Whether paddling your canoe tandem or solo, there is a universally necessary, yet elusive goal we all set out to accomplish: going in a straight line. The reason this seemingly simple task is so difficult is because as we paddle on one side, the strokes have a tendency to turn the canoe toward the other.

Spinning in circles is frustrating, not to mention a counterproductive way to cover water. When learning how to canoe, people often try to avoid the issue by falling back on switching the paddle from side to side in order to maintain control, but this is a tiring and inefficient method, requiring constant back and forth. Instead, the key to gaining control is learning how to do an essential canoe stroke, the J-stroke.

The J-stroke is so named because the paddle, as it moves through the water, traces the shape of the letter J. What makes the stroke invaluable to traveling straight is its combination of two parts into a fluid motion.

The first part is the forward propulsion, accomplished by your standard forward stroke. The second is corrective. During the corrective part, the paddle provides resistance to veer the bow back toward the side you’re paddling on without breaking the forward momentum gained during propulsion. It sounds simple, and, it is straightforward, however, the paddle angle and wrist movement needed to accomplish an effective J-stroke can feel awkward at first.

To get tips from an expert who spends his days making headway across breezy lakes and teaching others the ropes, we joined canoe instructor and owner of Smoothwater Outfitters Francis Boyes on the water. The details Boyes shares here will help with your J-stroke so you can take control and enjoy time spent in your canoe.

How to do the J-stroke

- Begin with a forward stroke. To take a proper forward stroke, you want to rotate your torso to reach forward toward the bow, plant the paddle blade in the water, then, again using your core for power, pull yourself to the paddle blade. This is the part of the stroke that will propel you forward.

- As the blade approaches your hip, you transition into the defining motion of the J-stroke. Turn the powerface of the paddle away from the canoe by bending your wrist so that the thumb of your upper hand points downward.

- The paddle blade pauses in the water at an angle to the canoe. The water will push on the powerface and move the stern of the canoe away from the side that you are paddling on—correcting the direction of the canoe without breaking your forward momentum. The greater the angle you use (and resistance on your blade) the stronger the corrective force.

- Slice the blade from the water to recover for your next stroke.

Common errors paddlers make on the J-stroke

According to Boyes, there are several common errors that novice paddlers make when learning the J-stroke.

- The first error is extending the forward part of the stroke too far. If you do this, then by the time you turn the paddle into its rudder position, much of the blade may be out of the water.

- The second common error is not turning the powerface of the paddle far enough. You need to bend or rotate your wrist over, so that the blade of the paddle moves into a vertical position in the water. You may need to exaggerate the bending of your wrist over further than feels necessary at first in order to reach the vertical position needed and building your muscle memory to do so.

- The third error is not ending the stroke with your paddle at enough of an angle to the canoe. “If your paddle blade ends up parallel to your canoe, it does not offer enough resistance to the water,” Boyes explains. The resistance of the water on the paddle blade is what swings the canoe so your bow heads back in the right direction following the forward stroke. You want a paddle angle that provides enough resistance to accomplish this.

More tips for an effective J-stroke

- If you are paddling tandem in a canoe, the stern paddler performs the J-stroke.

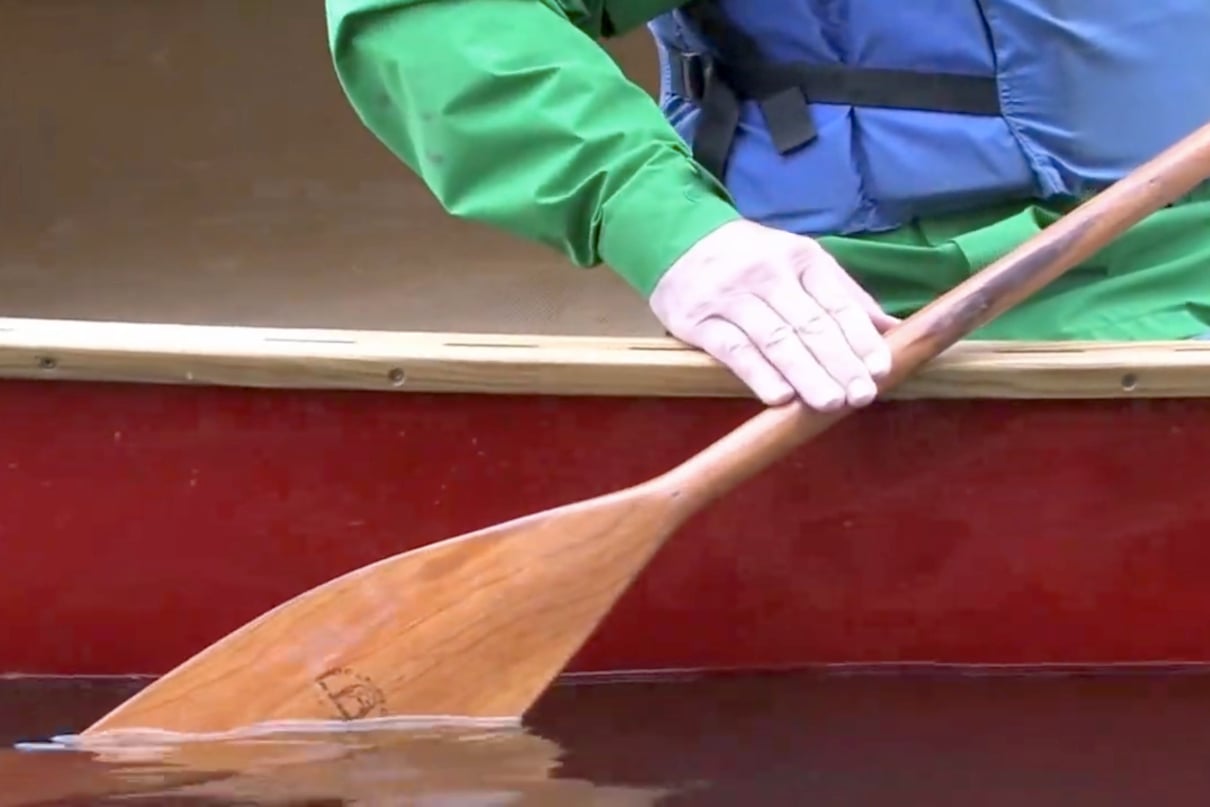

- Some canoeing purists will tell you that you should never allow the shaft of the paddle to come into contact with the gunwale of the canoe. “This is an issue of style, not function,” says Boyes. According to Boyes, allowing the shaft of the paddle to contact the gunwale, increases efficiency. When you allow the paddle shaft to contact the gunwale, the force of the water on the paddle blade is transferred directly to the canoe. Your lower arm acts as a guide only and does not tire.

- One final tip from Boyes, don’t grip the shaft of your paddle tightly with your lower hand. Hold it gently. This allows the paddle to rotate more freely as you transition into and out of the correctional phase of the J-stroke. This creates a more relaxing and fluid motion to your J-strokes.

A few more advanced strokes

The J-stroke is a foundational canoe stroke, but it is really just splashing the surface depth of canoe skills. Once you’ve gotten the hang of it, give some of these stylish and helpful strokes a try.

Goon stroke

The goon stroke is similar to the J-stroke. A key difference is that instead of turning the thumb downward to transition into the correction phase, the thumb goes upward, and the forward stroke transitions to the stern for what is known as a pry. The goon stroke is usually easier on the wrist if the J presents issues for you. It is also popular in whitewater canoeing because it can be a quick, powerful stroke, and is easier to exit the blade from turbulent currents. Why then do most prefer the J over the goon on lakes and slow-moving water? The J requires less physical energy and better maintains the canoe’s momentum.

Cross-forward stroke

With a similar goal as the J-stroke, solo canoeists often use the cross-forward stroke to keep the canoe going straight as they build momentum.

C-stroke

Getting started from a dead stop is often one of the trickiest parts, especially when solo canoeing. This is a job for the C-stroke.

Silent stroke

For a J-stroke that has both an elegant look and allows you to paddle while hardly making a sound, learn the silent stroke. The big difference between the J and the silent stroke is the recovery. The silent stroke never leaves the water, and instead, the canoeist smoothly slices the paddle blade back to the bow for their next stroke.

One of the easiest strokes you can learn, that will make the biggest difference. | Feature photo: Destination Ontario