A splashing noise penetrates the tent wall at 5:00 a.m. I ignore it. I want to keep dreaming. With the sky above the thin nylon walls as bright as midday, I know that sleep is impossible so I unzip the fly and poke my head out.

Fifty caribou are crossing the river, heading toward our campsite. A chorus of agitated snorting begins as the lead caribou start pushing their noses further into the stronger current. After some imperceptible signal the herd turns chaotically and heads back to the far side.

Clicking their hooves like tap dancers, they clamber up the cobbled bank and vanish in a thicket of willows where branches mask their antlers and the mats of heather mute the sound of their hooves.

Most people would think this was a pretty exciting wake-up, but today is our 11th day on the Firth River and it’s going to take more than 50 caribou to satisfy me. We have already seen countless caribou milling around in groups this size, but we are after bigger game. Still, my morning mantra per- sists, “Today’s the day,” I say to myself.

Maybe these caribou are the first wave of the much-anticipated migration.

Fetching water for coffee, I’m disappointed to see that the river is still translucent green. In my morning dream thousands upon thousands of hoofed beasts had passed our tents and plunged into the river, crossing in a steady stream that lasted for days, leaving the Firth a soup of hair and dung.

That the coffee will be better without the hair and dung is anemic consolation as I fill the kettle. Time is running out and I’m becoming distressingly obsessed.

We had spent the last 10 days searching— or was it waiting?—for a herd of caribou, though it seems like an understatement to call 123,000 caribou a herd. Every July, the Porcupine herd leaves their calving grounds in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and crosses the Firth River on its return to its summer range in northeastern Alaska and the Yukon.

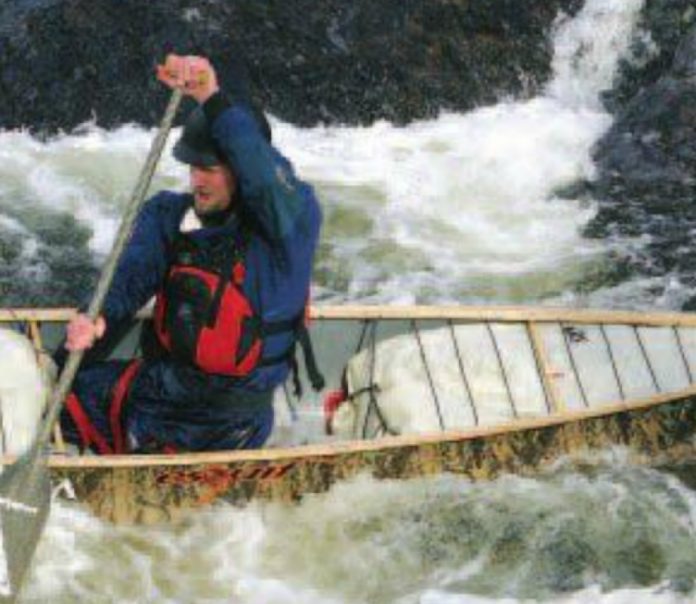

We are four kayakers and two rafters on a mission. Our agenda is to paddle right into the middle of the migration. We want waves of caribou to wash over us, choking us with their collec- tive stench and deafening us with their bleating and snorting.

This sounds like a simple plan. But there is a variable involved, or should I say 123,000 variables. Our research told us the best bet for seeing the herd cross the Firth was during the first week of July—even though there was no way to know exactly when or where this might happen. We had given ourselves 160 kilometres of river and 18 days to work with. So far, our trip has involved more waiting, watching and strategizing about our position than paddling.

The Otter’s tundra tires had touched down at the Margaret Lake put-in on June 28th. While we herded our mound of gear from the plane into raft and kayak-sized piles, a welcoming committee buzzed fiercely around us. After ten minutes the bugs had chased us to a breezy ridge above camp. As irritating as the onslaught was, we couldn’t very well begrudge the bugs their role in the nat- ural cycle. They did, after all, play a lead role in the phenomenon we had come to see.

One reason the caribou travel en masse is to lessen the threat from mosquitoes and warble flies. Warble flies lay their eggs on caribou hair, usually the legs. When the maggots hatch, they burrow under the skin and cut breathing holes. A single caribou can host up to 2,000 maggots, all eating away at the poor weakened beast. These pestilential insect hordes drive the caribou into large herds and chase them from one ridge to another in search of bug-dispelling breezes.

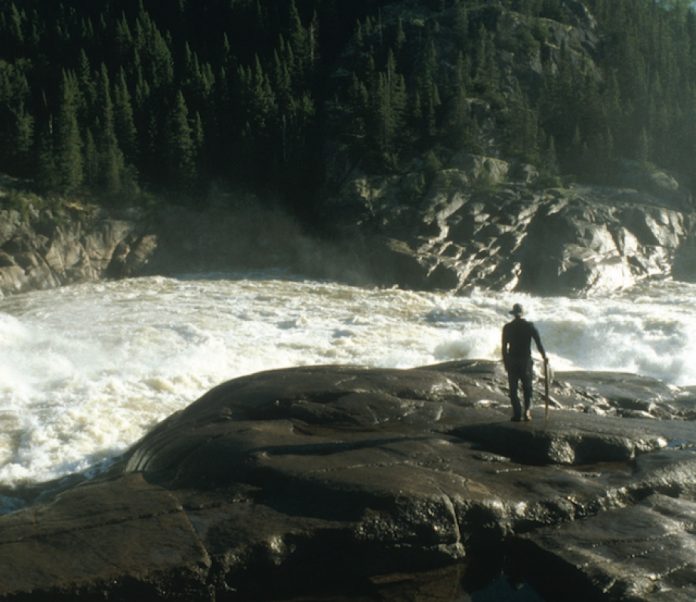

Below us the river, a shiny sliver thread, wove north- ward through the immense open arctic to the Firth Delta. At home in our new surroundings, the rafters, Kevin and Lynn, lounged on the ridge like Zen masters, that is, Zen masters with DEET-soaked veils of netting attached to their hats. Their years of living in Alaska made them comfortable and serene. Being arctic neophytes, Jack and Franz were less serene than excited. Though the grey beards poking through their bug nets suggested rightly that they were both seasoned kayakers, they were awestruck by the vastness of the landscape. Math professor Franz perched on a limestone crag and stared at the panorama in front of us as if he might be able to quantify its vastness.

We launched into a flood of coffee brown water. A recent blizzard had overtaxed the absorbent ability of the spongy tundra. The higher flow and now murky water made it difficult to see submerged rocks and bars so the kayakers paddled ahead of Kevin’s raft to scout.

Cold weather and heavy kayaks made us less playful than usual, but this didn’t translate into more distance covered. Our eyes were more often on the shoreline than the river. We constantly scanned the shore, frequently pulling ashore on cobbled beaches to sleuth for signs of caribou or promising migration valleys. At most we spent three to four hours on the water at a time.

Even though we were unified on our quest, our individual strategies bordered on anarchy. Each of us had his or her own theory about where and when to find the caribou. As soon as we had set up camps at likely caribou crossing points everyone followed his or her own instinct.

Kevin and Lynn would find a likely spot and park there for hours, just watching and waiting. They even spent nights peer- ing like sentries from the shelter of a limestone crag. This placid approach contrasted sharply with that of my husband Jon and myself. We roamed for hours, chased by our own invisible bugs: the need to move. Jon usually dreams up point A to B type expeditions and pursues B like a racehorse with blinders on. It’s a way of travelling that serves him well on his expeditions which have included rowing the Northwest Passage and kayaking around Cape Horn. It’s a little less suited to staying still and waiting for a maddeningly elusive group of animals to stumble upon you. Jon and I spent our days always seeking the next ridge or valley to mark off the next expanse of wild space.

By now, the smell of coffee has woken everyone up and I nestle six steaming cups onto the dryad-covered gravel. It is decision time. Our scheduled pick-up at Nunalik Spit on the delta is a week away. Once we enter the canyon section, five kilometres downstream, we’ll have missed our chance to encounter the herd, the canyon’s steep walls and recirculating rapids make it a place they somehow know to avoid.

All our professed mellowness about seeing the migration has long since vanished like the early morning’s caribou. On our daily forays we had all seen wolves, grizzlies, eagles, Dahl sheep, and moose, not to mention caribou in groups up to a few hundred—but not the surging herd we were seeking. Even though just being in this wild place should be enough, we are dissatisfied and cranky. For all we know, the herd might have crossed the Babbage drainage, hundreds of kilometres from here. During a brief and spirited group meeting, it’s clear that none of us can give up on seeing the migration yet. We agree to wait where we are up to five more days before we race downstream to make our flight.

Now with a definite plan in mind, we worry a little less, and notice a little more. Jon and I paddle across the river the next morning to explore the valley where the previous day’s indecisive caribou had disappeared. We follow a sinuous ridge that affords good views of two valleys.

While Jon snaps photos, I wander down the ridge a little and glass the valley below. Something streaks into view and I focus in on a wolf stalking a nearby cow and calf. The binoculars can’t encompass both the wolf and the caribou, so I stay glued on the wolf. I hear the caribou getting closer. My heart pounds in my ears, but I hold the glasses steady; I know that soon all three players will meet. Half of me wants to jump up and scream, “Watch Out!” But the predator in me whispers, “Keep it cool, wolf, they’re almost close enough.” When the cow and calf finally enter into view, the wolf leaps from his crouch and bolts toward the caribou.

The wolf’s burst of speed puts him within a few dozen metres of his prey, but after 30 seconds the caribou widen the gap. The wolf pulls up and slinks downhill while the caribou rush up the ridge. The wolf has played the surprise card as well as possible, but the caribou hold all the speed cards.

There was no gory finale, but every hair on the back of my neck is standing at attention. Witnessing this predator-prey encounter—one that’s incredibly intense but entirely commonplace—brings my perspective down to tundra level and I realize that experiencing the caribou migration is something that is more complex than blocking a few days off on a calendar.

Below me the tundra in either valley is dotted with small groups of caribou milling around like spiral galaxies. Now, instead of looking for a herd that isn’t there, I see individual animals acting out their individual roles in the age-old drama of survival.

Being so focused on one huge herd had blinded me. The small groups we had been watching for days were the migra- tion. The wet and cold weather that had pinned us down the first week had also kept the insect population low enough for the herd to saunter along in small groups instead of one tight wave.

But the realization that I won’t be paddling through a river choked with caribou isn’t disappointing. Instead, it’s accompanied by an appreciation for the way everything in this austere environment is interconnected.

We were wrong to just focus on the caribou; we should have been looking at the entire arctic ecosystem. The caribou were migrating, as they always do, according to a mix of internal and external forces. Caribou spend their lives eating, avoiding predators, and reproducing. After calving, they group together in response to the insects and instinctively head for areas that offer good foraging and cool, humid conditions. Once together, they have to keep moving or they’ll exhaust the food supply.

It all fits neatly into place, with or without an ultimate explanation. Biologists have theories about why caribou migrate when and where they do, but no one really knows how it is that tens of thousands of animals get together and move as one.

Our group, on the other hand, was driven not by instinct but by curiosity. Psychologists also have theories about human behaviour, but no one can really explain why Jon and I are driv- en, intent on always reaching a destination while Kevin and Lynn are content to sit, and watch, and wait.

On this day above the Firth I see that, with or without expla- nations, our group functioned more like the small groups of caribou that we encountered rather than the tight-knit one we sought—and that we too had reached our destination.

Christine Seashore divides her time between British Columbia and Montana.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

The Impex name is said to derive from “import-export,” adopted when Mid-Canada Fiberglass was looking for a U.S. tag for

The Impex name is said to derive from “import-export,” adopted when Mid-Canada Fiberglass was looking for a U.S. tag for

This article was first published in the Spring 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine.