The outdoor play in northwestern B.C. is neverending. In 2001, filmmaker Dustin Knapp came with a crew to Terrace, B.C., chasing rumours of an untouched whitewater mecca. Dustin passed the word on to his bro Brandon about the area’s huge number of unrun rivers and falls. And last September, Brandon Knapp showed up in my living room at 2 a.m. with a whole crew from Teton Gravity Research. They were looking for first Ds and unique never-before-filmed rapids and falls to feature in the up-and- coming New Rider Productions movie Wehyakin. And they were looking for a place to sleep.

Our house is 980-square-foot two-bedroom. I had talked to Team Dagger paddler Scott Feindel about coming up to paddle and offered him a place to stay. Well, in the morning I woke up to people everywhere, eight in total—in the mud room, kitchen, spare room—and my wife Suki was going nuts. There was Brandon, Scott, TGR regular Seth Warren, Dagger bad boy Corey Boux, Riot rep Matt Rusher, NRP film jockeys Trask McFarland and Loren Moulton and photographer Ryan Creary.

“Shane and Suki, who hadn’t met any of us before, awoke to 10 people scattered all over their home,” Creary said. “Then Corey clogged the toilet and chaos ensued from there.”

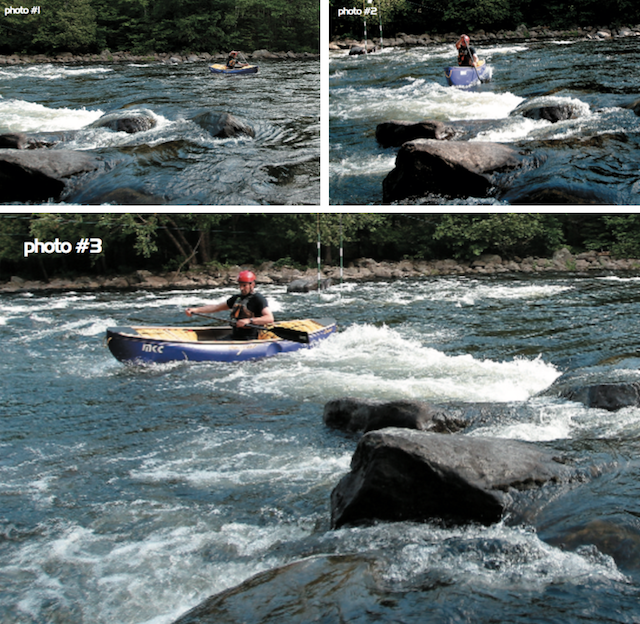

Iknow I will live in Terrace for years to come because there is so much to do. Hundreds of creeks, rivers, waterfalls, logging access roads, huge run- offs and a paddling season that extends from April to late October combine to make this region a whitewater paddler’s dream.

Over the years the development of logging roads has opened the door for kayakers seeking new rivers; every year new roads and bridges are built, potentially opening up the next classic run. Most of the current put-ins and takeouts are at bridges, which makes things nice because bushwhacking in northern B.C can be hell.

NORTHERN BC’S NUMEROUS FIRST DESCENTS

Over the past decade, paddlers from the region have been gradually ticking numerous first descents. Local kayakers can testify that the only dilemma is not finding the virgin runs, but deciding which one to tackle first. And with a relatively small paddling community, the harder runs only see one or two descents a season.

Always ready to get in a few days on the river with strong boaters, I was pumped to show these guys around. Starting in Terrace we ticked the class V classics—Willams, Kelanze, Kalum, Kitnayakwa, and the second descent of Wesach Falls, a 63-foot waterfall 35 kilometres north of Terrace. Everyone ran it. It’s the easiest falls ever—line it up and tuck. You’re more likely to get into trouble at the put-in.

“I seal launched in and skipped across the river and nailed the wall which bounced me into this hole,” Boux said. “There I was 25 feet from the lip of the 63-foot drop, doing unintentional loops. I finally broke free of the hole and gained my composure as I floated to the lip of the falls.”

Later, we pushed on to some of the runs I have been looking at for the past few years. I was impressed by the precision of these guys’ basic river moves, especially with Brandon. Not having to worry about them screwing up the line, the stress level was way lower for me even though we paddled some sick stuff.

We rented an ocean boat and headed down the coast to Kitimat, a small industrial port town 55 kilometres from Terrace. Our day on the ocean boat proved to be a good value with two first descents including Jesse Falls. The falls makes up the shortest river in the world. So a fisherman told me—fishermen are a good resource in northern B.C. Jesse falls is an astounding coastal waterfall that cascades 50 feet out of an alpine lake, dumping you directly into a deep-sea harbor. We ran the falls and stopped at a natural hot spring on the way home.

Back at base camp, things settled down after awhile. Suki calmed down and the guys were rad, cleaning and cooking every night! After their two-week stay they bought us a DVD player, helping us enter into the 21st century.

Shane & Suki Spencer own and operate Azad Adventures, an outdoor guiding, instruction and retail business in Terrace, B.C.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions