The ash canoe paddle is facing extinction. Due to the devastating effects of the emerald ash borer beetle on North America’s ash forests, paddle manufacturers may soon have to find a new favorite wood from which to manufacture paddles. The emerald ash borer (EAB) was inadvertently introduced to North America in 1990. The insect hid inside unfinished packing crates and pallets used to transport products imported from Asia.

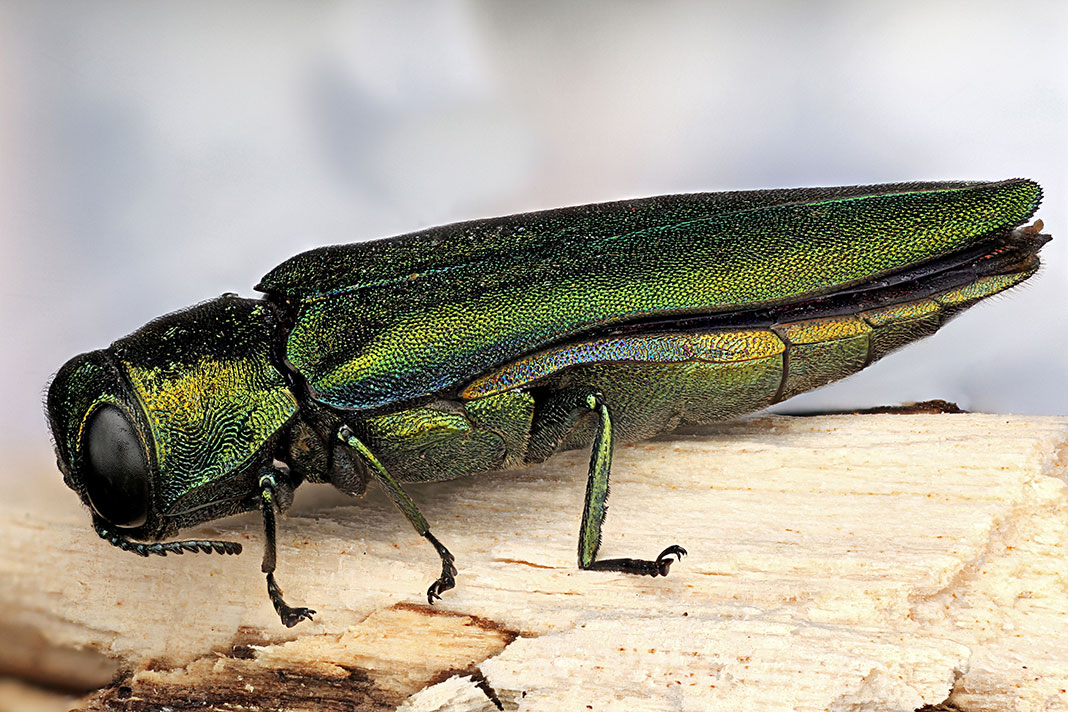

Just over a half-inch in length and strikingly iridescent, this green beetle has spread throughout the entire 65 species of ash trees on the North American continent. Capable of flight, the EAB extends its range of destruction by an average of 100 miles annually. The EAB is now found throughout the entire range of the temperate forest, from as far north as Thunder Bay, Ontario, as far west as Colorado, as far south as Texas and east to the Atlantic coast.

Why ash canoe paddles are so popular

According to Canadian and American forest agencies, of the nine billion ash trees in North America at least 500 million have perished from the EAB so far. Current estimates from these agencies suggest in spite of the work being done to save the ash trees, in as little as five or six years, commercial paddle manufacturers will be forced to find alternate sources of wood.

Ash is one of the most plentiful hardwoods and a favorite of paddlers. Generally, the ash paddle seems to be somewhere in between maple and cherry in terms of durability and beauty, yet it’s the least expensive of the three.

As well as its high strength-to-weight ratio and elasticity, ash has an extremely high impact strength and split resistance. It’s the material of choice for many canoe builders for seat frames, gunwales, thwarts, carrying yokes and decking.

What is the impact of the depleting ash used for canoe paddle

The economic impact of this destruction is estimated to be in the tens of billions of dollars. The future financial effects of lost timber production could easily exceed $100 billion. In addition to the economic impact, there will be a substantial environmental void left by the loss of the ash trees.

To infest a tree, the female EAB lays eggs in the fissures and cracks of the bark of the ash tree. Two weeks later the eggs hatch and tiny larvae chew through the bark and into the sapwood.

Larvae build feeding chambers in parts of the tree responsible for providing the leaves with the water and nutrients from its roots needed for photosynthesis production. Eventually, these larvae disrupt the flow of nutrients and water required by the leaves, which leads to the death of the tree.

An average infestation will kill a large mature tree in about three years. A heavy infestation or an infestation of a young tree can kill in as little as one year. When the life cycle of the insect is complete, the adult will eat its way back out through the bark then fly off to its next victim, mate and continue the process.

There are no widely known predators to control the EAB population in North America. Woodpeckers provide some help but offer little hope of controlling the population.

The other losses

In years past, we have seen other destructive insects and diseases plague domestic hardwoods. A hundred years ago, the great chestnut blight wiped out the American chestnut.

Eighty years ago, butternut fungus all but destroyed the butternut tree, leaving it on the endangered species list in Ontario and almost commercially unviable on the rest of the continent.

Fifty years ago, Dutch Elm Disease decimated North America’s elm population. However, there is little doubt the EAB is the most destructive and costly insect ever to invade North America.

Today, we still have an adequate supply of North American hardwoods. Aspen, birch, maple, oak, cherry and the like still populate the majority of North America, so wood products will continue to be manufactured even though the iconic ash beavertail may go the way of the dodo bird.

Only time will tell whether this invasive species can be contained. In the meantime, hang your ash beavertail on the wall. It may be a rare artifact someday.

This article was first published in Issue 57 of Paddling Magazine. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

Fear not, canoeists. Paddles are manufactured in more hardwoods than just ash. | Feature Photo: istockphoto.com/marekuliasz