Most people don’t realize how noisy their refrigerator is. Or how much of their leisure time they spend on the Internet, watching the television, or on the phone.

When we get home we don’t have those distractions so we can relax and enjoy being in the house, listening to the birds sing and the trees blowing in the wind. For years, we lived in a 12- by 12-foot wooden cabin—144 square feet, which Leon says was his true dream house! So we don’t have much room for possessions. We only have what we need which means four plates, four bowls, four knives and so on.

We do have hundreds of books because we love to read. We’ll often spend two hours a day with a good book. We love sea kayak expedi- tions because of how close we feel to nature and the way we live is an extension of that lifestyle.

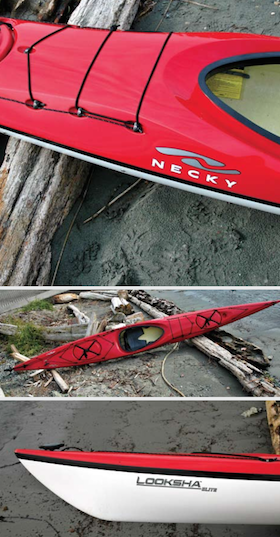

We run a kayaking store and school on Orcas Island, Washington, so in the office we have electricity, but at home, candles provide our light, a woodstove provides our warmth, we have a well for our water, and a composting toilet with a fantastic view of our pond and the forest.

Shawna is an artist so her linoleum block prints decorate the house and she’s made a beautiful glass tile mosaic around the woodstove.

We’ve built a new house so that Shawna’s 82-year-old mother and sister, who has Down Syndrome, could come live with us. We couldn’t expect them to live like we do so they have electricity in their portion of the house, called the “power pod,” while the shared portion of the house (kitchen, dining room, living room and our upstairs bedroom) is still off the grid and as simple as possible. While we built the house we lived in the upstairs of our barn where we store our kayaks. That was really cozy and also off the grid.

Through our past lives as biologists and our kayak expeditions we have come to appreciate how beautiful and fragile the planet and our lives are. It is because of this that we try to live a life that is rich in experiences, simple in what we need, and has as little impact as possible—so that we can continue to have opportunities spending time in a diverse, beautiful and untamed wilderness.

Leon Sommé and Shawna Franklin, BCU kayaking coaches and owners of Body Boat Blade international, have matched their home life to the simplicity of their paddling trips. Leon says that because of the crises that are facing our world today, like global warming, “voluntary simplicity isn’t voluntary anymore.”

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.