In a world with endless options, how do you choose your next adventure? We trust the word-of-mouth recommendations from fellow paddlers. Our community of adventurous canoeists, kayakers, whitewater boaters and standup paddleboarders have explored countless waterways around the globe. On the following pages, we’ve delved into our 26-year history making magazines and asked 24 longtime editors, writers, photographers, contributors and collaborators to share their favorite trips, offering a glimpse into the journeys closest to their hearts. From serene lakes to roaring rapids, day trips to multi-week journeys, and backyard jaunts to international waters, these routes will inspire your next unforgettable adventure.

Bruce Kirkby

Hot spot

British Columbia

Checleset Bay Ecological Reserve, British Columbia

Duration: 1–2 weeks, 37 miles

A one-hour water taxi ride from Fair Harbour brings paddlers to the biologically rich waters of Checleset Bay Ecological Reserve. Paddle north to take it all in.

Why you should go: This off-the-beaten-path area offers the best of Canada’s wild west coast—untracked beaches, towering old growth, windswept headlands, even rafts of curious sea otters—all within a relatively sheltered environment in the lee of the towering Brooks Peninsula. I’ve traveled these magical waters more than 10 times and am still drawn back. Together with my wife and young boys, we spent 17 idyllic days paddling and beachcombing.

Bruce Kirkby has been a regular contributor to Rapid Media since he nabbed an Adventure Kayak cover shot in 2004.

Tim Shuff

Hot spot

British Columbia

West Coast Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Duration: 2 weeks, 180 miles

Winter Harbour in Quatsino Sound to Tofino in Clayoquot Sound. This route would ideally be paddled during a calm, sunny stretch of August.

Why you should go: Many years ago, I kayaked the whole west coast of Canada, from Prince Rupert to Victoria. This section was by far the highlight. This point-to-point route takes in all the greatest hits of Vancouver Island paddling—the north and south Brooks Peninsula, Kyuquot Sound, Nootka Sound and Clayoquot.

Tim Shuff joined the team as assistant editor of Canoeroots for the second-ever issue of the magazine in 2003. From 2006 to 2010, he was editor of Adventure Kayak. His Waterlines column appears in every issue of Paddling Magazine (page 27).

Brendan Kowtecky

Hot spot

British Columbia

Nuchatlitz, British Columbia

Duration: 1 week

I began this trip at the northeastern tip of Little Espinosa Inlet, but boat shuttles from the nearby town of Zeballos and a handful of operators run trips here during the summer months.

Why you should go: Nuchatlitz is special because you have paddling options in almost all conditions. On a calm day, you can explore the exposed outer islets. If you’re feeling adventurous, you can cross over to Catala Island and spend a night camping—be sure to keep an eye out for sea wolves. When the weather acts up, you can explore the protected bays of Nuchatlitz Provincial Park or even paddle east toward Brodick Creek.

Brendan Kowtecky’s first photo for a Rapid Media publication was published in the Spring 2015 issue of Adventure Kayak.

Cristin Plaice

Grey Lake, Torres Del Paine National Park, Chile

Duration: 1 day, 18 miles

Starting on the shores of Grey Lake in Torres del Paine National Park, this one-day trip takes you past spectacular views of Paine Grande and Grey Glacier. It then begins its descent down the Grey River, merges into the Serrano River and ends in the Serrano Village.

Why you should go: There’s a reason Torres del Paine National Park is considered the eighth Natural Wonder of the World and has been named a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. This world-class adventure destination is known for its famous hiking and climbing routes, but I think it’s best experienced by kayak. Think otherworldly mountains, glaciers, icebergs, canyons, wildlife and turquoise water. I don’t think there’s a place I’ve ever wanted to go back to paddle more.

Cristin Plaice joined Rapid Media in 2016. She is the publisher of Paddling Magazine.

Jeff Jackson

Canyon of Lodore, Green River, Utah

Duration: 4–5 days, 45 miles

Brilliant red sandstone walls rise over 2,600 feet from the river, shading modest technical class III whitewater. In the midst of the desert, lush green camps and intimate side streams form oases. Permit required, which is challenging to get.

Why you should go: Easy continuous flow runs through a sublime canyon. From the first day’s imposing canyon entry, past box elder shaded camps and alongside layers and layers of geologic history, it is a place like no other. Passing under the sheer face of the iconic Steamboat Rock, passengers are silenced by its awe. The approach to Split Mountain is as unlikely a sight as you can find in nature. I was fortunate to spend several seasons guiding this stretch; all told, more than 40 five-day trips. Every single current line and thread-the-needle move has significance to me, as do the numerous side hikes to amazing views. If I were to make a canyon river from scratch, this is what I would build.

Jeff Jackson’s Alchemy column (page 70) has appeared in every issue of Rapid since 2000.

Cory Leis

Raja Ampat, Indonesia

Duration: 5–14 days

Situated where the Indian and Pacific oceans collide, Raja Ampat represents one of the planet’s richest and most biodiverse marine ecosystems. Paddleboarders can center themselves around land-based accommodations, ranging from budget homestays to luxurious waterside bungalows, and day-trip to beautiful beaches, live colorful reefs teeming with sea life and mind-boggling karst formations. Or meander throughout the archipelago via a liveaboard boat. For the more adventurous, hire a local guide and use a touring iSUP for a self-supported, multi-week ocean mission.

Why you should go: Scribbled into any serious diver’s bucket list, the area hides various wonders above and below the surface. It’s a paddleboarder’s dream adventure trip, full of diving, snorkeling and hiking opportunities. Paddle to beaches void of footprints and into impossibly turquoise lagoons, hike up hillsides in search of the Bird of Paradise, dive and snorkel the many world-renowned reefs and coral gardens, and visit tiny, vibrant villages tucked along the coastlines rich in history and culture.

Cory Leis has been a regular contributor to Paddling Magazine since 2018.

Courtney Sinclair

Flåm, Norway

Duration: 3 days, 21–42 miles

Beginning in Gudvangen, start on an awe-inspiring paddle through Nærøyfjord, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, for 11 miles. Joining up with Aurlandsfjord, the route takes you another 10 miles farther to end in the village of Flåm. This route could be completed in the reverse direction, as an out-and-back trip or paired with a return on the electric ferry.

Why you should go: Paddling at a leisurely pace, soak in the views, swim in the fjords, stop in Undredal for brown goat cheese and set up camp along the way. The fjords tower over a half-mile high and feature powerful waterfalls with rivers for a cold dip. Watch for porpoises swimming nearby and farms high up on the mountains. This route is special to me as I guide many international guests here. Every time I paddle these fjords, it’s a completely different experience.

SUP instructor Courtney Sinclair has regularly contributed to Paddling Magazine since 2018.

Cliff Jacobson

Hot spot

Texas

Rio Grande River, Texas

Duration: 2–19 days, 30–170 miles

There are a number of options as to where to start and end a trip on the Rio Grande. The upper section, starting at Big Bend Ranch State Park down to Rio Grande Village, is easily done in nine days. Most parties take out there or continue downriver through Boquillas Canyon and get out at Heath Canyon Ranch. The lower canyon section from Heath Canyon Ranch down to Dryden is big water with many technical rapids and at least one portage. This part is very remote, and you’d better be a very good paddler because if you mess up, it’s a long way out. Go from Rio Grande Village to Heath Canyon Ranch for an overnight trip.

Why you should go: The Rio Grande River is not at all like the pictures you’ve seen in Western movies. The river flows through the Chisos Mountains in Big Bend National Park. Huge hills and deep canyons abound. It is essentially a mountain river with a fast flow. Camping and open fires (a firepan is required) are permitted everywhere. The upper section can be done in an uncovered solo canoe. It’s really fun—class I–II, maybe II+ in very high water—which is why I love it so.

Cliff Jacobson has contributed to Rapid Media publications since the Fall 2006 issue of Canoeroots.

Dale Sanders

Hot spot

Texas

Pecos River, Texas

Duration: 5–7 days, 60 miles

Running through southwest Texas, the Pecos is a clear river you can see to the bottom of. The surrounding landscape has a desert mountain look to it, with a lot of beautiful sandstone landmarks and not a lot of trees. We put in at Pandale River Crossing and took out at the Pecos River Access just south of US Hwy 90. For that last 10 miles before the take-out, it’s best to have a powerboat standing by to give you a tow in case of wind. Little cell coverage and shuttling vehicles needs to be planned in advance.

Why you should go: I’ve paddled a lot of rivers around the United States, and the Pecos is the best-kept secret. Everything you could want is on this trip. You’ve got some class I and II rapids, some class III, and even one class IV that most people portage. There’s one place you can hike near the river and see pictographs. You won’t see anybody else on this trip—you’re in the wilderness. It’s an ideal early spring trip because there isn’t a lot of water the rest of the year.

Dale “Greybeard” Sanders was first featured in the Early Summer 2016 issue of Canoeroots. A film about Dale’s record-breaking journey down the Mississippi River, entitled Grey Beard: The Man, The Myth, The Mississippi, won Best Canoeing Film at the 2023 Paddling Film Festival.

Joe Potoczak

Lehigh River Gorge, Pennsylvania

Duration: 1 day, 9–22 miles

Within a commuter’s throw of the largest metropolitan population in the U.S. is one of the most magnificent river gorges accessible to every level of whitewater paddler. Most run the nine-mile upper section, but the Lehigh finds true class II–III boulder garden form on the lower 13 miles beginning at Rockport.

Why you should go: Hemlock and rhododendron ravines, sandstone faces and waterfalls steal the show within the 1,000-foot gorge. To say I’ve paddled the Lehigh a thousand times is likely an understatement, and still, the view never disappoints.

Joe Potoczak is an editor at Paddling Magazine and Kayak Angler.

Nouria Newman

Verdon Canyon, France

Duration: Day trip, 20 miles

The Verdon Canyon from Pont de Carajuan to the Lac de Sainte-Croix (class IV+) is one of Europe’s most beautiful sections to paddle. The area is famous for multi-pitch climbing and paddling through massive vertical walls. The whitewater isn’t the hardest, but it should not be underestimated because there are quite a few siphons.

Why you should go: The Verdon is one of the most majestic places to paddle and probably the most scenic river in France, so it’s hard not to recommend it. That said, getting a local guide for your first time is better, so just hit Max from Raoul Rafting if you plan a trip there.

Nouria Newman has been a regular contributor since the Summer 2013 issue of Rapid.

Dave Freeman

Moose River North to Mudro Lake in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, Minnesota

Duration: 5–7 days, 45 miles

Follow Moose River North through Nina Moose Lake and Agnes Lake to Lac La Croix on the Minnesota/Ontario border. From Lac La Croix, you will paddle and portage along the border over the Bottle Portage in the footsteps of the voyageurs, across Bottle Lake and Iron Lake. Then portage around Curtain Falls. Crooked Lake is filled with islands and bays that you could easily spend a week exploring. From Crooked Lake, portage south into Papoose Lake and farther south through small lakes and streams to Fourtown Lake and Mudro Lake.

Why you should go: This classic Boundary Waters route has it all. One of the best pictograph sites in the region and some of the most beautiful campsites in the wilderness are found on the east end of Lac La Croix. Curtain Falls is one of the most dramatic waterfalls in the BWCA. These lakes offer great fishing for walleye, northern pike and smallmouth bass. Plus, the small lakes between Crooked and Wagosh provide solitude and are connected by tiny creeks lined with floating bogs dotted with carnivorous plants.

Dave Freeman has been a contributor since the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak.

John Webster

South Fork Payette, Canyon Section, Idaho

Duration: Day trip, 9 miles

With class III–IV rapids, solid boofs, clear water and even a stout class V—runnable at lower flows and easily portagable—it’s got everything to entertain. If this is beyond your skill level, go guided with a rafting outfit.

Why you should go: Aside from the fun rapids, I appreciate how this section gives a sense of what Idaho scenery can be. You’re sometimes below the road, deep in the canyon, making it almost feel like the famous Middle Fork of the Salmon. It doesn’t get much better for a section that’s a 90-minute drive from downtown Boise, Idaho. If you know where to look, you’ll see elk herds around the area—be careful, though, as they flirt with the road often. Eventually, the Canyon section fades into the Swirley Canyon and the Staircase sections downstream. If you’re feeling ambitious, you can paddle down to Banks, Idaho, the confluence of the North and South Forks of the Payette.

John Webster has been a regular contributor since the Spring 2015 issue of Rapid.

Neil Schulman

Lower Columbia River Water Trail, Washington

Duration: 6–7 days, 144 miles

Start at the Bonneville Dam and paddle past the basalt cliffs of the Columbia River Gorge, then through Portland and mazes of islands. The mileage looks intimidating, but the current is your friend. When you reach the lower river, the Columbia widens and resembles the sea it will soon join, full of pelicans and wide-open views. You’ll share the river with big ships but few people. Bask in sunsets on dispersed island camps. Best paddled in spring when the current whisks you along and headwinds haven’t come up yet.

Why you should go: The Lower Columbia is my home water. I’ve paddled the Water Trail countless times, both as continuous journeys and day or weekend trips. There’s nothing quite like following one of North America’s premier rivers all the way to saltwater. You’ll experience waterfall-laced cliffs, the Northwest’s second-largest city, and two enormous wildlife refuges and feel the beginnings of ocean swell. For history buffs, you’re also retracing the route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition back in 1803.

Neil Schulman’s first article for Rapid Media was published in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak. His Reflections column appears in every issue of Paddling Magazine (page 21).

Kaydi Pyette

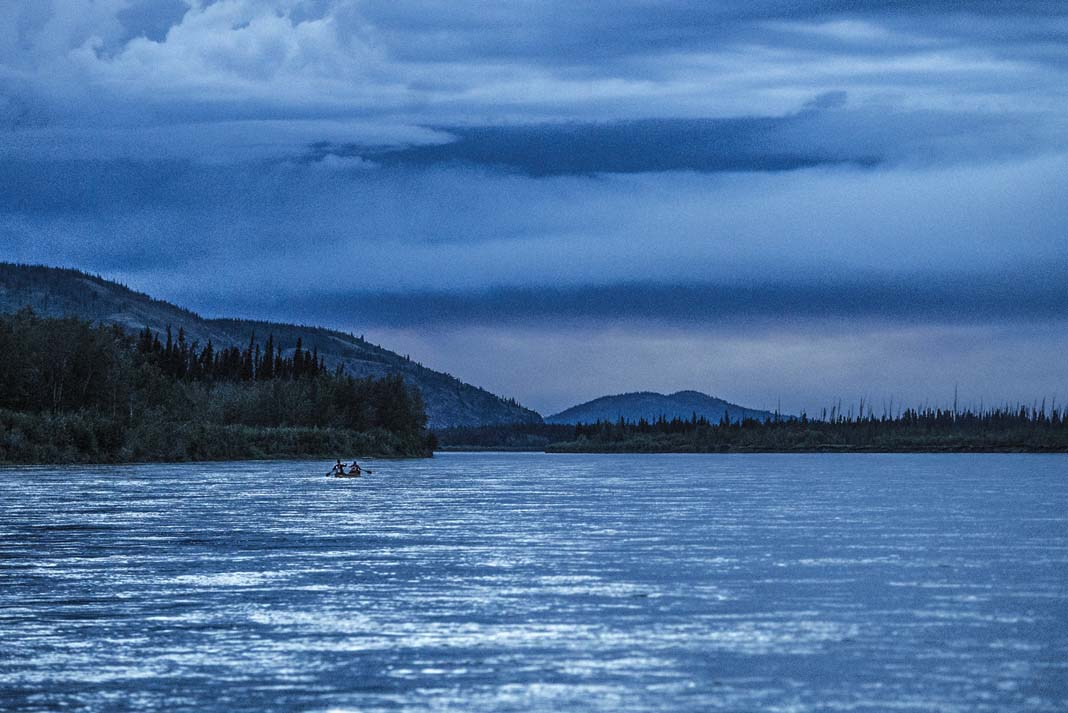

Yukon River, Yukon

Duration: Two weeks, 460 miles

The iconic, fast and (mostly) flat river journey from Whitehorse to Dawson City has a rich cultural heritage, with a strong presence of First Nations communities and the history of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Why you should go: For paddlers with solid backcountry skills, this is an otherwise beginner-friendly river route weaving beautiful and vast wilderness with the easiest logistics of any northern river trip. Camp on gravel bars, visit historic ghost towns and marvel at the midnight sun, all while watching for bears, moose and eagles. Short on vacation time? Race to Dawson City in less than 72 hours as part of the annual Yukon River Quest.

Kaydi Pyette is the editor-in-chief at Paddling Magazine and has managed Rapid Media’s publications since 2012.

Becky Mason

Hot spot

Quebec

Gatineau River, Paugan Falls, Québec

Duration: Day trip or overnight

This small reservoir above the Paugan Dam is my happy place for a quick shoulder season escape at ice-out or when the autumn colors are peaking.

Why you should go: For more than a decade, I’ve been drawn to our local watersheds. Especially the river that flows past our house—the Gatineau or, in Algonquin, Te-nagàdino-zìbi. Over many years, she has become part of me. I have paddled many of her tributaries and some of her 224-mile length. I have felt all her moods, traveled on her in every season and seen many of her charms. And this spot, only 20 minutes from our house, always revitalizes me completely.

Becky Mason’s first article for Rapid Media was published in the 2003 Buyer’s Guide issue of Canoeroots.

Dan Rubinstein

Hot spot

Quebec

Ottawa to Montreal via the Rideau, Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers and Lachine Canal

Duration: 5 days, 125 miles

Start on the Rideau River in Ottawa, below Hog’s Back Falls. Run a couple of sets of rapids and then portage to the Ottawa River at the end of the Rideau. Walk around the dam at Carillon, cross Lake of Two Mountains to get onto the St. Lawrence, and then make an industrial transect on the historic Lachine Canal into downtown Montreal.

Why you should go: This route offers a mix of urban and natural backdrops, plenty of places to resupply, and accessible transportation options to and from your put-in and take-out. I’ve done the first stretch, from my house to the eastern outskirts of Ottawa, many times, and went all the way to Montreal once as part of a much longer journey.

Dan Rubinstein has been contributing to Paddling Magazine since 2019.

Marissa Evans

Hot spot

Quebec

Dumoine River, Quebec

Duration: 5 days, 40 miles

Put in at KM 64 and spend five days paddling class I–III rapids. Finish the trip with a short paddle across the Ottawa River to the Stonecliffe public boat launch or Driftwood Provincial Park. This is a leisurely pace, allowing for plenty of time to relax at camp.

Why you should go: The Dumoine is a classic Canadian whitewater canoe trip that’s highly accessible thanks to many road access points, while feeling remote when you’re on the river. Beginners can join a guided trip, and more experienced paddlers can feel comfortable honing their skills.

Marissa Evans has been an editor at Rapid Media since 2019.

Alex Traynor

Hot spot

Ontario

Kattawagami River, Ontario

Duration: Two weeks, 125 miles

Put in 90 miles north of Cochrane at Kattawagami Lake. The Kattawagami joins the Kesagami River, then the Harricana River, and flows into James Bay.

Why you should go: The Kattawagami is an experienced paddler’s paradise in Ontario’s Arctic watershed. The river descends off the Canadian Shield, offering whitewater and picturesque campsites next to beautiful rapids and waterfalls. Farther along, the river gets bigger, and eventually, tides come into play. What makes this river so special is how varied it is. Watch a short film about the trip.

Alex Traynor joined the Rapid Media team as social media manager from 2018 to 2020.

Lorenzo Del Bianco

Hot spot

Ontario

Big Creek, Ontario

Duration: An afternoon, 5–9 miles

Put in at Rowan Mills Conservation Area and take out at Port Royal. If the wind is calm, paddle farther south into the labyrinth wetlands of Long Point.

Why you should go: A thick Carolinian canopy overhead, lush undergrowth, and the call of a northern flicker or belted kingfisher illustrate why this route has been nicknamed the Canadian Amazon. Keep an eye open for turtles, deer, blue herons, bluebirds and bald eagles. It’s an easy paddle lending itself to all levels.

Lorenzo del Bianco has been creating illustrations for Rapid Media publications since the Spring 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak.

Virginia Marshall

Hot spot

Ontario

Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario

Duration: 2–3 days, 16 miles

Easily accessible from Sault Ste. Marie, Lake Superior Provincial Park offers varied shoreline geology, ranging from fine sandy beaches to Technicolor cobbles and soaring pink granite cliffs. Start from the Michipicoten River, overnight at inviting backcountry campsites, and end at the 200-meter rock face at Old Woman Bay.

Why you should go: It’s in the name. Lake Superior. The greatest of the Great Lakes is a kayak touring destination unlike any other—a sprawling sweetwater sea containing 10 percent of the planet’s surface freshwater. Every time I slip my sea kayak into these waters, it feels like coming home.

Virginia Marshall’s first article appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak. She was the editor of Adventure Kayak from 2011 to 2017.

Mario Rigby

Hot spot

Ontario

Toronto to Ajax, Lake Ontario

Duration: 2 days, 25 miles

Start in the metropolis of Toronto and end in the neighboring town, Ajax.

Why you should go: Paddlers enjoy scenic views of the Toronto skyline and natural landscapes as they head east. This route is perfect for those who want to experience a mix of urban and natural settings and is ideal for those looking to get a taste of lake kayaking with manageable challenges. The proximity to urban centers allows kayakers to blend convenience, beauty, adventure and epic sunrises.

Mario Rigby was first featured in the 2021 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

Conor Mihell

Hot spot

Ontario

Elliot Lake–Flack Lake Loop, Ontario

Duration: 3–5 days, 25–40 miles

Just north of Elliot Lake in Northern Ontario, this canoe route is reminiscent of Algonquin Provincial Park or Temagami but without the crowds. Backcountry camping permits (Mississagi Provincial Park) are required for Flack Lake; the rest of the route is in a nonoperating provincial park or Crown land.

Why you should go: I’ve paddled this route at least eight times, with family, friends and guiding small groups. It’s truly a lost gem with easy access, convenient logistics and diverse scenery. The rugged portages are a great way to test your body and feel like you’ve earned the right to visit secluded, clear-water lakes.

Conor Mihell has been writing for Rapid Media publications since the 2005 Buyer’s Guide issue of Canoeroots.

Justine Curgenven

Round the Stacks, Anglesey, North Wales

Duration: 1 day, 7.5 miles one way

For experienced sea kayakers, start on the smooth grey cobbles at Soldiers Point, a steep beach nestled on the outside of the proboscis-like breakwater of Holyhead Harbour. After a few surfs, make a wide arc away from shore, riding the current train to the next attraction, South Stack. Lunch is at a cozy rocky beach as the tide changes, before making your way to the final tidal race at Penrhyn Mawr (“big headland” in Welsh). Surf here before finishing the paddle on the sandy crescent beach of Porthdafarch.

Why you should go: My favorite Welsh paddle takes in three iconic tidal races, an imposing lighthouse perched on a craggy island, and towering ancient cliffs pulsating with nesting birds. It’s a beautiful location and an exciting paddle that’s always different. I’ve done it dozens of times, in different ways, and it’s the paddle I most look forward to when I return to Wales every year.

Justine Curgenven has been a regular contributor since the Spring 2005 issue of Adventure Kayak.

Jessica Wynne Lockhart

Hot spot

New Zealand

Whanganui National Park, North Island, New Zealand

Duration: Day trip, 6 miles

The 145-kilometer Whanganui Journey is one of New Zealand’s 10 Great Walks—a collection of routes through some of the country’s most iconic landscapes. However, the Whanganui Journey is unusual in that it’s not a walk at all, but a canoe trip. The full 90-mile paddle takes five days, but it’s possible to experience the river’s most spectacular section on a beginner-friendly day trip.

From the riverside village of Pipiriki, catch a jet boat to the Bridge to Nowhere with local tour operator Whanganui River Adventures. After a tour of the historic site, the jet boat will drop you six miles upstream from Pipiriki, where canoes await. You’ll spend the next two hours paddling back to where you started, with towering cliffs coated in lush green vegetation and waterfalls on either side of you.

Why you should go: A site of spiritual significance to the local iwi (Māori tribes), the Whanganui River was the first river in the world to be granted legal personhood status in 2017. It’s serene, family-friendly paddling, capped with a small dose of adrenaline as you navigate the Autapu rapids, which are never larger than class II.

Jessica Wynne Lockhart has been a regular contributor to Paddling Magazine since 2015.

Brenna Kelly

Hot spot

New Zealand

Okere Falls, Kaituna River, New Zealand

Duration: 1+ hours

This river is the epitome of New Zealand whitewater in a bite-sized dose. The Kaituna River is a narrow canyon trickling with vines and greenery from top to bottom. Look for glowworms if you lose track of time playing in the last rapid until dusk. The rapids are pool-drop though pretty sporty at most flows, including a 15-foot stout waterfall. To paddle this section, be a confident class IV boater or hire a guide who will test your skills before descending the river together. The latter option is a sure way to get introduced to the community of legends while you’re there, too.

Why you should go: The two main reasons to paddle here are the warm, wild water that makes you feel like an instant pro, and the fun, vibrant community of people surrounding it. There are thousands of other river runs within a couple hours’ drive.

Brenna Kelly is the media sales lead at Paddling Magazine. She was first featured in Rapid in 2009, hucking a waterfall in the gallery section of the magazine.

This could be you in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. | Feature photo: Cory Leis

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in the 2024 issue of Paddling Business.

This article was first published in the 2024 issue of Paddling Business.