I‘d never cheated in a kayak race before. Come to think of it, I’d never won a kayak race before, either. Now I’d done both in one shot, and it felt pretty good. I’d better explain.

The Great Canadian Kayak Challenge and Festival is the largest purse paddling race in the country. When I was invited to attend the festival, I promised to make the trip to northeastern Ontario but told guy Lamarche, Manager of Tourism, events & communications for the city of Timmins and the passion behind the event, I wouldn’t be racing. I was recovering from both a hernia operation and a bulged disk between my L4 and L5 vertebrae. I hadn’t been in a boat all summer.

It’s hard, however, to say

no to a guy who convinced a blue-collar mining town to throw a kayak party as their premier tourist event.

Every August, the festival brings together arts and culture vendors, a highland dance competition, kayak instruction, a Sunday morning paddle, a triathlon, two nights of free concerts and $20,000 worth of fireworks on the banks of the quietly meandering Mattagami River.

When I arrived Friday night, guy slapped me on the back (ouch!) and told me I was signed up for the celebrity race. he had taken care of my registration. I just needed to find a kayak.

All kayak races begin and end alongside the festival grounds and in front of huge riverside grandstands.

The most physically demanding course is the 35-kilometer elite challenge. somewhere in there is a 100-meter portage— not because it is navigation-

ally necessary, but to make the race more interesting. shorter recreational, novice and youth courses and the easy, three-kilometer celebrity invitational class round out the challenge. All divisions offer huge cash prizes, except the celebrity class.

Bows bobbing behind the starting line, I learned these guys were racing for something more precious than money: bragging rights.

Forget country starlet and Timmins high school girl Shania Twain or the dozens of NHL stars born here. This was a five-year grudge match between Timmins’ real celebrities—the local media and politicians.

Rounding the halfway point,

I was running pretty even with four other boaters: a radio personality for Q92, Timmins Best Rock, a journalist for the Timmins Press, a city councilor and, paddling beside me, the much-loved city mayor. He

told me they all knew who I was, “You’re the ringer kayak magazine editor guy brought

in to mix things up.” He was smiling, but I couldn’t tell if he was joking.

I didn’t feel much like a ringer. I was just happy to find I could sit almost comfortably in a kayak.

Two hundred meters from the finish line conversation ended. It was an all-out horse race. After 3,000 meters and 23 minutes there were only four seconds separating the first four boats across the finish line.

I took the win, but not for very long.

Overhearing two race officials talking at the finish line about the elite division rules, I asked about the other divisions.

The celebrity division, it turned out, limited boat length to 14.4 feet. I would have known this if I’d registered for the race myself, or if the marshals measured the celebrity class boats as they had for the cash divisions.

I’d raced a borrowed kayak that was two feet too long; a speed advantage that could make all the difference. I marched myself to race control and demanded to be disqualified.

The celebrity division title remains where it should, in Timmins. After five years finishing in the top five, local rock and roll DJ Tom Parisi won gold. And in this northern mining town, gold runs in the veins.

Scott MacGregor is the founder and publisher of Adventure Kayak magazine. This year’s Great Canadian Kayak Challenge and Festival takes place in August. thegreatcanadiankayakchallenge.com.

This article originally appeared in the Late Summer/Fall issue of Canoeroots and Family Camping. Read the entire issue on your

This article originally appeared in the Late Summer/Fall issue of Canoeroots and Family Camping. Read the entire issue on your

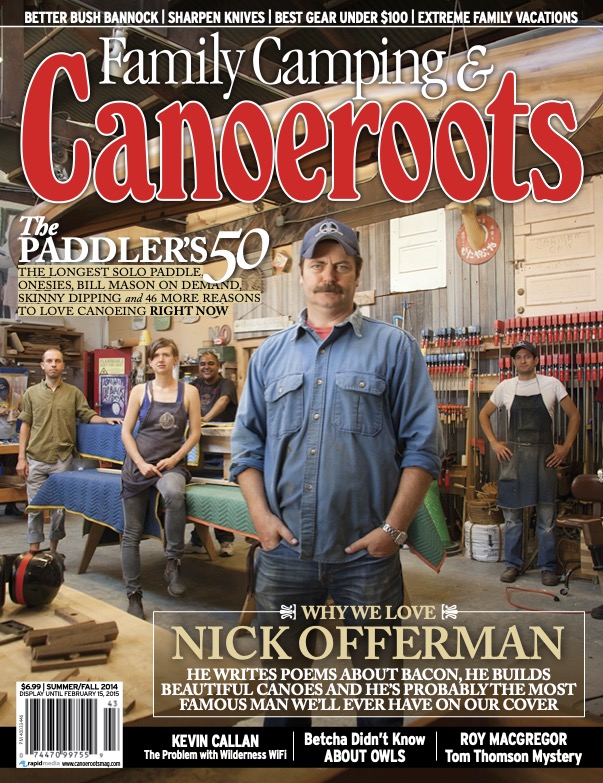

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Summer/Fall 2014.

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Summer/Fall 2014.