When Frank Goodman died in late February 2017, peacefully at age 86, the kayaking world bade farewell to one of its pioneers and greatest talents. Many paddlers knew Frank as a presenter at sea kayaking symposiums in the 1980s and ‘90s, or at least as the legendary name behind Valley Canoe Products and iconic, enduring kayak designs like the Anas Acuta, Skerray and the Nordkapp.

Remembering Frank Goodman, Nordkapp designer & sea kayaking pioneer

Look a bit deeper and it becomes apparent that much of what we consider the defining features of the sea kayak—innovations like waterproof hatches and bulkheads—owe their origins to Frank Goodman. The expeditions that defined a golden era of sea kayak exploration, including circumnavigations of Great Britain, Cape Horn, Australia, New Zealand and Japan in the 1970s and ‘80s, were done in Frank Goodman-designed boats. Even if we are not of the older generation of paddlers who picked up some bits of knowledge from Frank himself, we are probably just one mentor removed from someone who did. It seems almost inevitable that Frank Goodman had to come along to make our sport what it is.

Look beyond the well-known lore of Frank Goodman the sea kayaker—there is so much more to the man. He was an artist, designer, builder, educator, musician and jazz enthusiast, father, polymath and creative force. It seems almost a fluke and our very good fortune that this young art teacher from the landlocked English Midlands somehow ended up devoting his prodigious talents to sea kayaking.

Frank’s formative years

Frank Goodman, the second oldest of four children, was born in 1930 in the town of Hinckley, in Leicestershire. His love of craftsmanship and adventure may have come from his parents, who Frank’s daughter, Anna Conochie, laughingly remembers as “slightly crazy in a good way.” His father Lance Goodman was a craftsman, the son in the established Goodman & Son joinery business. His mother, Marjorie, possessed the family’s adventurous streak, renowned as the first woman in Leicestershire to perform an aerial loop as a passenger in a crop dusting plane.

Frank used to say he lacked the hand-eye coordination for school sports like rugby, soccer or tennis but he loved the water and swam competitively for the county. He excelled in the arts and went on to train as a teacher in woodwork, metalwork, art and design at what is now the prestigious Loughborough University.

Besides his love of swimming, Frank’s young adult resume shows little sign of the fanatical paddler he was to become. He devoted himself to jazz, playing clarinet at a semi-professional level. He completed his year of compulsory national service in the Royal Airforce, where he played in a RAF band. He met and married Doreen, a teacher in Hinckley. Typically dreaming of the future, the first home he bought was an Edwardian detached, big enough to raise a family. He would live here the rest of his life. The newly married Goodman couple would tear around Leicestershire County in the open cockpit of a three-wheeled Morgan sports car. Frank was beginning to seize hold of a vision he’d outlined in a carefully illustrated journal as a small child, in which he was the commander in chief of a club that had its own sports car, boat and airplane.

In the mid-60s Frank was a mid-life professional and an established lecturer in woodwork, metalwork, art and design at Clifton College in Nottingham. He had two daughters, Anna and Penelope. He did not abandon youthful adventure; if anything he was barely getting started. He dabbled in climbing like many British sea kayakers in those days and was a member of the Royal Geographical Society, joining two expeditions to Yugoslavia in 1963 and ’65 to indulge his lifelong interest in geomorphology.

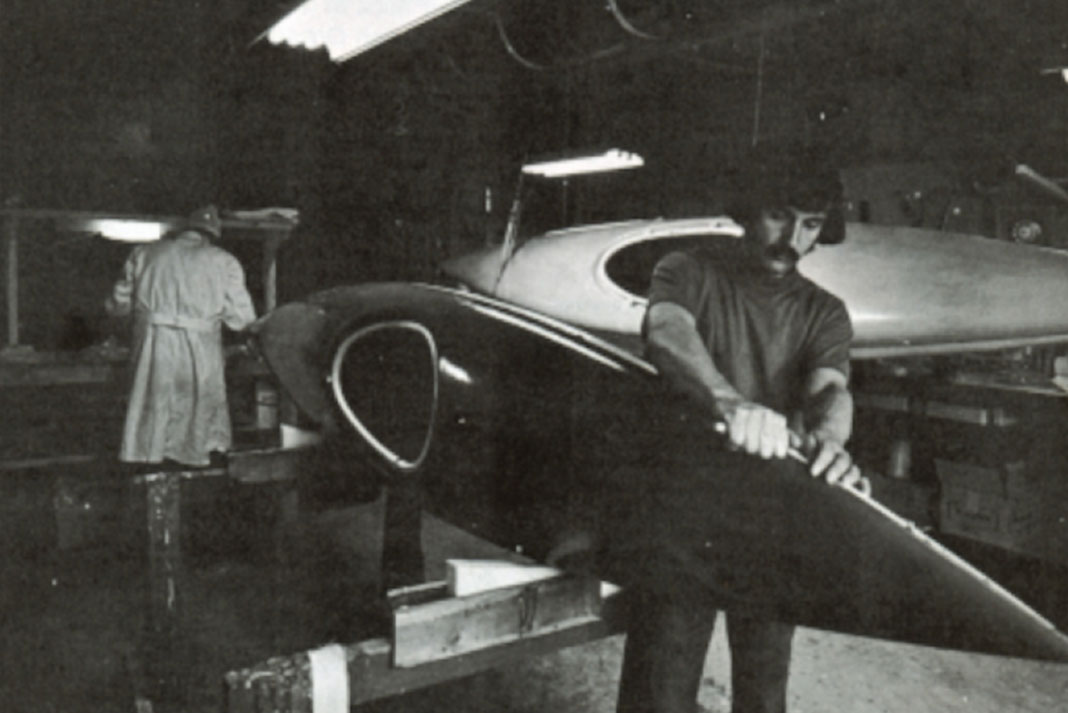

He once told a reporter that he got hooked on kayaking while “messing about” in a homemade kayak in ocean surf in 1964. By the late ’60s he became an avid whitewater slalom kayaker and began to turn his design skills to the problem of equipment, creating a fiberglass slalom kayak for his college’s physical education department and fellow paddlers in the Soar Valley Canoe Club. His design was so successful, it was ripped off by a commercial producer. Frank considered quitting teaching and going into the kayak business himself, as a way to combine his loves of paddling and design, but then received a Fulbright scholarship to lecture in California for a year.

In 1969 Frank packed his family off to San Jose and shipped along a fiberglass kayak mould. While in the U.S. he built a kayak in his garage, which he paddled down rivers in the Sierra Nevada and raced to 12th place at the legendary Arkansas River Race in Salida, Colorado.

In 1970, he returned to the U.K. where he advanced to Britain’s first division in whitewater slalom at the age of 40. Kayaking had consumed him as a hobby and now he followed through on his dream to make it a business, starting up Valley Canoe Products in Nottingham.

Designer: The making of the Nordkapp

In the beginning, Valley Canoe Products produced Frank’s Soar Valley Special slalom kayak, surf kayaks and starting in 1972, one of the very first commercial fiberglass sea kayaks, the Anas Acuta. This iconic hard-chined sea kayak, named for the northern pintail duck whose stern it resembles, is still produced today. At the time it was already a popular design in the U.K., adapted by various small-scale builders from a West Greenland hunting kayak brought from Igdlorrsuit to Scotland in 1959 by an anthropologist named Ken Taylor.

In 1974, 44-year-old Frank was still pushing himself as a paddler; he and Nigel Matthews, a Leicestershire outdoor education teacher, kayaked across the Irish Sea in Anas Acutas. Frank also tied the world record for the longest surf at more than four miles on the Severn Bore, an accomplishment about which he was characteristically modest. “If you were discussing the area it might come out in general conversation that he used to surf there,” says Nigel Dennis. The world record would be brushed off as some stroke of luck.

In 1974 came another pivotal moment for Frank. He was approached by Nigel Matthews, Sam Cook and other members of the British Nordkapp Expedition to design a kayak for their proposed 500-mile journey to Europe’s Northern Cape. Having just circumnavigated the Isle of Skye in Anas Acutas with gear strapped to the decks in plastic bags, they saw the need for a kayak up to the task of longer voyages.

Frank was a bundle of creative energy and enthusiasm, brimming with design ideas and ambitious dreams. He poured his heart into the task, working closely with the expedition members, even accompanying them on a test trip to the Farne Islands and tweaking prototypes to their feedback. The resulting Nordkapp sea kayak is said to be essentially a larger, faster, soft-chined version of the Anas Acuta, the lines of a West Greenland hunting craft still visible in its hull and adding to its enduring appeal.

“He did a terrific job with that boat,” expedition member Sam Cook recalls. That Nordkapp Expedition was to be the moon launch of modern sea kayaking, spinning off a surprising number of equipment innovations including the first Lendal sea kayak paddle, the first PFD with pockets to replace bulky life jackets and the first neoprene sprayskirt. But the crowning glory was the Nordkapp kayak itself, which premiered many signature design features of the modern sea kayak: waterproof bulkheads and hatches adapted from sailboats, a cockpit pump, deck fittings, a compass recess and an early version of the day hatch.

The kayak’s subsequent history is well documented. A Nordkapp resides in the collection of the British National Maritime Museum as “the archetypal sea kayak.” It became the go-to craft for a global hit list of circumnavigations. In New Zealand, a builder named Grahame Sisson began producing Nordkapp-inspired designs for the southern hemisphere. In its wake came other classics such as the 16-foot Selkie and Skerray XL for the North American market. In the mid-1980s, at the urging of close friend and fellow sea kayaker Stan Chladek, Frank built the round-chined Pintail ocean playboat modeled on the Anas Acuta that expanded the interest for shorter trips.

Through it all, the Nordkapp “was Frank’s baby,” Sam Cook says. He treated it like one, following its adventures with a fatherly pride. When the Nordkapp Expedition arrived at their destination in northern Norway, they saw someone signalling them from the top of the cape with a mirror. It was Frank, Doreen and their two daughters. “He was so interested in how these boats performed that he drove with his whole family up the whole length of Norway to meet us,” says Cook.

Adventurer: The Cape Horn expedition

By the mid-70s Frank’s passions had turned almost exclusively to sea kayaking. One can imagine him looking out from the North Cape in 1975, dreaming of taking his baby on a grand expedition of his own. In 1977, he did. Goodman, Jim Hargreaves, Barry Smith and Nigel Matthews paddled Nordkapps around Cape Horn along Chile’s southern-most coast.

In the expedition report Frank describes himself, perhaps with a bit of self-deprecating exaggeration, as an overweight businessman, whipping himself into shape with mile-and-a-half lunchtime runs and Sunday distance paddles on the Trent. He also resumed whitewater slalom to get fit because he found training on calm water excruciatingly boring.

A newspaper clipping preceding the expedition with a picture of Frank is captioned, “Goodman says we should be alright.” It was comically typical, says his daughter Anna, who shared a laugh with her sister when they came across the clipping recently, “because all the time when were were kids doing all sorts of hair raising things, dad would be saying ‘we’ll be alright.’ That was sort of a family saying.”

The night before the Cape Horn expedition was to depart, everyone went to bed except Frank, recalls Hargreaves. “He just disappeared down into his workshop. And when we got up in the morning he appeared with collapsible griddle that could be folded up and put inside the hatch of a kayak.

“He was always trying to improve things and he would pull all nighters all the time. Because he was fanatical about finding solutions.” Hargreaves said. “There was an idea bursting out of him every second, and he would pursue as many of them as he could.”

Frank’s pride in his own creations shines through in the expedition report, where he calls this campfire grill their most useful piece of equipment: “I made this as an afterthought a couple of hours before we left, and it saved many a meal from being deposited into the fire.”

He carried a weighty responsibility for the kayaks. “I felt that any malfunction or weakness could be laid squarely at my door,” he writes. One of the boats was found to be badly twisted from shipping and it was Frank’s job to straighten—heating it over an open fire and tensioning it in the crook of a tree overnight. After the expedition Frank asked for a critique of the Nordkapps. “They all replied that they hadn’t noticed the boats at all. I must admit that I took this to be the highest praise.” It was as if the trip to Cape Horn was driven purely by the desire to see how his beloved design would survive the ultimate sea trial.

“Dad was sort of larger than life in so many ways but he was quite a modest guy,” explains Anna. “I think partly because his standards were so high. You could never compliment my father. He was a very good soprano saxophonist but his idol was Sidney Bechet. If you said ‘that was really good’ he would say ‘it wasn’t really, it wasn’t as good as Sidney Bechet.’ The only time I ever heard him say he was really proud of himself was when he said he was proud of the Nordkapp.”

This was in later years, when she found a picture of him in a Nordkapp on the cover of an in-flight magazine. “He said, ‘I’m proud of that boat, really. I think it’s the thing I’m most proud of in my life.”

Frank Goodman was the Sidney Bechet of sea kayak design.

Teacher: The symposium years

After Cape Horn, a man named Nigel Dennis was approaching U.K. kayak manufacturers with a dream of paddling around Great Britain, despite having never sat in a kayak before.

“Frank was the only one who took me seriously,” Dennis recalls. “He always had a lot of time for people.”

In 1980, Dennis and Paul Caffyn ultimately completed the British circumnavigation in Nordkapps and just as he’d done before, Frank came out to welcome them at the end. “He went out of his way to meet us a couple of times on our trip. He was always going out of his way to support us in the sport.”

Dennis went on to start his own kayak company and instructional business. He and Frank remained close friends and collaborators in promoting the sport. In 1985 they teamed up to launch a free gathering for Nordkapp owners—the Nordkapp Meet, which later evolved into the renowned Anglesey Sea Kayak Symposium. They also established the Nordkapp Trust, a worldwide organization to “promote safe and sociable sea kayaking.”

Year after year Frank was a regular lecturer and instructor at Anglesey and other symposiums like the Atlantic Coast Sea Kayak Symposium in Maine and the Great Lakes Sea Kayak Symposium started by his close friend Stan Chladek in Michigan. Attendees remember him as gentlemanly, polite and modest, giving time to anyone who approached him. In kayaking he found a way to combine three facets of himself, says his daughter Anna—the designer, the teacher and the risk-seeking adventurer.

Frank took Nordkapps to Baffin Island with his daughter, Anna and others to paddle and share knowledge about kayak building.

“He was always at great pains to impart knowledge to other people,” recalls Anna, who remembers him fondly as an enthusiastic father who was at times a taskmaster with high expectations. He once crafted her a slalom kayak and took pains to gel-coat her name into the hull in such a way that suggested she might be spending most of her time upside down.

“I remember once as a teenager…Dad was on the bank and I was practicing and he’d always be yelling about where to put the paddle and what to do. One day another competitor came up and said, ‘Who’s the awful man who runs up and down the bank and shouts at you?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, that’s my dad.’”

Multifaceted Frank

Frank Goodman was always looking for a creative challenge. His interests ranged far beyond kayaking. Jim Hargreaves describes him as a great raconteur, a member of MENSA and a jazz fanatic with an impressive vinyl collection. Hargreaves would teasingly call it “a cacophony of disjointed, disconnected notes,” much to Frank’s scorn.

“He looked a bit like Acker Bilk—he had the same goatee beard and I think that was a nod towards the world of jazz. That was the beauty of Frank. He was a multifaceted individual. You could not possibly be bored,” says Hargreaves, who kept in touch with him for all the decades after the Cape Horn trip and delivered a eulogy at Frank’s funeral in April.

Hargreaves remembers the time Frank thought he’d come up with a revolutionary design for a sailboat, with a symmetrical hull that could be sailed in any direction. The boat sank on its maiden voyage in an icy lake with Hargreaves at the helm. “Nothing was sacred to his ingenuity, even the idea of the principle of sailing, which has been around a long time,” says Hargreaves. “As a result of his intense curiosity and stubbornness were enormous improvements and developments to existing boat design and equipment design. His characteristics were very ingenious, very creative, very determined while at the same time he always liked to use the simple approach.”

Frank designed a lot more than kayaks. As far back as the Cape Horn trip in 1977, his design credits included the Slip-on Skeg, Tie-Beam Fail Safe Footrest, Tailored Air-bag buoyancy and Chevron Buoyancy Aid. Frank would not only design equipment, he’d then design the machinery to manufacture it, recalls Hargreaves. “He designed these simple, super little white plastic toggles and basically sold them to the entire world. Every boat had them—before then they just had end loops. He probably made more money off a simple little item than he ever made spending six months designing a new kayak.”

In the mid-2000s, Frank sold Valley Canoe Products, which still turns out 40th anniversary-edition Nordkapps under the name Valley Sea Kayaks. In his seventies, Frank had to give up kayaking after back surgery, so he took up flying instead. He showed up in Anglesey with an ultralight “powrachute” aircraft and later became a master paraglider, making cross-country flights all over Europe. When he tore his rotator cuffs and couldn’t fly anymore, he returned to his love of jazz, mastering the soprano saxophone. Anna, who had worried what would happen to her adrenaline-loving dad as he aged, marvelled at this adaptability: “He really coped with getting older and he did it with his usual thoroughness, dignity and aplomb.”

In the mid-2000s, Frank sold Valley Canoe Products, which still turns out 40th anniversary-edition Nordkapps under the name Valley Sea Kayaks. In his seventies, Frank had to give up kayaking after back surgery, so he took up flying instead. He showed up in Anglesey with an ultralight “powrachute” aircraft and later became a master paraglider, making cross-country flights all over Europe. When he tore his rotator cuffs and couldn’t fly anymore, he returned to his love of jazz, mastering the soprano saxophone. Anna, who had worried what would happen to her adrenaline-loving dad as he aged, marvelled at this adaptability: “He really coped with getting older and he did it with his usual thoroughness, dignity and aplomb.”

Anna would often join Frank for sailing trips on the Mediterranean. Even then he was testing limits—always wanting to navigate the boat in tight and shallow places instead of taking the safest routes. “He did like to push; even when he was in his eighties he liked to get the maximum fun out of everything,” she says, remembering a telling quote from his Cape Horn expedition report that reads:

“There are two types of dreams that people are apt to indulge in: one is the pipe-dream, where the brain conjures up a fantasy that is so manifestly beyond the possibility of fulfilment, that no positive steps are ever taken to try and achieve realisation. The other is the dream that stimulates action because its substance is not completely beyond the bounds of possibility.”

That quote sums up Frank Goodman, his can-do mentality, his remarkable ability to take dreams from the limits of possibility and to turn them into a reality that has touched us all.

Tim Shuff is a former editor of Adventure Kayak. He bought a new Nordkapp in the mid-2000s and paddled it on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, including the Southwest Coast of Newfoundland (Adventure Kayak, Summer 2008). He then sold it for more than he paid for it, but wishes he hadn’t.

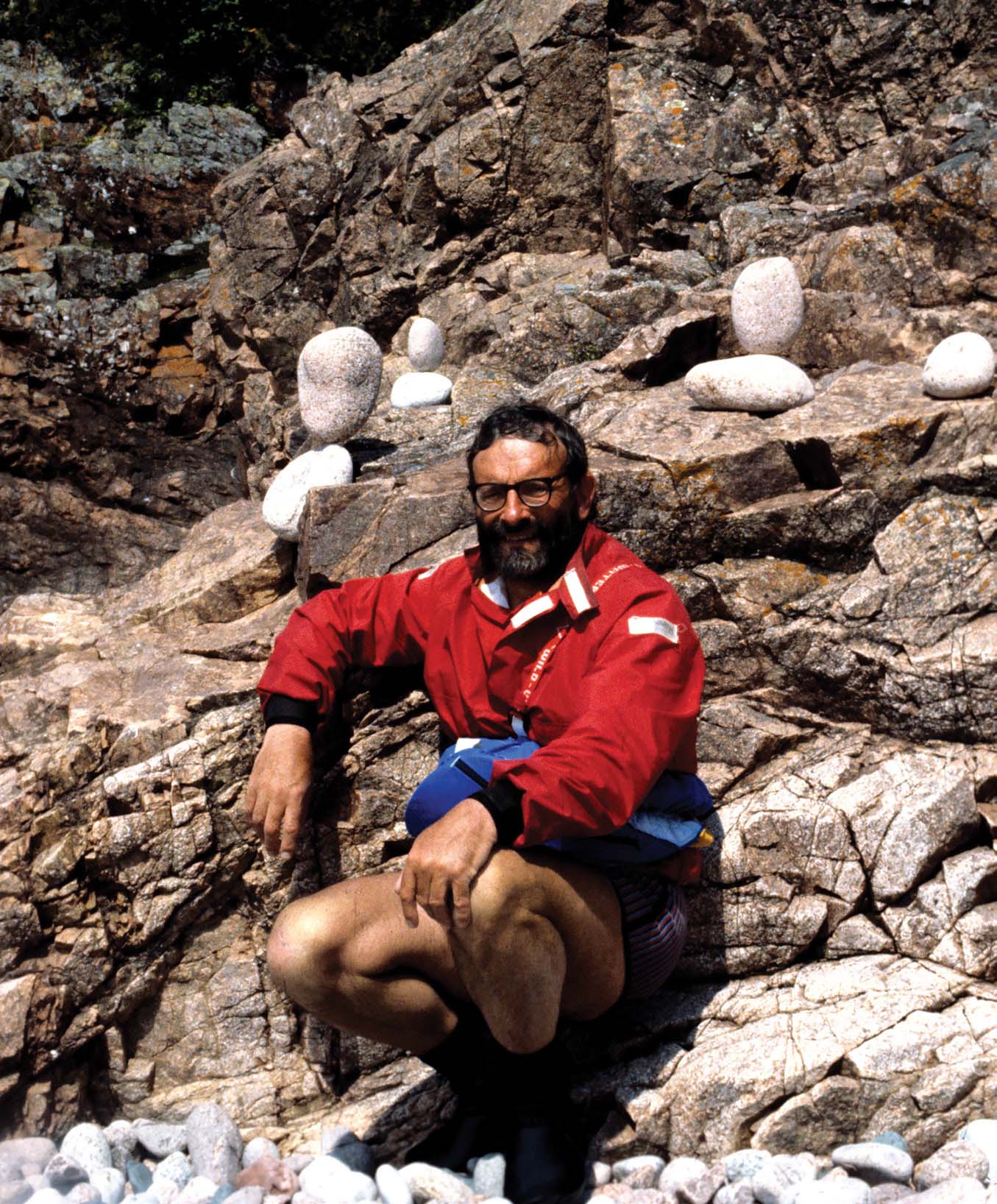

Goodman, Stan Chladek and their Nordkapps in Tallisker Bay, Isle of Skye, Scotland, summer, 1987. | Feature photo: Doreen Goodman

In the early 1970s I took up sea kayakingI on the East Coast of the USA. The sport was virtually unknown here at the time and I paddled thousands of miles without seeing another sea kayak. In the early 1980s I founded a sea kayaking tour company here in Maine and began looking for boats. I wanted something of high quality construction, with good performance, yet stable enough to use while shepherding complete beginners who might need assistance after a capsize. While attending a canoe/kayak show I ran into a dealer selling Frank’s Valley Canoe Products sea kayaks and immediately fell in love with the Nordkapp. After paddling it however I felt I needed something a bit more stable and maneuverable and so opted for Frank’s slightly more stable Weekender. At that time there were no Weekenders imported into the USA so I bit my tongue and ordered one with fingers crossed. Happily when the Weekender arrived weeks later she exhibited the same high quality and well thought out design details as the Nordkapp and while a bit more stable and maneuverable performed very well. Later that year I was a featured speaker at the Atlantic Coast Sea Kayaking Symposium and I met Frank and his wife Doreen. They were delightful people. Frank wanted to know what I thought of my Weekender and we discussed the pros and cons of the design. My main complaint had to do with with the rudder system which I felt was very susceptible to damage. Frank agreed and said he’d copied the design of rudders used in rowing shells as a stopgap solution. He promised to come up with a better design. The following year when I arrived at the Symposium Frank took me by the arm and brought me to his rental car where he opened the trunk and excitedly showed me his new, vastly improved, rudder system…clearly heads and shoulders above other existing systems at the time. That’s the kind of guy Frank was…good was never good enough and he was constantly tinkering with things in an effort to improve them. Sure enough when Frank’s next kayak design was announced (the Selkie I think it was named) it was basically like the Weekender with many of the modifications I had proposed. Whenever I think back to my years as a sea kayaker I think of Frank. He was one of the most talented people I ever met, totally committed to excellence in everything he did and, perhaps even most importantly one of the kindest, most most modest, and enthusiastic people I’ve ever known.