When paddling in crosswinds or crossing currents, it can be difficult to stay on a straight-line course from the point of departure to the destination. The direction you point your bow is not necessarily the direction you’re moving, so it’s easy to paddle a long arcing route without even realizing it.

While taking the scenic route isn’t necessarily a huge mistake, on long exposed crossings, it’s usually preferable to minimize distance. As we all remember from math class, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line.

How to paddle in a straight line in wind and current

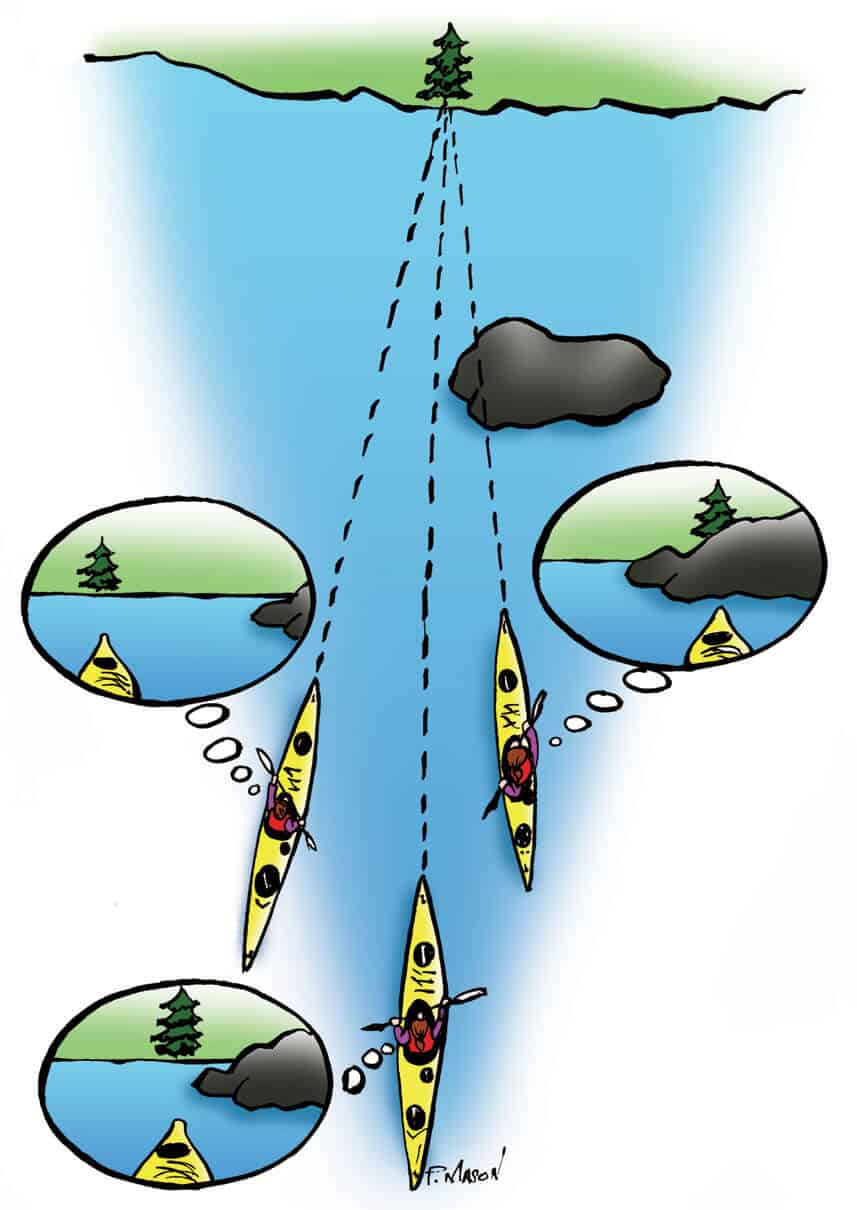

A range—also known as a transit—gives a paddler easily interpreted, “on the fly” visual feedback on course headings relative to drift. That might sound complicated, but it’s really easy. It’s a very useful tool to prevent drifting off-course due to current or wind on longer crossings—and handy for short ones, too. It is easier than reading a compass or GPS while paddling, and far less likely to make you motion sick.

To establish a range, pick two stationary reference points that are in line (the distance and roughly on your course heading). Your two points need to be some distance apart, with one closer and one farther away from your position. But they must be in line with your direction of travel. By watching how these two reference points move relative to one another, you can instantly gauge if you are drifting off course.

Say you pick a mountain peak in the far distance and a distinctively red tree on the shoreline as your reference points. If the mountain is moving left relative to the tree, then you are drifting off course to the left. If the mountain is moving right relative to the tree, then you are drifting right. If the two reference points stay aligned, then you are on course and traveling in a straight line.

By adjusting your steering and paddling to keep your range reference points aligned, you are effectively setting a ferry angle that will counteract the effects of current and wind so you can travel efficiently in a straight line on your goal. Even if the effects of current and wind change drastically during the crossing, you can adapt as needed to maintain your course.

Lake Superior’s Thunder Cape looms in the background on a 10-kilometer crossing from Pie Island. | Feature photo: Kaydi Pyette

This editorial was first published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.

This editorial was first published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.