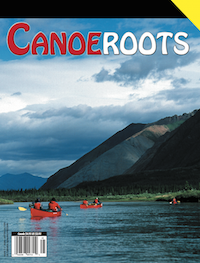

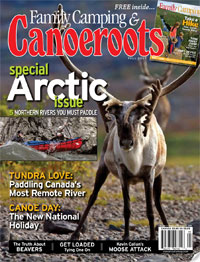

Tundra sunsets that last for hours, wildlife from another epoch,

whitewater coursing through sheer canyons and rock cathedrals

reaching to the sky—if you

haven’t paddled in the north

you owe yourself a trip.

Planning for a northern river trip

can take up to a year, which is why you should start now. We’ve asked five experts which Arctic and

sub-Arctic rivers you have to paddle.

You can take their word for it.

Thelon River

Northwest Territories and Nunavut

The Thelon River sweeps out of spruce-lined valleys into vast treeless barrens. You can paddle for an entire summer under the watchful eyes of lumbering muskox, rocketing gyrfalcons, patrolling grizzlies and vast herds of caribou. This is as close as you can get to primeval Pleistocene wilderness on the planet.

The Thelon’s steady current counters the barrenlands’ relentless east winds. In places the wind and current can pile up big standing waves, but usually the paddling is easy, and the kilometres go by faster than you’d like.

Though the area is now empty of people, signs of ancient human life are everywhere. Dene campsites, inukshuks, burial sites, food caches, tent rings, arrowheads, chipping stations and rock blinds litter the valley’s barren ridges—as if the people who lived on this land just left.

Keep your eyes open

The ruins of the tiny log cabin where John Hornby and his party starved to death in 1927 can be seen on the north side of the Thelon below the junction of the Hanbury River.

Don’t forget

Pack a spotting scope. You can set it up on a tripod and feel like you are on a prehistoric safari at every campsite.

Routes

The stretch from the junction of the Hanbury and Thelon rivers to Beverley Lake should take two weeks and is not challenging. For a trip of three weeks intermediate paddlers can start via the Hanbury, Upper Thelon, Clarke or Elk rivers. All involve some portaging, rapids and canyons. To extend either route allow 10 to 14 days to get from Beverley Lake down to Baker Lake. Between Beverley Lake and Baker Lake there are three very big lakes and some rapids. You should count on becoming wind-bound for a few days here and should be a seasoned Arctic traveller. There are commercial flights out of Baker Lake.

Max Finklestein is the co-author of Paddling the Boreal Forest and author of Paddling a Continent. He is an officer at the Canadian Heritage Rivers System and has paddled the Thelon six times.

South Nahanni River

Northwest Territories

The South Nahanni’s canyons are bigger, longer and more impressive than any other Arctic river I’ve paddled. They have wildly varying characters, from the powerful whitewater of Virginia Falls and Fourth Canyon to the quiet waters and sheer vertical walls of the Gate and towering buttresses of First Canyon. They are magical to paddle through and better to explore on foot.

The whitewater is the real highlight of the Nahanni. If you start your trip at the Moose Ponds in the headwaters of the South Nahanni or the Flat Lakes on the Little Nahanni, you’ll have three days of nearly continuous technical rock gardens that push what can be done with loaded tandem canoes. For experienced whitewater paddlers, it is kilometres of pure fun. The river quickly grows in volume and below the access points at Island Lakes and Rabbittkettle the excitement comes in the form of big waves and increasingly stunning scenery.

Keep an eye out for

Two tufa mounds are a short hike away from the Rabitkettle River. These mounds of sandstone-like calcium carbonate have been built up by hot springs for 10,000 years and are up to 20 metres high.

Don’t forget

A wide-angle camera lense. For a day of the best scenery available to a canoeist you can’t beat the day through First Canyon, starting at Dead Man’s Canyon.

Routes

Most People fly from Fort Simpson into one of five put-in points. For trips of three weeks that start with three days of whitewater put in at the Moose Ponds or the Flat Lakes. The lower access points deliver you to a higher volume river with big waves rather than rock gardens. Outfitters will take people with novice whitewater skills, but the more whitewater experience you have, the more you will enjoy it. From Island Lakes it is three weeks with lots of time for hiking. From Rabitkettle Lake, and the start of Nahanni National Park, it takes two weeks. For the last two days of the trip the South Nahanni leaves the MacKenzie Mountains and meets the Liard River and your pick-up for the three-hour drive back to Fort Simpson.

Mark Scriver has been guiding for Black Feather since 1984. He is the co-author of Thrill of the Paddle and has paddled the South Nahanni, Tatshenshini, Firth, Hess, Horton, Natla, Snake, Mountain, Moisie, Clearwater, Seal and Chuluut Rivers.

Soper River

Baffin Island, Nunavut

The Soper doesn’t just feel like a northern river. It feels distinctly Arctic. Though there are some scrubby willows in the river valley there is no mistaking the fact you are far above the treeline. On top of that, you begin and end the trip in Inuit communities, not Dene communities like most rivers in the Northwest Territories. Seeing polar bear hides stretched out on frames in Kimmirut is a good reminder of where you are.

Despite the remote feel, the river is easy to get to. Paddlers in Eastern Canada can leave home in the morning and be putting up their tent beside the river the same afternoon.

The Soper’s cold waters have cut a U-shaped valley through the flattened peaks that gird the river. The park it flows through, Katannilik Territorial Park, means “place of many waterfalls” and you never go very long between water spouts cascading off the mountains.

The best way to travel the Soper is to allot up to half of each day for side hikes. It only takes an hour to get on top of the ancient rounded mountains to watch the low midnight sun playing on Arctic wildflowers.

Keep an eye out for

While hiking downstream of the Livingstone River confluence, look for small open-pit mines. Semi-precious mica and lapislazuli were mined as recently as the 1970s. Great rock hunting.

Routes

Between Mount Joy and Soper Lake the river doesn’t surpass non-technical class II, except for the easily portaged Soper Falls at Soper Lake. A pace that allows for plenty of hiking will get you down the river in seven days. The season runs from July to late-August. First Air flies from Ottawa to Iqaluit, where you get on a plane that drops into a glacial valley below Mount Joy and touches its tundra tires down on an esker. Finish at Soper Lake, a 15-minute drive from Kimmirut. You can arrange for a shuttle and perhaps dinner with an Inuit family in Kimmirut from the Hunter and Trapper Association. First Air flies out of Kimmirut back to Iqaluit.

Wendy Grater is the owner and director of Black Feather Wilderness Adventures. She has canoed the Tatshenshini, Bonnet Plume, Snake, Firth, Mountain, South Nahanni, Natla-Keele, Coppermine, Hood, Burnside, Seal, Bloodvein and Soper rivers.

Hood River

Nunavut

Any river that Bill Mason liked more than the South Nahanni must be worth paddling. What the Hood has going for it is everything—that is to say it is diverse. There are beautiful lake sections, pounding technical rapids and spectacular falls and canyons. Topping it all is the 60-metre Wilberforce Falls, a two-stage drop that is the highest waterfall above the Arctic Circle.

You don’t have to be a slalom champ to do the Hood, but the rapids are long and can be challenging. You need to be comfortable eddy-hopping down technical sets. Bring good skills and judgment and leave the testosterone behind. But know that you can’t paddle everything. There is no way around a few long, tough portages.

Keep your eyes open

The wildlife is off the charts. Perhaps most impressive are the muskox. You are assured of seeing herds of this seemingly prehistoric beast.

Required skill

Without a reliable back ferry for negotiating long rapids you shouldn’t be on the Hood River.

Routes

Charter a float plane out of Yellowknife to drop you in the headwaters near Lake Tahikafaaluk (make sure the ice is out before you get there). From there it will be a two- to three-week trip down to Bathurst Inlet Lodge and the charter back to Yellowknife.

Cliff Jacobson is the author of more than a dozen books on camping and canoeing. He was married at Wilberforce Falls in 1992.

Coppermine River

Northwest Territories and Nunavut

The Coppermine is an intersection of things geological, biological and cultural.

It takes you on a roller-coaster ride through different rock layers that reveal the meeting of geological epochs.

Above the rock there is a thin layer of soil that seems fragile but somehow supports Lapland rhododendrons that are old enough they might have been brushed by Samuel Hearne’s foot in the 18th century.

The river traverses the dividing line between the treeline and the tundra, which means you get both experiences, and have enough fuel to cook lavishly. More importantly, it crosses the border from the Northwest Territories to Nunavut, and from Dene to Inuit territory. It shows that rivers are bigger than politics.

When you hike to a place of prospect and see the river as it cuts through time and space all these elemental things converge and leave you with a lasting connection to this empty land.

Keep your eyes open

As a warm-up for his real disaster, Sir John Franklin travelled to the Arctic Coast via the Coppermine in 1819, losing 11 of his 20 men. Things were still going well for the party when they hit Rocky Defile, a good place to pull out a copy of Franklin’s Journey to the Polar Sea and read the description of the rapid he named:

“The river here descends for three-quarters of a mile in a deep but narrow and crooked channel…confined between perpendicular cliffs resembling stone walls…. The body of the river pent within this narrow chasm dashed furiously round the projecting rocky columns and discharged itself at the northern extremity in a sheet of foam.”

They ran it, of course.

Don’t forget

Powdered wasabi and dehydrated pickled ginger for fresh Arctic char sushi.

Routes

Charter a float plane drop-off in Point Lake, from where you can speed down the river in two weeks or travel leisurely in three. With the exception of Bloody Falls on the last day the entire high-volume, but not particularly technical, river is usually runnable for paddlers with class III skills.

James Raffan is the author of Bark, Skin and Cedar and has travelled the Coppermine River twice in the summer and once in the winter.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

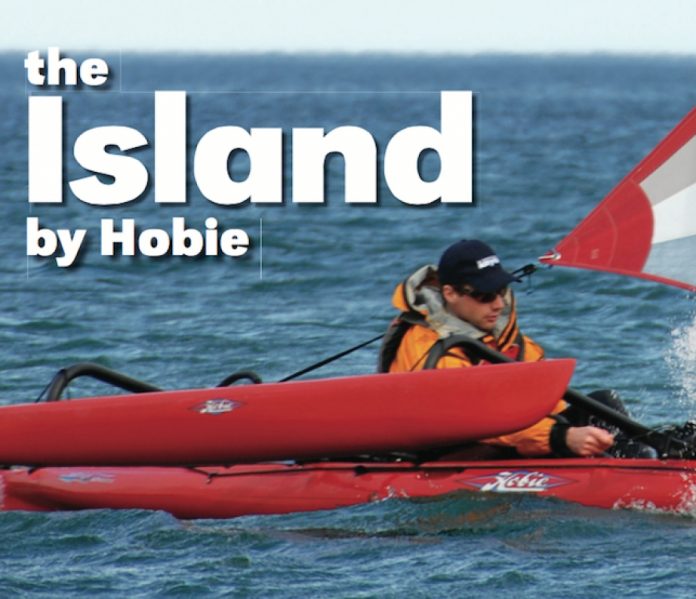

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

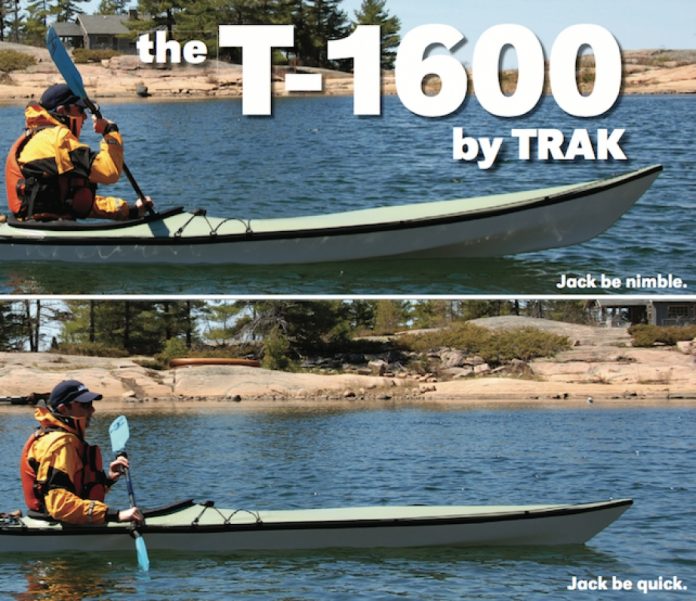

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.