Shane McManus reckons he’s run Big Splat on the Lower Big Sandy 500 times. Almost every time he runs the West Virginia classic, he sends the signature class V waterfall three times—once for himself, once for his best friend who moved out of state, and once more to lead others down.

No one knows Big Splat better than McManus, but if you roll the dice often enough, eventually they come up snake eyes.

Accident debrief: Inside a veteran boater’s scary swim

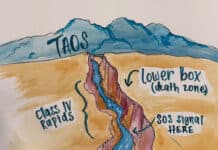

Such was the case on December 18, 2024, when the 36-year-old Morgantown, West Virginia, boater met friends for an after-work lap on the Lower Big Sandy. They were an experienced crew of paddlers spanning three generations, from 19-year-old up-and-comer James Malek to Jim Murtha, who, at 72, is still a regular on the Upper Yough. Josh Martin, 40, had run the Lower Big Sandy about 50 times, but always portaged Big Splat. A self-described conservative boater, Martin had so far chosen not to tackle the tricky and consequential class V drop, which features a technical lead-in, an undercut cave on river right, and a seemingly magnetic piton rock at the bottom.

During the shuttle though, Martin told the crew today might be the day.

“We get on the river, and everything was crisp and just really good lines the whole way down,” says Martin, a U.S. Army sergeant with three combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

By the time they reached Big Splat after two miles of fun class III-IV and a clean huck of 18-foot Wonder Falls, a plan was in place: McManus would make his customary first run, then hike back up to lead Martin down in Blue Angel formation, with Malek following in sweep position. Murtha and a fifth boater, John Rooke, set safety on the so-called seal-launch rock overlooking the main drop on river left.

While the 16-foot plunge gives Big Splat its name and reputation, the ledge drop just above is nothing to be trifled with. Here the river funnels right into a nasty horseshoe hole, requiring a hard-driving boof into a river-left pool a couple of dozen feet above the main drop. This is where McManus pulled his paddle a little too far past his hip and it caught, pulling him off balance. In hindsight, he thinks he could have stayed upright with a hard brace, but in the moment, he opted for a quick back deck roll. As he attempted the roll, his hip slipped out of his outfitting, robbing him of the leverage he needed to roll up. As this was happening, he felt the horseshoe hole pull him in and then flush him downstream.

When he felt himself slam into the guard rock immediately above the big drop, McManus knew exactly where he was heading, and the grip of the swift current confirmed the worst.

“I felt myself speeding up, and then I just felt myself drop—boom!—into this stern piton, and I felt this crack happen all the way up my body,” he says. “Just everything popped in all these different ways.”

Rescuers spring into action

From the seal launch rock on river left, Murtha and Rooke watched McManus’ kayak disappear into the drop’s deepest seam and stay down. They knew he hadn’t had a breath since flipping in the entrance. Murtha couldn’t get a rope to McManus from where he was standing, so he began to count off the seconds. Had he reached 180, Murtha said later, the team would have to slow down and reassess the situation.

Martin hadn’t seen McManus go over—the horizon line blocked his view—and he caught the eddy above the main drop as planned. Meanwhile, Malek, who had seen everything, shot past toward the lip.

Suddenly Martin, who moments before had been comfortably flanked by experienced paddlers, found himself alone in the middle of a consequential drop he’d chosen prudently to avoid for years—with Rooke hollering that McManus had gone over the falls, upside down.

“When I heard that, it was like, ‘All right, I’ve gotta run this drop,’” Martin says. “I gotta go get my friend.”

The feeling took him back to the firefights he’d experienced in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. So much was the same—the adrenaline dump, the reliance on others, and the stark recognition lives depend on you playing your part under extreme stress.

“I’ve said this a lot over the years. Whitewater kayaking is the closest thing to combat, because it’s your ability to act under pressure that determines the outcome of the event,” he says. “If you tuck your head between your legs in a firefight, things are going to get worse. Do something to improve your outcome, and things will get better.”

Martin immediately peeled out, hard on the heels of Malek, who had adjusted his launch angle to avoid the possibility of hitting McManus, landed in a seam, and flipped.

“I roll up, and for probably five, 10, 15, 20 seconds, I don’t see him,” Malek says. “So I’m trying to get to a spot where I can get out and get a rope to him because I know under and behind the curtain is super undercut.” Just then, Martin landed cleanly next to Malek, and both boaters saw McManus come to the surface.

“I see him pop out without a helmet or any of his gear. He had his life jacket on, thank God, but helmet, boat, paddle, shoes—they’re all gone,” says Malek, who towed McManus to a nearby rock where he lay splayed out, regaining his breath. By Murtha’s count, he’d been underwater for well over a minute.

Malek, an EMT studying nursing at West Virginia University in Morgantown, performed a quick assessment of his friend. “I checked his airway, breathing and circulation. He was breathing all right and I didn’t see any bleeding. So those three things tell me this is not going to be a 9-1-1 where we need to get evacuated with a helicopter,” Malek says.

He asked McManus what he needed.

“Get my boat,” was the reply.

Martin had already recovered McManus’ helmet, and Rooke soon emerged from downstream with his well-loved Rivrstyx paddle. Rooke then produced a short NRS strap to stand in for the broken helmet strap. As McManus regained his senses, Rooke peppered him with cognitive questions: “What’s your birthday? Who’s your fiancé? Where are we?”

“I’ve said this a lot over the years. Whitewater kayaking is the closest thing to combat because it’s your ability to act under pressure that determines the outcome of the event.”

—Josh Martin

McManus was safe for the time being, and the crew next faced the consequential decision of how to get him out. Though he aced the cognitive tests, McManus’ vision was blurry in his left eye, suggesting a concussion, and the pain in his chest and snapping sounds on impact meant he’d likely cracked or even broken some ribs. In fact, he’d broken 10 ribs (four left, six right) and his L2 vertebra, on top of a wicked concussion.

McManus could stand and walk only with difficulty and the hike out was about two miles of rugged terrain. After a short discussion, Martin voiced his opinion: “Hey folks, I think the fastest way out of here is down. Even if we portage every rapid, it’s still faster.” The group nodded their assent and started the three-mile paddle out.

They traveled in close formation, with Malek leading, Murtha and Rooke flanking McManus, and Martin running sweep. McManus walked class IV First Island using a pair of paddles like crutches and paddled the rest of the way using what Malek called “little ducky strokes” to avoid twisting his damaged torso.

“The paddle out, let me tell you, you’ve never been part of something more eerie than that,” Martin recalls. “No one said a word other than to ask Shane how he was. No one boofed, no one surfed—it was just paddle the raft lines to the bottom of each rapid, ask Shane how he is, and then continue.”

After the last named rapid, Malek sprinted ahead to get his car warm and ready. The temperature was in the high 30s or low 40s, and though McManus was wearing a drysuit and layers he’d also endured a long swim and significant trauma. Maintaining his body temperature and getting him to a hospital as soon as possible was essential. As Martin and Malek helped their friend into the car, they compared notes on the information they would convey to the medical team. With their shared backgrounds in emergency medical care—Martin is also an EMT and teaches search and extraction at the Army’s premier disaster response school—Martin and Malek knew how important this handoff would be. Malek drove straight to Ruby Hospital in Morgantown, where a trauma team got to work.

Reflecting on a run gone wrong

Eight weeks later, McManus is well on the way to a full recovery, but the fact he ended a routine after-work run in a hospital bed says a lot about the nature of river running. Whitewater doesn’t feel like much of a team sport on those blue-sky days when you can’t place a stroke wrong, and the only help you need is someone to drive shuttle. But in ways that truly matter, whitewater forges deep bonds, tempered by the joy we experience, the accomplishments we share, and, occasionally, the unbearable stress of life and death hanging in the balance.

In a description of the accident, Malek wrote the moral of the story is anything can happen on class V, even to people who have run a rapid hundreds of times at every level. Surely that’s true. But the corollary is it’s up to each of us—whether we paddle class II or class V—to develop the skills to play our part when things do go sideways.

There’s no greater expression of teamwork than having the skills and composure to hold your end of such a bargain. We should ask nothing less of ourselves and can ask nothing more from those we paddle with. That natural back and forth is why McManus takes an extra lap on Big Splat for his friend who can’t be there. It’s the reason he mentors Malek in small ways and shows up to roll sessions with a smile.

Anyone who knows McManus will tell you he gives more on the river than he asks, but the fact help was there for him when he needed it most speaks to the beauty of our sport—an element that goes beyond the joy we share on the river and the beautiful places it takes us.

Jeff Moag is the former editor of Canoe & Kayak magazine. Debrief is a new column, deconstructing paddling accidents and the lessons we learn from them.

Shane McManus running Big Splat on the Lower Big Sandy in 2022. | Feature photo: Justin Harris

This article was first published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.