If you ask Rob Mullen, the stink of formaldehyde can’t compare to the scent of the boreal forest in September. The Vermont wildlife artist took a deep breath 20 years ago while drawing dissection diagrams as a biology student and decided he’d rather be painting living creatures.

Mullen—who’s been canoeing since buying a Grumman with money from his childhood paper route—has used a canoe as a tool of his trade to travel the boreal forest that covers much of Northern Canada. He says you don’t need an artist’s eye to notice changes in the forest. “It’s impossible to ignore the logging, damming and mining that’s been going on.”

Mullen was on Ontario’s Missinaibi River in 2001 when he decided to assemble a team of artists to help spread appreciation for the forest to a wider public.

“There is an ignorance about this forest that is out of line with its importance. You can put the information into charts and graphs, but to motivate people you have to involve the heart, not just the mind,” says Mullen. “Plus,” he adds, “ I was tired of tripping alone and wanted some company.”

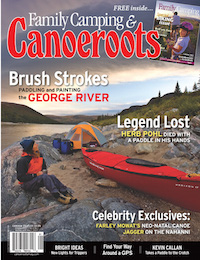

In 2005 Mullen formed the Wilderness River Expedition Art Foundation and, along with photojournalists and paddlers Gary and Joanie McGuffin, led an 18-day trip on Quebec’s George River last September with four other acclaimed wildlife and landscape painters.

Paintings from the trip will form the “Visions of the Boreal Forest” exhibition in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History next year in Washington, D.C., before touring to cities across North America.

Mullen hopes the exhibition will connect a few dots for people. “As resources around the world dwindle, the market is driving prices up and now it’s feasible to run a road deep into the forest to haul stuff out,” says Mullen. “Development has to be guided by something other than just our consumptive appetites. We’re trying to show people where their junk mail comes from.”

BY GEORGE

Though the George River sees only a few canoeing parties a year, Gary and Joanie McGuffin knew its non-technical rapids would be perfect for artists that wanted to go deep into the wilderness, not deep into the river. It flows fast and clean over a cobblestone bed along the west side of the Torngat Mountains, which separate northern Quebec from Labrador. The broad valley it has cut into its namesake plateau allows for a longer growing season than the surrounding tundra and has allowed a finger of the boreal forest to point north up the valley to Ungava Bay.

“The rapids aren’t complicated,” says Joanie, “but there are big waves and it’s fast and wide so you have to start out on the correct line. A dump could mean a lot of lost gear.”

NOT LIKE WATCHING PAINT DRY

The group took 18 days to cover 320 kilometres on the fast-moving river, which works out to about the same speed people in black turtlenecks move through an art gallery. But the pace only taught Joanie an appreciation for the artistic process. “Artists are the ultimate trippers because they take time to study the land,” she says. “Some paddlers race down a river so they can check it off their list. Artists don’t just admire the landscape from their canoe. They see a ridge and then go to see what they can see from it, or what’s behind it. It’s the best way to trip.”

WILD THINGS

Having spent 24 years seeking inspiration for her wildlife art, British-born Lindsey Foggett wasn’t about to let a little frigid whitewater stop her from paddling the George in September, a time when the 400,000-caribou-strong George River herd would be on the move.

“If you are serious about painting animals, you have to encounter them in the wild where they are behaving naturally,” says Foggett. “An animal’s manner, and even its muscle tone, is completely different in a zoo.”

STUDY IN MUD

The opaque watercolour paintings John C. Pitcher does in the field are reference studies for works he’ll start later in his Vermont studio. Pitcher did this study after noticing a wolf track in the mud beside a small creek he was fording. “A sketch like this not only gives me the proportions and colour that I need later, but also connects me to the encounter. I also take photos for later reference, but when I paint a scene I establish a cognitive connection with it and come to know it better than when I worry about what exposure will capture the blue shades of the sky reflecting off the mud.”

CRASH COURSE

Quebecker Jean-Louis Courteau was unsure about being selected to stern the fourth canoe: “Since I paint mostly landscapes the canoe has always been an ideal way for me to get around. But I paddle lakes and marshes. Whitewater was new to me. I had heard stories of gigantic waves and thunderous rapids on the George. So on the first day I was nervous. In fact, I was terrified. I didn’t want to take a bath. Now, of course, I’m hooked.”

FIELD WORK

“The George River has its guardians: the cold, the wind and the blackflies!” explains Jean-Louis Courteau.

“I have painted in Laurentian marshes and the jungles of Guatemala but I’ve never seen so many voracious little vam- pires as on the George. They made sketching and painting on the spot a challenge. And when the temperature dropped enough to keep them at bay then Tshiuetin—the north wind—took their place. But this puts you in a state of mind that lets you paint more than what the eyes see. What you experience in the field inevitably goes into the work.”

GARY MCGUFFIN: PHOTOGRAPHER AS ARTIST

“Photography is the coming together of pleasing light and lines, but it’s not just a case of technical ability, you have to show how your subject relates to its surroundings. How do you present your subject to tell a better story than the one you initially see in the viewfinder? Can you position the camera differently to show how the caribou relates to the river, or should you open the aperture and blur the background?

The photos you make on a canoe trip are different from ones you would make if you dropped into the same place on a float plane. If it takes you three weeks to get some- where, it changes how you see things when you get there.

I’m really happy when I’m in the creative zone. As the sun gets low and the light gets soft I become oblivious to everything else. That’s when I say, ‘Joanie, you’ll have to set the tent up tonight.’ And I’m gone.”