You don’t need be a class V hero to bucket list this Himalayan heaven—explore the continuous class IV canyons of Nepal’s Dolpa District.

“Where in God’s name is the river?”

“I’m pretty sure it’s just over there,” Ric spit, pointing aimlessly down the valley in response to Steve’s question. Their exchange was flavoured with a hint of the tension we were all feeling.

“Just get organized. Simon and I’ll go and find some porters,” I tried to assure the boys.

We mimed the profession to an elderly village woman, asking where we could hire someone to carry our gear. Quickly understanding us, she pointed to the hills. November is harvest season in the Dolpa region of Nepal, we learned. Any would-be porters were busy gathering food for their families for the upcoming winter, but the thought of shouldering our beastly boats, laden with camping gear and food for seven days, kept us searching.

It all started when we veered off plan the day before. Steve Arns, Simon Rutherford, Ric Moxon, Brian Fletcher and I had just arrived at Birendranagar, a small town in mid-western Nepal. From there we hoped to fly to Juphal, a remote village deep in the Himalaya with a dirt landing strip and access point to the Thule Behri River.

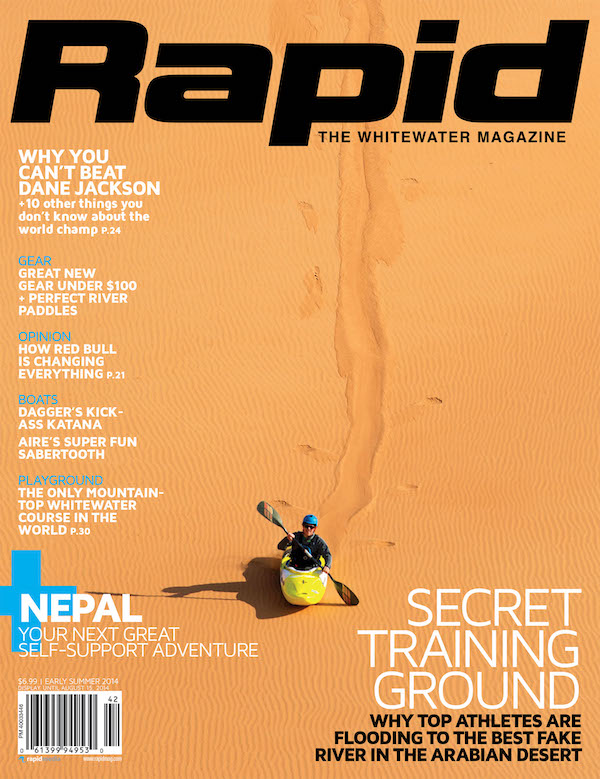

The Thule Behri | PHOTO: MAXI KNIEWASSER

“Juphal not possible,” a smiley Nepali fellow had informed us at the airport. My stomach instantly dropped. We’d traveled halfway around the world to get to the Thule.

After arguing back and forth, the man offered another option: “We can fly to Masinechaur.”

There weren’t any maps in this airport, but Masinechaur, the locals assured us, was no more than a four-hour walk from Juphal. Since it was river right, and Juphal on river left, I figured it couldn’t be more than two hours from the river. The new put-in would start us a day or two downstream of the easier section of the Thule, whitewater we’d planned to warm up on, but lacking alternatives and confident we’d find porters to help us make the trek down to the river, we stuffed our boats into a seven-seat Cessna Caravan and got ready for the flight.

A pilot’s son, I immediately noticed the plane’s non-retractable landing gear. “Makes it stronger for high-impact landings,” I explained to the boys. Before anyone could change their mind, the pilot pushed down the throttle and we took off.

Twenty minutes later we were flying through the mountains—in the Himalaya you fly through, not over, the peaks—and got our first views of the river. After 45 minutes the landing strip came in sight and I held my breath. The airstrip looked like nothing more than a short steep gravel path cut into the side of the mountain, and at over 10,000 feet planes have to land fast. In an explosion of dust, our boating gear lurched forward as the plane screeched to a halt just in front of a stone wall. “I hope the river won’t be this exciting,” Simon joked nervously.

The Thule Behri is to the ambitious weekend warrior what the Stikine is to the hardcore class V+ boater. From mid-November to late April, when the Thule’s waters flow at a moderate level, the river is continuous class IV to IV+ whitewater that cascades through the land of Dolpa, a remote western region of Nepal that was closed to foreigners until the early ‘90s.

It wasn’t until 1995 that an international team, including Charlie Munsey, Doug Ammons and Scott Lindgren, realized the Thule’s first descent, ticking off one of the last major un-run rivers in the Himalayas. Surrounded by some of the world’s largest mountains, the Thule Behri has its source in the deep blue waters of Phoksundo Lake. The lake is sacred and home to a historic monastery of the mysterious Bonpo, followers of Tibet’s ancient spiritual tradition, a religion that predates Buddhism.

The Dolpa region has steep terrain and a ruthless climate. The winter is brutally cold, the summer monsoon unleashes floods and the rest of the year a cold arid wind blows powerfully from Tibet. Life in Dolpa is not easy. There’s no doubt the cruel conditions influence the high spirituality of the region.

Polished bedrock canyons border the Thule for dozens of miles at a time and some of the world’s highest peaks drain into the valley. This river is not just hero territory. Its continuous class IV is surprisingly attainable for experienced boaters and lasts for days on end—it is no stretch to say that paddling the Thule could be the highlight in any enthusiast boater’s paddling career.

Eluded by any potential porters, we had no choice but to shoulder our boats and start moving. The path was steep, rocky and exposed, the gear heavier than we feared. However, the stunning scenery did much to alleviate the suffering on our search for the river. The Dhaulagiri Himal range—including its namesake 26,795-foot peak, Mount Dhaulagiri—towered above the river in a manner only seen in the Himalaya. “We wouldn’t have seen this if we had landed in Juphal,” I remarked. After six hours of trudging under the weight of our boats, we arrived at the river just as night fell.

We spent a cold night just upstream of a Buddhist monastery at Tibrikot. It was a fitting place to put in the Thule’s emerald water as when we awoke, we could all sense the spirituality of the place—a feeling we couldn’t quite pin down, but something special was in the air.

After just moments on the water we were into the entrance rapids of the Golden Canyon, a 10-mile-long section with walls rising thousands of feet on either side. “Man, this is spicy,” Ric puffed as he pulled into a small eddy. Starting below our planned put-in launched us into the first rapids below Tibrikot, some of the trip’s most challenging continuous flow. “Not much of a warm up, eh?” Brian said as he peeled out to continue the eddy-hopping madness. Brian seems to get more comfortable the harder the whitewater gets but if the rapids had been any steeper, we would have had to scout everything in this first section.

A couple miles downstream the water began to calm as the canyon walls grew tighter. For the rest of the day we eddy-hopped our way down playful class IV, leapfrogging one another so that everyone could get a chance to lead through the boulder maze, and hooting and hollering if anyone chose a less than graceful line. “Check out the wild patterns in these boulders,” Simon managed to yell at me over the river’s roar. A yearly monsoon carves and polishes the canyon’s boulders into colorful sculptures—paddling through these rock gardens is a highlight of the Thule.

As the warm afternoon light lit up the Golden Canyon in all its glory, we pulled over and made camp among ancient ponderosa pines. Astounded by the scenery and awestruck by the river, we concluded by a crackling fire that the Thule had some of the best whitewater we’d ever paddled.

This was my second trip on the Thule; after a run in 2008 I dreamt of coming back. As the veteran of the river, I organized a lot of the logistics, but once there I wasn’t much of a guide. The sheer quantity of whitewater was too much to remember and we treated this as our first time down the river.

The fourth day brought us to the Awalgurta Gorge, the hardest part of the river by far. Already in the entrance rapids, we were surprised by how pushy the water had become. The river had grown markedly in volume. Knowing that two miles of dangerous class V+ lay downstream we evaluated our options. “I’m out,” I said.

In 2008, my friend Danny had a terrible swim out of a sticky hole right above some horrible sieves. He had to swim back into the hole time and again to avoid getting flushed downstream and into the sieves till the team could get a rope to him. The memory was still vivid.

Waking at dawn the next morning, we cooked breakfast and packed up camp with unusual efficiency. With ever more tributaries joining, the Thule becomes big water. We were ready. After several days of continuous boating we felt strong, further aided by the lighter boats as the trip neared its end.

Just before lunch we came upon a horizon line big enough that it was at the edge of what we could safely read and run. Brian saw a line center right, boofing a ledge over a giant hole. Ric and I followed him while Simon and Steve eddied out on river left to have a better look. At the bottom, Ric and I were high fiving each other when we heard frantic whistle blasting. “GO! GO! GO! GO!” Brian yelled. We rushed to shore and ran upstream as fast as our legs and lungs allowed us. My mind was racing. Are my friends okay? What happened? What can we do?

The last beams of light in the lush lower section of the Thule. | PHOTO: MAXI KNIEWASSER

Simon, still in his boat, was getting sucked under a huge boulder. The eddy he had caught was a deadly siphon. Simon had pulled into the eddy, looking towards the middle of the river to scout the rapid. When he noticed the pull on his boat it was already too late—he was getting pulled under the boulders. In the last moment he managed to turn his boat around so he went bow first into the trap. Going in backwards would have likely been the end. As he was getting sucked into the siphon, easily big enough to swallow him and his boat, he jammed his arm in a crack in a last effort to keep himself from disappearing into the void. This stabilized him long enough for Steve to grab him and buy time for the rest of us to figure out the safest way to get him back to shore.

Himalayan rivers pose a higher than normal risk for this kind of accident. Shaped by the huge monsoon floods and the soft rock of the mountain range, the riverbeds are often comprised of massive boulders that seem delicately stacked on top of each other, especially where the river gets steeper. During paddling season when the water is much lower, the water flows through the boulder maze, rather than over it, creating many siphons—it’s the reason class IV in Nepal is so excellent, but the class V is unusually dangerous.

We always try and learn from such events, but what was there to take from this one? “I’m not gonna stop catching eddies,” Simon remarked somberly as we drifted along. He had made this move to be cautious and have a closer look at the rapid, but it had proven a near-deadly trap and a scary reminder that paddling, especially on expeditions, is a team sport.

Simon was determined to get back in his boat as quickly as possible. Less than an hour after the incident, we were traveling downstream. After another 25 miles of playful big water, class III+ and IV, we finished the Thule’s whitewater just as the sun set over the forest of Nepal’s foothills—we had paddled from the high and arid Himalaya right down into the jungle.

Sixty miles of flatwater and mellow whitewater took us toward the road bridge that would mark the end of our trip. After uncountable hours of slogging along, Steve asked, “Where in God’s name is the take-out?”