“What do you do when a polar bear charges you? We found yelling colorful language was more effective than gentle talking,” Arctic kayaker Jon Turk explained after a 104-day circumnavigation of Canada’s Ellesmere Island in 2011. “The right tone could communicate, ‘You’re bad. We’re just as bad.’”

After a second white bear over-lingered near Turk and expedition partner Erik Boomer’s tent, Jon texted his wife: “Bears scare us. We scare bears. Wind scares us. We do not scare wind.” Along with gale force headwinds, unstable ice and breaching 2,000-pound walrus were a constant threat.

Completing the 1,485-mile odyssey around the world’s tenth-largest landmass was a crowning achievement in a life of pushing limits in cold and remote climates, primarily by sea kayak. Yet two days after completion, normally a time of recovery and reward, Turk’s life was threatened again. Sudden onset renal failure triggered a descent into metabolic shock, fatal without immediate treatment. The trauma coincided with three days of bad weather, delaying his evacuation to Ottawa. Once in hospital, his deadly spiral stabilized.

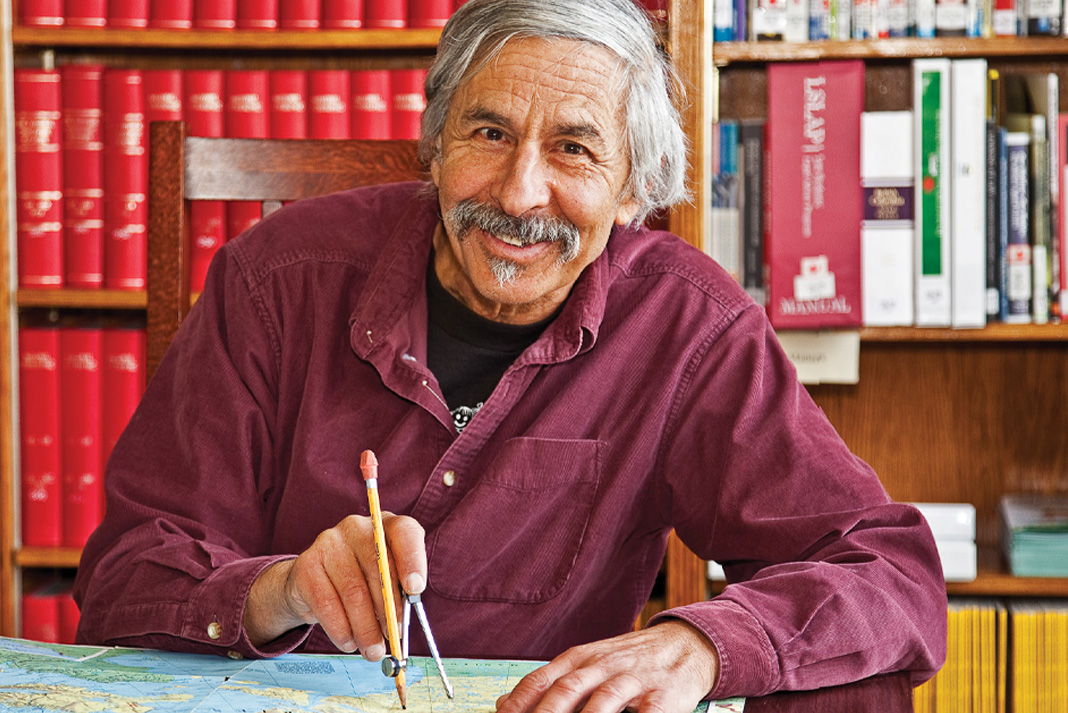

The journey brought wider renown to a lifetime of exploration, yet prior to Ellesmere, Turk, 69, was relatively unknown. His obscure, analog adventures unfold over months and years, well beyond today’s digital attention spans. He doesn’t use GoPro or Twitter; his no-frills website is efficient but basic. Red Bull isn’t knocking at his door to back his projects, but Turk has never confused outdoor adventure for a marketing stunt.

The real distinguishing factor for Turk, the core of his wonderful anachronism, is that small-craft exploration is not an end in itself, but a means to develop and test explanations for unanswered questions in human history. How do Arctic peoples relate to their Asian forebears? How did the earliest migrations to North America happen, what beliefs motivated them and what tools or vessels helped them traverse incredible distances?

“It’s boring to just recite details from the trip,” says Turk. “I’m more interested in what grand journeys like Ellesmere, and the massive migrations undertaken by our ancestors, can teach us. What wisdom do they impart, and why have humans undertaken such journeys throughout history?”

Against the current tide of photogenic free climbers, big wave surfers and kayakers dropping 200-foot waterfalls, Turk echoes an older tradition of scholar-explorers who sought answers in the wild, beyond the reach of laboratories and scientific debate.

Raised in rural Connecticut, Turk earned a PhD in organic chemistry in 1971 from the University of Colorado. The same year, he co-authored the first environmental science textbook in the U.S., triggering a movement that led to the adoption of environmental studies curricula across North American schools. After a decade immersed in academia, mounting frustration with the conventions of career and consumer society prompted Turk’s decision to leave the laboratory for a life of adventure.

Turk’s maritime exploration began in 1979 with a solo paddling effort around Cape Horn in Patagonia. A harsh initiation that ended prematurely when waves pinned him against coastal cliffs—shattering his kayak and separating his shoulder—Turk followed this with an unsuccessful attempt at the Northwest Passage.

Recounted in Cold Oceans (1998), a series of arresting vignettes from his early adventures—many ending in desperation and failure—Turk’s 1988 expedition from Ellesmere’s Grise Fiord to Greenland was his first major success. The episodes collected in the pages of Cold Oceans are about pushing limits and trespassing into danger, each a sum of risks taken and consequences reaped, a portrait of determination from someone in so deep he has everything to lose.

In a two-part journey beginning in 1999 and finishing in late 2000, Turk kayaked 3,000 miles from the northern tip of Hokkaido, Japan, along Siberia’s Kuril Islands and Kamchatka Peninsula to the 65th parallel, finally crossing to Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait. It was his first major scientific expedition, aimed at testing the possibility of early human migration from modern day Japan to the Aleutian Islands.

In the Wake of the Jomon (2005), explores this thesis of ancient maritime migration as an alternative to the land bridge theory, the long accepted account of a gradual, ambulatory crossing of the Bering Strait when sea levels were much lower. Could a small band of early mariners have paddled dugout canoes over the horizon in an inspired pursuit of errant whale pods or a cosmic imperative, like Moses and the Red Sea? Turk retraced their likely itinerary, meeting indigenous Koryak communities along the way, descendants of the Jomon.

“If I could understand why the Jomon migrated across the Arctic,” muses Turk, “I might also understand why the first Stone Age adventurer hollowed out a log and charged into the surf, the notion being that a love of adventure helped transform bipedal primates into human beings.”

Appreciating Turk’s marriage of science and adventure requires a look back at the figures who emerged after exploration’s Heroic Age in the early twentieth century.

With the exhaustion of terra incognita and historical firsts, a new breed of explorer appeared, pioneered by Knud Rasmussen’s five-year dogsled across Greenland, Arctic Canada and Alaska into Siberia. Rasmussen suspected, and in time demonstrated, that the scattered pockets of Inuit peoples across the sub-polar region were ethnographically one, despite their mutual isolation. The English publication of Across Arctic America (1927) unearthed a rich new vein for exploration, potentially limitless because it was not defined by geography or historical firsts.

In the tropics, Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki (1948) and Colin Turnbull’s The Forest People (1961) ignited popular imagination using expedition-based research on similarly remote, pre-modern populations in Polynesia and Central Africa. Like Rasmussen, both defied sensible thinking to remap our understanding of human place, early migration and the unique, near-forgotten worldviews involved. That their theories were later dismissed did not diminish their stature as visionaries or impugn their expeditionary approach to science.

As controversial as these adventurers were in their day, Turk’s written work has met similar criticism.

“Anthropologists got worked up, mostly because I’m not from their field, so my claims and research were dismissed as spurious,” Turk recalls. “I was misquoted and maligned in journal reviews. But that was eight years ago when there was very little evidence to support a marine migration theory.” Since then, numerous scientific papers have pursued the same thesis.

His proposal that migration was sometimes conducted out of a “spirit of adventure,” rather than out of pragmatic interests, also rocked a few boats. “In retrospect, I think it’s one of those arguments that you can get worked up about,” Turk admits, “but when you look at it closely, definitions break down. I believe we are a romantic species, even when we are being pragmatic; even if that sounds contradictory.”

Decades of maritime and terrestrial exploration—kayaking, skiing, trekking and dogsledding—in the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, Greenland and Siberia saw Turk’s life become intertwined with rare individuals met along the way, from Canadian Inuit to Russian Koryak. Two years after the Jomon expedition, Turk returned to Kamchatka to pursue questions that would lead to The Raven’s Gift (2010).

The book recounts his relationship with an elderly Koryak shaman whose rituals mend a broken pelvis Turk sustained in an avalanche years before. The customary quarantine between observer and narrative subject is ignored, as Turk allows happenstance, unlikely Samaritans and bitter setbacks to enrich his immersion in the shamanism of the empty tundra. The result is a stark departure from the classic exploration account, with its emphasis on victory or defeat.

“We all fail in life,” he explains. “You aim big, you fail bigger. Every failure teaches us something. In wilderness adventure, if you don’t know when to back down from danger, you’ll die. So you always need to be ready to back away—and that isn’t failure. Success is ultimately what you learn from a mission and what you enjoyed while doing it.”

With The Raven’s Gift, Turk once again polarized readers. “Some people get hung up on whether the magic and healing I undergo are believable,” he confesses. “Things do happen in this world, within and beyond human consciousness, which defy scientific logic.”

“I guess my message, or the main thing I’ve learned from living with traditional peoples, is to approach the world in a softer way: to live with less, in order for human existence to be sustainable on the planet. They take only what they need. We take and use way more than we need; the consequences are obvious.”

An increasingly rare breed of scientist, adventurer and writer rolled into one, Turk’s literary achievements are among the gems of expedition literature. Couching theories of magic medicine and early marine migration within grand kayak adventures, they become gripping narratives.

Informed by the Ellesmere odyssey, Turk is at work on a new book. It promises more of his inimitable blending of adventure and inquiry. Rather than inflaming scientists and anthropologists, “this time I’m trying to write something that connects with a wider audience—urban, rural, regardless of politics,” he says.

The new book will explore “how people reclaim control over immediate threats and risks, whether they’re hunter-gatherers in the Amazon, or citizens of the South Bronx,” he says. Turk will be spending time in both places to complete his research.

“Our individual impact on the way the world is evolving may be infinitesimally small, but we are still responsible for how we react to this evolution,” he continues. “I want readers to see what people share in these two jungles, to see that sanity at the personal level is still within our control.”

The book recounts the early Polynesian islanders who felled towering tropical hardwoods with stone tools, fashioned them into 60-foot double-hulled catamarans, and sailed 2,000 miles across the ocean to find the impossibly slim sliver of Hawaii. Returning to Polynesia, they initiated a trade route between the two outposts.

“If we look directly at this ancestral past, certain strengths emerge that we share,” Turk says. But he acknowledges that we’ve stepped away from this mode of knowledge—“The self-reliance to learn from direct encounters with nature and with others.”

So how are the feats and beliefs of our ancestors relevant to modern society? What wisdom does Turk distill from his intrepid kayak journeys and explorations into historical origins and spiritual understanding?

“Let your relationship with the world and your environment be your primary teacher.”

Listening To Spirits

A low, flat-topped, improbably purple island rises out of the middle of the river. You would have to be blind, deaf and insensitive not to know that this is a place of power in the landscape. As a First Nations elder from the Crow Nation once said: “If people stay somewhere long enough— even white people—the spirits will begin to speak to them. It’s the power of the spirits coming from the land.”

We drift lazily to the downstream side of the island to find a large eddy and join together, our little flotilla of Innova inflatable kayaks bumping softly into one another. The mystery is here, as I knew it would be, tactile and palpable before us— an eroded cutbank full of caribou bones amid the fireweed. I look at the familiar faces in our little tribe: my wife, Nina; younger daughter, Noey; her boyfriend, Glenn; and my older daughter’s husband, Deryl.

We scamper up the 10-foot-high bank, walk across the small plateau, and find a collection of long-abandoned circular homes made with closely interwoven caribou antlers—the remnants of families not so different from my own. Families who had once hunted the giant herds that migrated across the river at this wide, shallow ford.

I have kayaked in the Arctic all my life, charging hard and hungry over tumultuous seas and dangerous, shifting icepack. At the end of my Ellesmere circumnavigation—on the medevac aircraft, racing time against death—I told myself, “I’m done. Finished. Sixty-five years old; too old for this harsh environment. I quit.”

Later, lying in the hospital bed, I recalled sites I had visited during my travels: ancient stone igloos, food caches and bleached kayak ribs lying, half buried, on the beach. I thought about our ancestors who had raised families on this barren tundra and hunted these frozen seas, stealthily moving across the ice with only a rock tied on the end of a long stick, pursuing two-ton, saber-toothed walrus and Nanook, the fearsome polar bear.

I am proud of my expeditions. But there has been a sterility to these endeavors—two men alone in the vastness, racing toward a self-defined goal. So, in my late sixties, I’ve decided to turn a page and approach the Arctic from a different perspective. Now, I am back in the land that I love, but this time moving more slowly, with the people whom I love—my family.

You don’t have to GO BIG to have a meaningful experience in the Arctic. After basking in the sunshine and the flowers, we float onward, toward the ocean. There are rapids to run downstream, fish to catch, mushrooms and berries to pick and grizzly bears to startle us. This is a gift and a legacy I can continue to enjoy and can leave for my people—“The power of the spirits coming from the land.”

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.