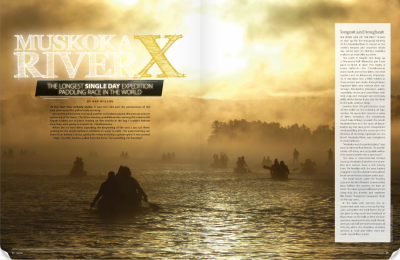

At the start line, nobody spoke. It was too cold and the anxiousness of the race permeated the pall of early morning. Misted breath hovered over each paddler as I looked around. We were an eclectic gathering of 50 teams. The three standup paddleboarders among the canoes and kayaks looked out of place, rearing up like wraiths in the fog. I couldn’t fathom how they were going to stand it for 130 kilometers. When the air horn blew, signalling the beginning of the race, I just sat there, waiting for the initial explosion of blades in water to calm. The early morning sun burst from behind a cloud, giving the misty morning a golden glow. It was surreal.

“Hap!” my wife, Andrea, called from the bow. “Get paddling, I’m freezing!”

Longest and Toughest

We were one of the first teams to sign up for the inaugural running of the Muskoka River X, touted as the world’s longest and toughest single day canoe race. Its 24-hour deadline makes it an event like no other.

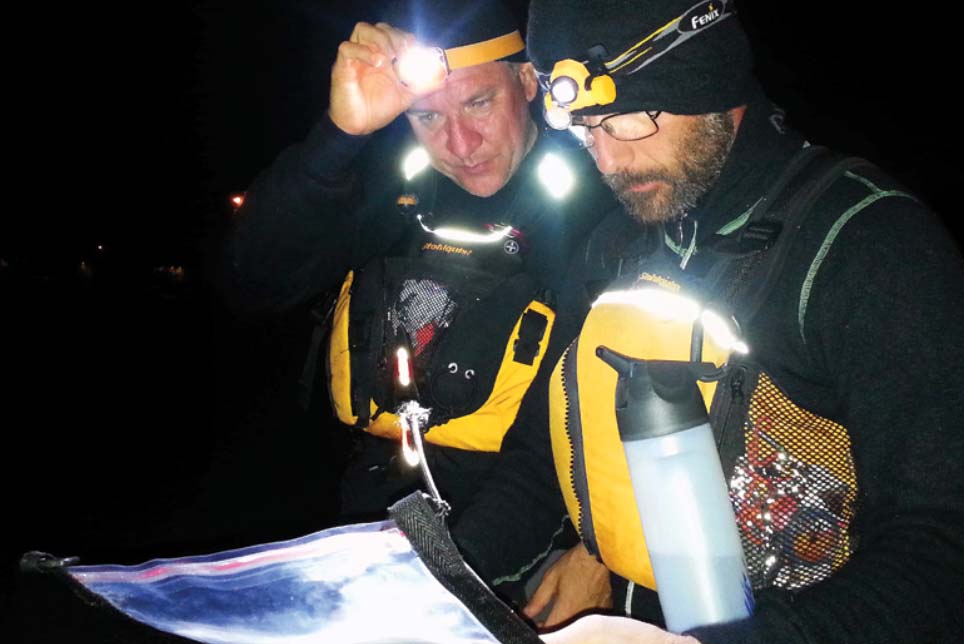

The math is simple: Just keep up a five-and-a-half kilometer per hour pace to finish in time. The reality is more difficult—the 130-kilometer route tracks across four lakes, two river systems and six kilometers of portages. It translates into 23,466 strokes at three meters per stroke, through large, exposed lakes and remote river waterways. Navigating portages, rapids, waterfalls, chutes and gravel bars with only map and compass are necessary skills; all the better if you can do them in the dark, without sleep.

Navigating portages, rapids, waterfalls, chutes and gravel bars with only maps and compasses are necessary skills; all the better if you can do them in the dark, without sleep.

Leaving from the picturesque town of Huntsville on the morning of September 14, racers first crossed a series of lakes, including the notoriously rough Lake of Bays, to reach the South Muskoka River and the town of Brace-bridge. By that time, most competitors were paddling into the sunset and the final leg of the loop, upstream on the North Muskoka River, was completed in total darkness.

“Muskoka was the perfect place,” says race co-director Rob Horton. “Its combination of history and accessible wilder-ness made it perfect for a race route.”

The area is quintessential cottage country. Muskoka chairs line the shoreline and canoes have a rich history here. I’m familiar with the area, having mapped it out for a book I wrote about local canoe routes a dozen years ago.

The local routes were the hunting grounds for First Nations communities long before the coureur de bois arrived. The river systems afforded access deep into the interior, and explorers like David Thompson navigated them on his way west.

In the early 20th century, the re-source-rich area was a mecca for loggers, who plied the thick forests for gi-ant pine to ship south and hemlock to float down to the mills to feed the burgeoning tanning industry. Look closely, and you can still see some remnants of the industry along the shoreline, mooring anchors in rock and felled trees be-neath crystal blue waters.

Self Reliance

Race day excitement had begun the night before with a mandatory gear check in.

“All teams are required to carry essential wilderness tripping gear for the duration of the race,” explained Horton. That included sleeping bags, a tent, a water purifier, extra clothing for warmth and food for 24 hours or more. Looking around at the lightweight gear spread out in front of other participants, I noticed Andrea and I had considerably more—enough for three days out, in fact. Four decades of tripping in Canada’s harshest environments taught me to be prepared. We’d chosen to secure our gear in two watertight barrels—also not the norm for racing, I noticed.

The race’s mantra of self-reliance was inspired by the adventure racing world, which both Horton and co-director Mike Varieur are regular participants in. “We learned from other races,” says Varieur, who came up with the idea for the River X a year and a half ago. “I did all the logistics work and course design, while Rob [Horton] was the technology guy.”

Horton created a virtual map, so that armchair spectators could follow each team on the race’s website. Because of the remote route and potential risks, such as hypothermia, capsizing in rapids and night paddling, SPOT satellite messengers were part of the required safety equipment. Having the ability for racers to hit an SOS button for immediate rescue was reassuring to all involved—and some would use it before the day was done.

I couldn’t fathom not doing a proper J-stroke. That alone slowed us down by two kilometers an hour. It was enough to make a marathon paddler cringe.

Reflections

I was mid-route when I started reflecting on the differences between marathon paddlers and wilderness trippers. Trippers typically use a J-stroke for correcting steerage; racers use the “hut” stroke, switching sides constantly to keep the canoe aligned. They also use bent-shaft paddles, curved to eliminate the unproductive reach of the traditional blade. I couldn’t fathom not doing a proper J-stroke. That alone slowed us down by two kilometers an hour. It was enough to make a marathon paddler cringe.

Though sanctioned by the Ontario Marathon Canoe and Kayaking Race Association—necessary for insurance—few OMCKRA members participated. All crafts in the River X had to have the capacity to carry wilderness tripping supplies, so traditional racing shells were disallowed.

The end result was that the race attracted casual paddlers and trippers, many without any racing experience. Most of the racers were just your average canoe trippers with the crazy notion that paddling and portaging 130 kilometers in one day would be fun.

Pushing Upstream

Stroke after stroke can get the mind wan- dering. As the dim haze of the evening approached, I reflected on how history has a convoluted way of repeating itself, at least when it comes to canoeing. Marathon distances were the driving element governing success or failure during the frenzy of the fur- trade and exploration era.

In 1828, Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson Bay Company, pushed his heavily laden canoe upstream 630 kilometers on the Hayes River in Manitoba, from York Factory to Lake Winnipeg, in six days. Today, the same trip going downstream takes an average of three weeks.

Simpson was known for his physical stamina when traveling through the wilderness. In his day, paddling great distances in a short time meant profit for the company; paddlers were paid to push the limits of endurance. Today, marathon paddling is something entirely different; now, we gladly pay for the opportunity to test our mettle and see if we’re as tough as our forefathers.

Day’s End

By the time we reached our third and final checkpoint in Port Sydney at 2 a.m., we were just 20 kilometers from the finish line and chilled to the bone. We’d arrived after hours of slogging upstream through shallow rapids. A weak moonlight had illuminated the shore briefly, but once temperatures dropped below freezing the river fog consumed everything. Icy tendrils worked their way down our collars and through our carefully planned layer systems.

The fog thickened until the spotlights affixed to the bow of the canoe were useless and we were forced to feel our way upriver in total darkness. At the checkpoint, we were grateful to warm ourselves by a crackling campfire. Family had come out to cheer us on and while we chatted, rested and snacked, shore-side cottagers cheered other racers as they came and went.

Officials told us close to a third of the teams had quit—some had gotten turned around, some were lost and others were just dead tired and found solace by sleeping in the forest, waiting for sun-up.

With our 24-hour deadline approaching and committed to finishing, we paddled away from the checkpoint’s warmth. But back on the water, it wasn’t long before we started to drift into sleep, paddle in hands.

“It was scary,” Andrea later told me, “it was like falling asleep at the wheel.” We would paddle a few strokes then, leaning on the gunnels, fall half asleep and drift. And we continued that way for some time.

“It was scary,” Andrea later told me, “it was like falling asleep at the wheel.” We would paddle a few strokes then, leaning on the gunnels, fall half asleep and drift. And we continued that way for some time.

It was the brightening sky in the east that revitalized us. We spent the last hour of the race in a sprint, J-stroke and all. We crossed the finish line just as the sun peaked over the horizon, 14 minutes inside of the 24-hour cut-off. Exhaustion was forgotten in the excitement of success. Aside from the race coordinators, there was little fanfare. Most of the teams wait- ed for a post-race breakfast at a nearby restaurant, and we wasted no time in joining them.

Damage Report

As I dug into a plate of bacon and eggs, we got the damage report.

By morning, six emergency calls had been placed. Two were from SPOT panic buttons, one due to a shoulder injury and another because of exhaustion. Three teams also called for assistance via cell phone, due to being lost or exhausted.

“The sixth team was heading in the wrong direction and we were watching them on the live tracker and sent a team to intercept them,” said Varieur. “Only one person was taken to the hospital, and that was for pre-cautionary measures.”

Blowing away even the race organizers’ expectations, veteran marathon paddlers Bob Vincent, 71, and bow mate Dean Brown, won first place, clocking in at 14 hours and 12 minutes.

“Our plan was to never stop paddling except for the portages,” says Vincent of their strategy. Even snacking was done in shifts.

And while Andrea and I didn’t come in first, we did receive an award of our own—we won the prize for most gear carried. Trippers to the bone, our three-day supply of food, hot coffee and gear had not gone unnoticed.

Post-breakfast, paddlers shared stories of their difficulties and successes on route—tales of rugged portages, exhaustion-induced hallucinations and hidden river entrances. We talked about why we had signed up this year and why, even though many had sworn just hours prior that they’d never do it again, most of us probably will.

It was a kayaker, Allyson McDonald, who summed it up best: “If you’re not moving, then you’re dying.”

Aside from the occasional gig playing advisor to Hollywood, teaching Pierce Brosnan how to throw a knife and paddle a canoe, Hap Wilson is an author and artist. Over his four decades spent as a writer and researcher, he has published 12 books. www.hapwilson.com.

This article originally appeared in Canoeroots and Family Camping, Spring 2014. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions here, or download the Paddling Magazine app and browse the digital archives here.