One of the greatest benefits of canoe camping is the way it brings us closer to nature. But when it comes to bears, keeping a safe and respectful distance away is better for all involved. Unfortunately, drawn by food or familiarity, the bears themselves may have a different plan. Read on for expert tips to help avoid a problem bear encounter, plus what to do if an ursine intruder does decide to show up for lunch.

Two tales of bad news bears in camp

French River bear encounter

Friends Louis Poulin and Dan Mailhot were on a canoe and kayak trip on the French River in Ontario, Canada. The pair arrived at an island campsite on their second day and found it strewn with food scraps and abandoned camping gear. Someone had written “BIG BEAR” in cinder on a rock. Bear scat found on the campsite seemed old, but the food appeared fresh. The scene was ominous enough to convince Louis and Dan to find another campsite.

On the new site, Dan used a bear-proof Ursack stuff sack and a small bear-resistant canister to store his food away from their sleeping area, while Louis left his in the airtight hatch of his kayak overnight. Around midnight, Dan heard rustling in camp and soon after a black bear ripped into his tent hammock near his head. Dan yelled and both he and Louis got up and realized the bear had also gone through Louis’ gear, none of which had been in contact with food. With the bear still in camp, the pair banged pots and pans but were unable to scare the bear away. They hastily paddled off in the dark to a distant rocky islet, where they huddled in sleeping bags for the rest of the night.

They returned in the morning to assess the damage and collect their gear. The food canister was untouched, but the Ursack, which Dan had tied to a sapling, was gone. With a duct tape patch on Dan’s hammock and what food was left, they were able to salvage the remainder of their trip.

Algonquin bear encounter

Julia and Chris Prouse chose an easy route in Algonquin Provincial Park for their eight-month-old son Cedar’s first overnight canoe trip. They made the portage from Canoe Lake to Joe Lake, where they had reserved a campsite, on a drizzly afternoon.

Arriving at their site, they were disappointed to find food packaging in the firepit, left behind by previous campers. They tidied up the mess and made camp for the night. That evening while Julia was preparing dinner, a black bear came into camp and attempted to investigate their open food barrel. Julia yelled to scare the bear off and it responded by chomping and clacking its jaws, especially when Julia came between it and the barrel. The bear came within two meters of her and Julia gave it a “light tap” of bear spray, which caused it to disappear into the woods.

Julia and Chris faced a tough decision. Daylight was fading and they weren’t comfortable with night paddling. They considered paddling to a nearby site, but had heard air horns and yelling from across the lake, indicating their neighbors were also dealing with an unwanted visitor. They had plenty of bear spray, so they chose to spend the night. They hung their food barrel using the cable and pulley system provided by the Park and wondered if the bear would return. Sure enough, it did. The couple could do little but listen to the bear tearing into the barrel as they spent a sleepless night.

In the morning, they found the barrel still suspended overhead without its lid. The bear had opened the clasp and dumped the contents, consuming much of their food. The couple cleaned up the mess before breaking camp and paddling out to Canoe Lake.

5 tips to avoid problem bear encounters

Both groups were clearly dealing with a “food conditioned bear,” says Kim Titchener, a wildlife professional in Banff, Alberta and creator of RecSafe With Wildlife, an online community she launched to minimize impacts to wildlife as interest in the outdoors surged during the Pandemic. When a black bear successfully raids campsites the behavior becomes habitual and there’s little campers can do to break the pattern, Titchener says. This is concerning because 40 percent of fatal bear attacks involve animals familiar with human food. Following are the lessons she says we can learn from both stories.

1 Avoid problem areas

Popular canoe routes are often plagued by repeat offender bears. Scan Facebook groups and talk to park staff before you go. If your research uncovers tales of problem bears, “do you really want to go camping there?” asks Titchener. “I would consider a different route.”

2 Camp survey

Look for bear attractants like food waste, evidence bears have been feeding in the area (such as scat), and signs of carrion (look for birds circling overhead) when selecting a campsite. If your survey reveals any of these red flags, Titchener suggests cleaning up the mess and moving to another campsite if other options exist.

3 Bear-proof your food

Food barrels and kayak hatches are not bear-proof. Titchener ranks metal lockers, Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee-certified containers like canisters and reinforced stuff sacks secured to a large tree as best for food storage in camp. But lockers are uncommon and approved canisters and stuff sacks are small. The next best option is hanging your food (in a pack or barrel) at least four meters from the ground, 1.3 meters from adjacent trees and 100 meters away from your tent. If suitable trees aren’t available, stash your food pack or barrel as far away from the campsite as possible. Storing your food in a canoe that’s anchored in deep water, far offshore is another option when the conditions are right.

4 What to do if…a bear comes into your campsite

With black bears, keep your group together, make yourself big and create a lot of noise. Titchener recommends a tactical high-powered flashlight for night encounters. Bear spray is highly effective—but only if you’re carrying it in an accessible location.

5 What to do if…the bear returns or won’t go away

Hanging your food far from camp should keep a marauding bear far from your sleeping area. But if a bear breaks into your tent, Titchener says it’s time to leave the campsite. Be sure to inform park or wildlife officials about your experience.

“You look down, they know you’re lying and up, they know you don’t know the truth. Don’t use seven words when four will do. Don’t shift your weight, look always at your mark but don’t stare, be specific but not memorable, be funny but don’t make him laugh. He’s got to like you then forget you the moment you’ve left his side. And for God’s sake, whatever you do, don’t, under any circumstances…” —Rusty to Linus, Ocean’s Eleven. | Feature photo: Follow Me North Photography

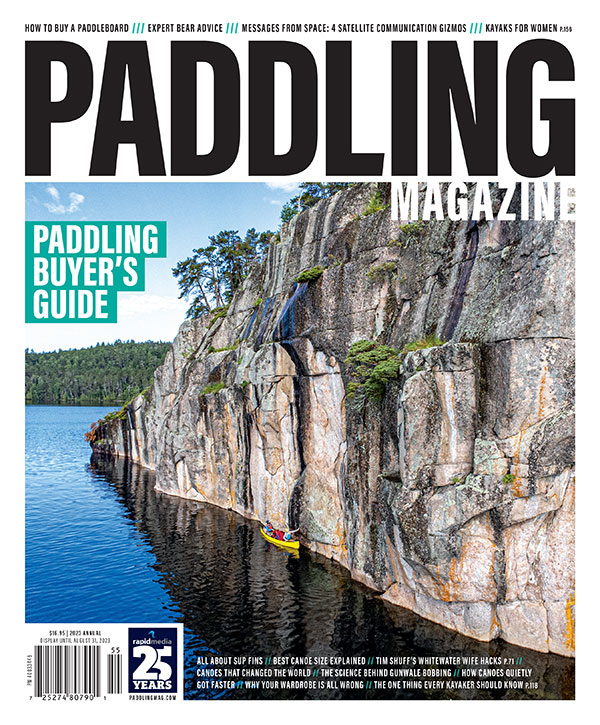

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

C’mon now–hang your food 100 meters from your camp? Really? If this is the thick Ontario bush, most people will get lost trying to find that hanging tree. And of course, black bears climb trees–really well. All you’re doing here is separating humans from food, knowing full well the bears will get your food. As to anchoring a food-filled canoe filled in deep water off shore–get real: not with my $3,000 canoe! Yeah, so at night the wind comes up and the waves break your anchor and smash your canoe on the rocks. Great job–at least the bear didn’t get your food! I agree with most of the other recommendations though, especially, the high intensity flashlight which, around midnight, I once used to send a Saskatchewan bear (Cree River) running. Works great on wild cats and dogs too.

Ursacks don’t actually work. I’ve had a bear chew through one while I was out for a hike near Pine Creek CA. The website claims they can handle 60 minutes of bear breach attacks which means you have to get up to defend it, which basically means it doesn’t work. Check out the REI reviews to see many pictures of shredded ursacks. It’s frustrating that this product still exists and is even carried by REI.