“A few springs ago, the idea came to me that my life would have been totally different had it not been for my association with this river.” – Hugh MacLennan, Seven Rivers of Canada

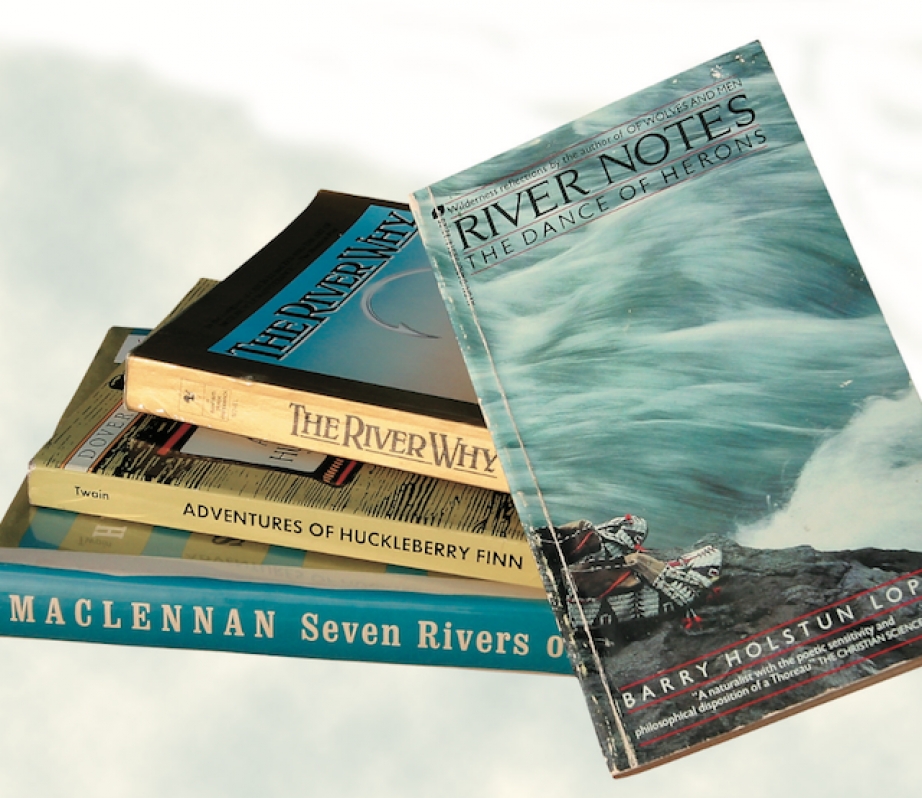

While not yet recognized as a separate scientific discipline, River Alchemy does have its fair share of ardent practitioners, and with that its own culture, words, and ideas. It has been practiced for centuries by those who use paddles, fishing rods, watercolours, or those who just like to get their feet wet. Accumulated knowledge has been passed on via apprenticeship and folk tales, only rarely making it into anything as formal as a published book. Yet some River Alchemy texts do appear—books of words that identify the greater powers manifesting themselves in moving water, and books about what it is we “get” from being around rivers.

I picked up a 1994 edition of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn before a fall river trip. Two weeks to run the Green River’s Desolation Canyon, a section that normally takes five days, leaves lots of time for hiking side canyons, eating extrava- gant one-pot meals, and reading. Each evening we would bundle-up in down and fleece, pull out the book, stare up at the stars, and read to each other by the fire.

Twain’s 1885 granddaddy of all river books has created more river quotes than any other: “…by-and-by it got sort of lonesome, and so I went and set on the bank and listened to the currents washing along, and counted the stars and drift-logs and rafts that come down, and then went to bed; there ain’t no better way to put in time when you are lonesome.”

And the favourite of raft guides: “We said there warn’t no home like on a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don’t. You feel mighty free and easy and comfortable on a raft.”

A coming-of-age novel dealing with slavery and the stultifying effects of “civi- lized” society, Huckleberry Finn has another message, one about rivers, paths, free- dom and choice. Cloaked in descriptions of the Mississippi and Huck’s log raft, the analogy is clear to those who spend time near water: growing up, traveling the stream of one’s life, learning, seeing the world for what it is, and seeking one’s own path.

Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha doesn’t sound like a good book. Judging it by the cover I managed to leave this book unread even though we “studied” it in high school. Years later, I discovered that Siddhartha is a River Alchemist’s text through and through, a story of one man’s search for happiness. The search leads to the river and a ferryman who offers to be a guide. After wandering around aimlessly for many years, Siddhartha accepts the help, but is told to look into the river to find what he is looking for: “‘It is a beautiful river,’ he said to his companion. ‘Yes’ said the ferry- man, ‘It is a very beautiful river. I love it above everything. I have often listened to it, gazed at it and I have always learned something from it. One can learn much from a river.’”

Hugh MacLennan’s Seven Rivers of Canada is now long out of print and can only be found in libraries or used book stores. Seven Rivers is based on a series of articles that appeared in Maclean’s magazine in the late 1950s and represents a time when society was just about to launch into the technology revolution. While not as heavy as Twain or Hesse, MacLennan uses rivers to identify who we are and the things we feel as Canadians. MacLennan paints our past on a screen, captures the elusive idea of Canada’s vast spaces, and anchors the streams that run through our lives. While a journalist by trade, MacLennan writes beyond the facts and hints at some greater ideas:

“I wanted to think like a river even though a river doesn’t think. Because every river on this earth, some of them against incredible obstacles, ultimately finds its way through the labyrinth to the universal sea.”

MacLennan identified in 1961 that Canadians were moving away from our rivers. Time has proven him correct, I fear.

Of all River Alchemists, Barry Lopez is the poet, and his River Notes is so profound and descriptive it drips with water in the reading. His swirling eddies draw the reader in, move them downstream, and delicately and surprisingly drop them with his famous single-sentence endings: “It is to the thought of the river’s bank that I most frequently return…and their disappearance here on the beach as the river enters the ocean. It occurs to me that at the very end the river is suddenly abandoned, that just before it’s finished the edges disappear completely, that in this moment a whole life is revealed.”

Lopez’s short stories are an exploration of the fine details of rivers and an exploration of the human soul.

There are some books that can be read over and over, and The River Why by David James Duncan is one I’ve been through a dozen times. While there are thou- sands of cheesy books attempting to address the “big question” in life, this book speaks to River People: “I couldn’t trade the trail…for a straight and narrow way—not when water’s ways, meandering and free flowing, had always been my love.” This is a story about a goofy fly fisherman who goes on a quest to fish every day of his life. He becomes a hermit, goes a little insane, gets it back together and falls in love. Proving, however, that River Alchemists find important things in unlikely places (such as fly fishing love novels), Duncan clearly writes the answer to the aforementioned big question. I’m not going to tell you what it is.