardly from one eddy to another. Dropping your grip hand leads to poor paddling posture, a lack of stability and rushed strokes that are executed too late to be effective.

So raise your grip hand to the river. Among canoeists, this gesture will be recognized as the key to linking effective strokes, smooth paddling, great posture and, ultimately, a deep respect for the river.

Andrew Westwood is a regular contributor to Rapid. He’s an open canoe instructor at the Madawaska Kanu Centre and member of team Esquif.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article originally appeared in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Canoeroots.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions