I met Terry Bachmeier, a member of the Windsor and Essex County Canoe Club, this summer as he waved to my husband Jonathan and me from a rusty breakwall elevated above the waters of the upper Detroit River. He motioned for us to land our 19- foot lakewater expedition canoe on a narrow sand beach—a public canoe and kayak launch site developed by the club.

Pointing to our story in his copy of the Windsor Star, he was enthusiastic to meet the couple “trying to canoe the entire Canadian shoreline of the Great Lakes”—a 4,000 kilometre journey from the Pigeon River on Lake Superior to Kingston on Lake Ontario.

Before launching our canoe back into the powerboat-infested waters, Bachmeier made an offer we couldn’t refuse: a paddle and pot- luck barbeque with club members 25 kilometres downstream. By this point in the trip, more than a month into the third summer of our expedition, our freeze-dried rations were reminiscent of paper-mâché paste and we welcomed all offers of real food.

Skyscrapers towered above on both sides of the river and our canoe felt insignificant compared to the multi-million dollar power cruisers that sent curling wakes crashing wide variety of species ranging from spotted Windsor and Essex County Canoe Club, into the sides of our canoe. We felt like a Smart car on a transport-ridden highway.

THE ADVANTAGES OF THE URBAN WILDERNESS TRIPPER

The busy city waterway didn’t hold the same wilderness appeal as the remote and pristine areas along the north shores of Lake Superior and Georgian Bay and I found it hard to imagine why canoe club members would enjoy paddling along such an urban and industrial shoreline. However, it didn’t take us very long to discover the advantages of the urban wilderness tripper.

Where else would you have the opportunity to canoe beside a giant 1,000-foot bulk freighter carrying 60,000 tons of cargo, barter for fresh walleye on the commercial docks, enjoy a hot pizza for lunch on the Tiki patio of a waterfront restaurant and snuggle under a down-filled duvet at a neighbouring bed and breakfast.

If you have never tried urban paddling, I suggest you do. You might be amazed at the wilderness in your own backyard.

Later that afternoon, members of the canoe club guided us on a paddling tour of the lower Detroit River. Massive Carolinian trees stood tall along the shoreline, as they had for centuries, and natural wetlands hosted a wide variety of species ranging from spotted gar pike to green herons.

Our newfound friends were passionate about the region and its environment. They pointed to a bald eagle nest high on a treetop with a young fledging tucked inside. At nearby Fighting Island, a constructed reef was allowing sturgeon to spawn in the Detroit River for the first time in 30 years—all indicators that the ecosystem is healthy.

Needless to say, I shouldn’t have worried so much about water pollution disintegrating our Kevlar canoe hull.

It’s a fact that more of us live closer to urban waterways than wilderness areas. Thanks to local canoe clubs, such as the Windsor and Essex County Canoe Club, you don’t need to leave the city to enjoy canoeing. Clubs are an excellent way to meet paddlers, learn about the natural history of the region, protect our historic right to navigate our waterways and enjoy urban canoeing adventures in your own backyard.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

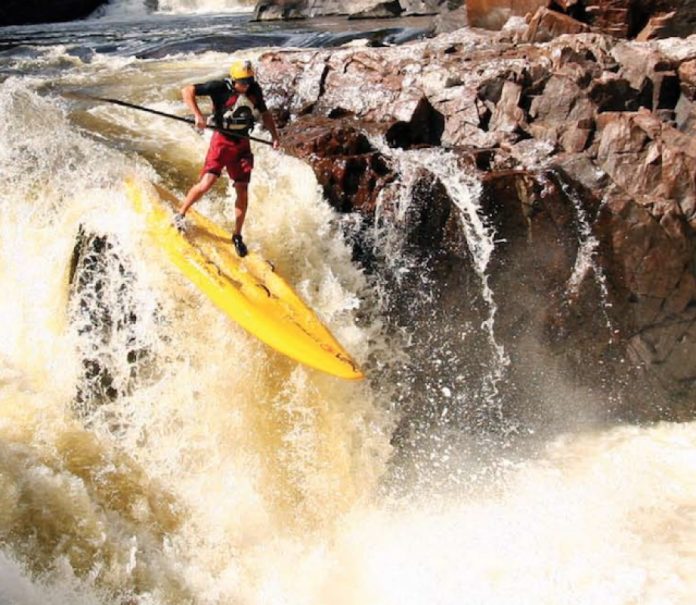

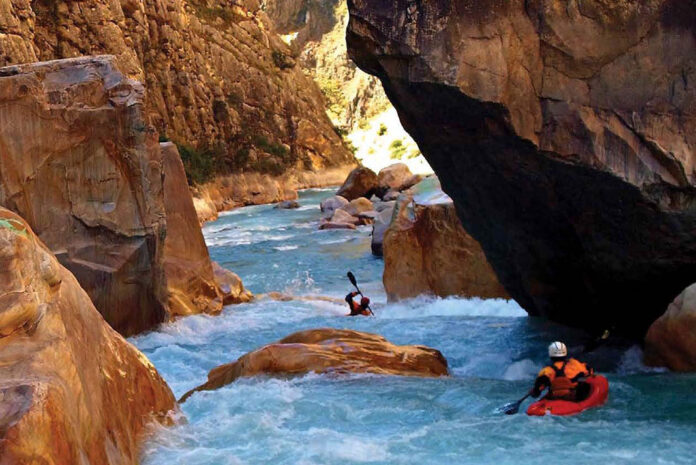

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue.

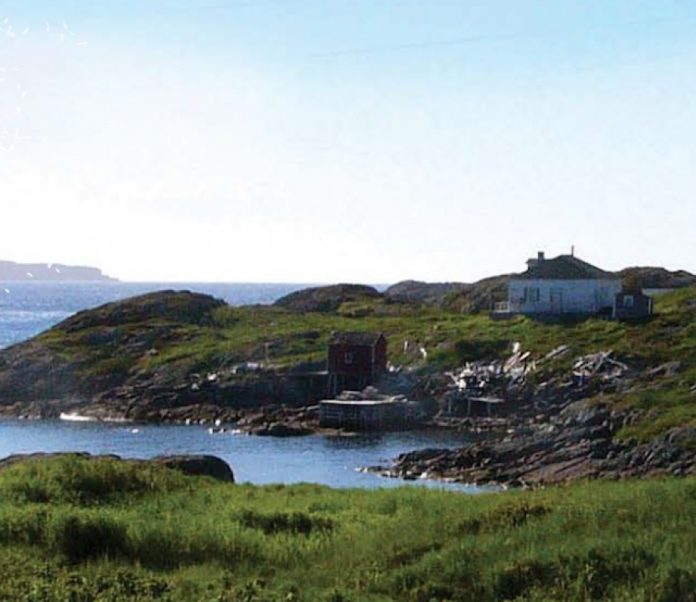

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions