The notorious waters of Hecate Strait separate the islands of Haida Gwaii from British Columbia’s northern coastline. Renowned for strong winds, powerful tidal currents, frequent storms and shallow waters, Hecate is listed by Environment Canada as the most dangerous body of water on the entire Canadian coast and the fourth most dangerous in the world.

John Vaillant, author of The Golden Spruce, describes Hecate this way: “The Strait is a malevolent weather factory. During winter storms, waves can reach 10 to 20 meters and expose the sea floor. The result is one of the most diabolically hostile environments that wind, sea and land are capable of conjuring.”

Crossing Canada’s most dangerous waterway by SUP

Generations ago, the Haida First Nation crossed the Strait routinely in great cedar canoes, up to 60 feet long and six feet wide. Carrying as many as 100 men, they were able to disappear back across Hecate’s moody waters where none dared follow.

The recent history of human-powered Hecate-crossings is scanter. Masset kayaker Chris Williamson made two attempts in the 1990s. One was successful; the other turned back at night by changing winds. Legendary painter Stewart Marshall from Sointula Island sailed a homemade kayak 200 nautical miles across southern Hecate in a storm, surviving for three days on popcorn and coffee before arriving at Cape St. James. In 2008, a group of four young Haida Gwaii men crossed in double sea kayaks as part of a fundraiser.

To put the challenge in perspective, in the 70 years since Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay first climbed Everest, another 12,000 climbers have stood on the summit. In the same span, you could count on your fingers the number who have paddled across Hecate.

A first, unrealized attempt

I first met Norm Hann at a storytelling festival in 2016. Quiet and confident, Norm was a successful SUP racer, well-known for long coastal journeys in support of First Nations issues. I’d recently paddleboarded from Port Hardy to Tofino, and we had lots in common. When Norm called a few months later and asked if I’d consider trying to paddle across Hecate with him, my reply was an enthusiastic yes.

The next June, we met in Prince George, with plans of carrying on toward Haida Gwaii, and tackling Hecate. But with one storm after another crashing into the B.C. coast—and no end to the foul weather in sight—we reluctantly turned around.

Thank goodness because we weren’t ready. Not even close.

A few months later, I herniated a disc in my back. Unable to even walk for months, I was devastated. The dream of crossing Hecate seemed impossible. Little did I know, the five-year recovery journey would be a gift that left us a much stronger team, and much better prepared to tackle Hecate.

A key to crossing Hecate is choosing the right weather window. No one conquers the Strait. Rather, they sneak across in a rare moment of calm, always aware conditions could change in a heartbeat.

For summer after summer, we watched Hecate’s weather patterns, recording forecast wind and wave heights versus actual buoy observations. We learned what conditions preceded rare calm periods and how long the smooth waters lasted. Entire seasons would pass without a single favorable paddling day.

As my body healed, Norm and I tackled increasingly challenging SUP expeditions together, first retracing a Gitgat Grease Trail in the Great Bear Rainforest, then rounding Cape Scott, Brooks Peninsula, and finally Cape Caution. We grew comfortable paddling side by side in rough waters, aware of what the other was thinking without words, and able to make decisions even while battered by wind and waves.

As the seasons passed, we trimmed our gear to the barest minimum and learned to load our boards so they could ride downwind swells, push through chop and land safely in surf. We experimented with a vast constellation of different boards before eventually designing our own expedition paddleboards: Norm with Sunova and me with Starboard.

At last, setting out across the Strait

In May 2023—six years after first planning to cross Hecate—Norm and I arrived in Prince Rupert by ferry, long after midnight. With rain pelting down, we pitched our tent in a dark corner of a parking lot, listening to the marine weather forecast on a crackling VHF radio. The frontal system lashing the North Pacific would dissipate over the next day, and just as we had hoped, a brief period of light and variable winds would follow. Game on.

Twenty-four hours later, we stood on the desolate shores of Rose Spit. Few words were shared as we loaded boards and double-checked GPS waypoints. Then we were off. With a brisk west wind at our backs, we knew there would be no turning back.

Gusty winds pressed us over smooth waters, and we covered 7.5 kilometers in the first hour—great progress for fully loaded boards. Then Hecate began to show her capricious nature. Ocean swell built from the north, hitting us on our rear quarter. Then the ebb tide turned to flood, and an aggressive wind chop arrived, mixing with the swell and turning the ocean into a confused mess. Our progress slowed to five kilometers per hour. Then four. Then, a painful three and a half.

The minutes and hours crawled past. We spent a lot of time alone with our thoughts. I struggled not to concentrate on our speed—for it felt dishearteningly slow. Snacks and gulps of water were stolen between strokes. On those lonely waters, we saw nothing save a few gulls. Not a single whale or boat. For 12 hours, we never stopped paddling.

Eventually, the peaks of Stephens Island appeared through mists, inching closer. Twenty kilometers to go. Then 10. Dusk had descended by the time we reached the first rocky headlands. When we crawled ashore at last, neither of us could walk very well—or form complete sentences. But we shared the overwhelming joy of having finally achieved a long-sought-after goal. After setting up a tent, we used our last reserves to cook a freeze-dried meal, then collapsed into sleeping bags.

Norm Hann navigates the offshore islands and narrow waterways of B.C.’s north coast, en route to Kitkatla at the end of the expedition. | Feature photo: Bruce Kirkby

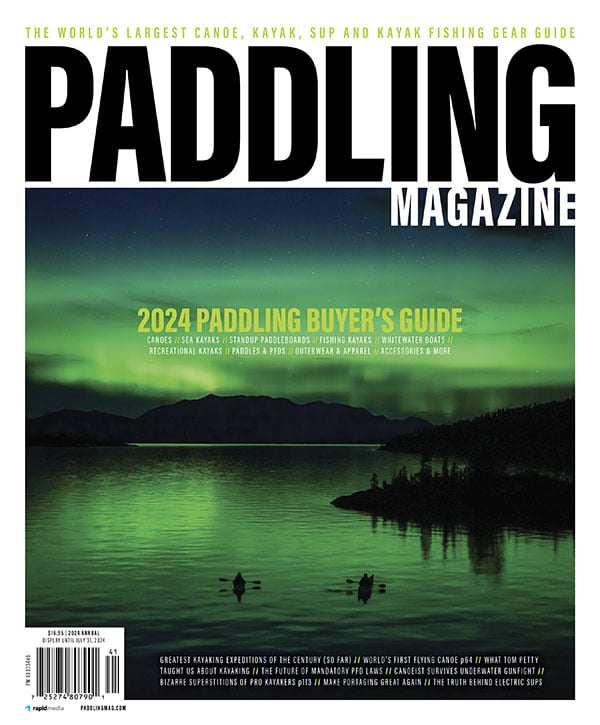

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.