Looking for that perfect canoe? To find your match, look at the elements of canoe design—your canoe’s dimensions and hull shape determine how it paddles and whether it’s the right boat for you.

Length, width, and depth are rough indicators of a canoe’s speed, stability, capacity and seaworthiness.

A cross-section will illustrate how the shape of the bottom and sides of the canoe will determine its primary and secondary stability and performance characteristics. A canoe with primary stability is initially very stable, however, if leaned too far, it quickly upsets. Canoes with secondary stability offer better performance and stability while on edge, useful for whitewater and rough-water paddling.

Designed for all-around performance. Maintains a good balance between primary and secondary stability.

Found in specialized racing designs. Great speed and efficiency but very little primary stability.

Flared hull sides help to deflect water, keeping the canoe dry.

A balance between the paddling efficiency of tumblehome and the dryness of flare.

Sides that curve inward toward the gunwales, allowing closer placement of the paddle to the hull.

Canoes that have identical bow and sterns ends. This design offers versatility because it can be paddled solo or tandem.

Now that you’ve got the basics, view all canoes in our Paddling Buyer’s Guide and choose the best one for you.

This article first appeared in the 2009 Early Summer issue of Canoeroots and Family Camping magazine.

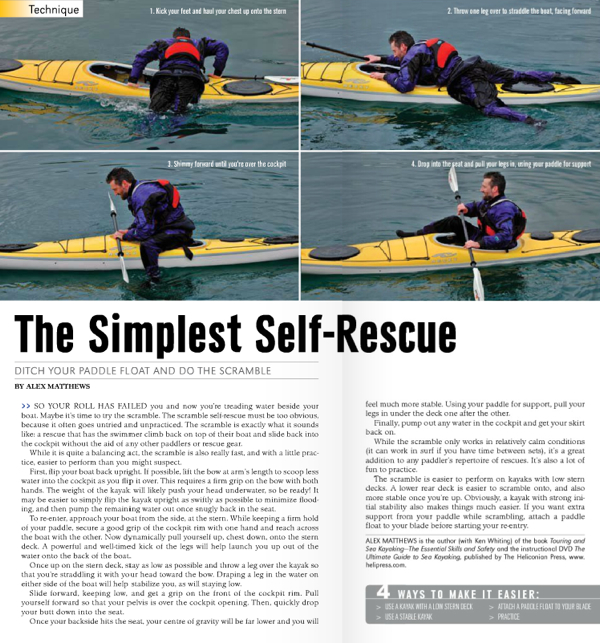

So your roll has failed you and now you are treading water beside your boat. Maybe it’s time to try the scramble. The scramble self-rescue must be too obvious, because it often goes untried and unpracticed. The scramble [aka rodeo, cowboy or cowgirl] is exactly what it sounds like: a rescue that has the swimmer climb back on top of their boat and slide back into the cockpit without the aid of any other paddlers or rescue gear…

This technique feature originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Early Summer 2007. To learn more self-rescue skills, download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or continue reading here for free.

A lawsuit was filed last week against the Yukon Government on behalf of two Yukon First Nations and two Yukon environmental organizations following the government’s controversial decision to open 71 percent of the Peel River watershed to industry development.

The watershed is home to several classic northern river trip dream destinations, including the Wind River, Snake River and Hart River, and the region is one of the last remaining, ecologically-intact wilderness watersheds left in North America, according to experts.

Following a constitutionally mandated process under Yukon land claims agreements and seven years of research and consultation, the Peel Watershed Planning Commission produced a final plan that recommended the permanent protection of 55 percent and interim protection for an additional 25 percent of the 67,500 square kilometer Peel River Watershed.

Although the Commission’s plan is supported by the affected First Nations and has wide public support, on January 21, 2014 the Yukon Government adopted its own unilaterally developed plan for the region, which opens up most of the watershed to roads and industrial development. Yukon Government’s plan leaves 71 percent of the watershed open for mineral staking and industrial development. In the `protected areas` identified by the Yukon Government, which cover just 29 percent of the watershed, all-season roads would be allowed in order to develop existing mining claims.

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Chief Eddie Taylor spoke about what the Peel River Watershed means to his people. “As our elders say, the Peel Watershed is our church, our university and our breadbasket. It sustains our spirit, our minds and our bodies. It is as sacred to us as it was to our ancestors, and as it will be to our grandchildren.”

“The fresh water that the seven rivers of the Peel Watershed provide is by far the most valuable resource within the Peel,” Chief Taylor added.

“Seventy-five per cent of the Yukon is open to mineral staking,” said CPAWS Yukon Executive Director Gill Cracknell. “To compensate for the fragmentation and disturbance resulting from industrial development on the rest of the landscape, we need to set aside large areas for wildlife, cultural uses, tourism and climate change adaptation. The Peel region is one of the last remaining, ecologically-intact wilderness watersheds left in north America. There needs to be real protection, not postage stamp areas riddled with roads and mines.”

Learn what you can do to help protect the Peel with the Yukon Conversation Society.

H2O Performance Paddles is offering a prize of $500 and a brand new paddle to the designer who can come up with a logo for their new line of whitewater products.

Ben Marr is a team ambassador for H2O and he’s giving the contest lots of attention on his personal Facebook page, as well as running the social media campaign for H2O.

“Kayakers often find themselves in situations where gear failure can totally change their situation,” Marr posted to Facebook earlier this week. “My goal with H2O is to not only help produce a high quality paddle that people feel confident using, but work on the aesthetics and style.”

The contest is running until March 31, and three entries have been submitted since it opened on February 1, says Shillion Mongru, the sales and marketing manager at H2O.

“We have a long and loyal fan base,” Mongru says. “We are in the process of re-engineering our whitewater line and wanted to give our paddlers a chance to be part of the process.”

The winning design will be selected by H2O’s staff team and will eventually brand the blades of every whitewater paddle the company offers.

For full contest details and to enter a design, check out H2O Performance Paddles’ Facebook Page.

Learn how to keep your food away from hungry critters with these tips and how-to video from Happy Camper, Kevin Callan.

Meet the Rum Runner by Point 65, the world’s first modular Stand Up Paddleboard (SUP).

Following the success of Swedish manufacturer Point 65’s modular kayaks comes a three-piece SUP, available in two sizes: the Rum Runner 11.5 and Rum Runner 12.5. The Point 65 Rum Runner is an innovative, high-performance, take-apart, touring SUP with a displacement hull, making it a fast, stable, straight-tracking board on which to explore, exercise, and easily take home in the back of your car.

Like the modular kayaks, the Rum Runner features Point 65’s patented Snap-Tap system for ultimate usability both on and off the water. The 11.5’ Rum Runner has a carrying capacity of 265 lbs and weighs 55 lbs assembled. It easily separates into three manageable sections, each weighing as little as 15 lbs, allowing for easy transport in almost any car. Using the longer mid-section, your Rum Runner 11.5 is transformed into a 12.5’ SUP with a carrying capacity of 300 lbs.

The Rum Runner is fast and fun, yet comfortably stable and straight tracking. It is a SUP that snaps apart and reassembles in seconds, making it by far the most easy to carry, rigid SUP. The rotomolded polyethylene construction provides a combination of strength and impact resistance that most other materials can’t match.

Point 65’s Rum Runner features dry storage space with a watertight hatch in the front. The deck is partly covered with a structured EVA foam padding for paddling comfort and grip, and also features D-rings for installation of the optional AIR seat pad. Other features include a retractable fin for shollower draft and easier storage, cupholders, carrying handles on all sections, and scuppers to drain the deck area.

The Rum Runner is in production now and will be widely available at REI, LL Bean and many other retail stores by late winter/early spring 2014.

US MSRP 11.5′ $999

US MSRP 12.5′ $1,099

For detailed specs and to learn more, visit www.point65.com/kategori/5535/modular-sup-new.html

PRESS RELEASE

West Coast manufacturer Eddyline Kayaks has been manufacturing beautifully crafted kayaks in Washington state for over 40 years. Following the release of the Samba three years ago, this spirited compact kayak has enjoyed widespread popularity among smaller paddlers. At just 13’10” and 43 pounds, the Samba is a performance boat in a very managable package. Eddyline’s founders, Tom and Lisa Derrer, shared this new, lovingly filmed video of the Samba. Warning: viewers will experience intense cravings for sunny days on the water!

Also new at Eddyline, the Denali is Tom and Lisa’s response to numerous requests for a larger, lighter, performance oriented kayak with room for the larger paddler. They call this big brother to the Samba, “our little big boat.” It features the same sleek design, but has abundant foot and leg room.