An errant hydraulic grabbed the stern of my kayak, stood me into a tail stand, and then pulled me down, down, down. The boat twisted and then: Scratch. Bang. Clunk. Stop. With the boat wedged, the current slammed me forward, smashing my face against the front deck. I pushed against the deck to stretch out straight to escape the cockpit. But the current held me with a heavy hand. Blood streamed out of my nose and swirled away in the darkness.

I was midway down the Dean River, a class IV–V river run through the remote and roadless Coast Range of British Columbia. This rapid had been no more or less difficult than a host of others. Ride the wall on river right, cross left above the snaggle-tooth rock, and drop into the quiet pool below. But as I cut left, I initiated the move with a standard paddle stroke—not a determined, urgent stroke, as if I hadn’t anticipated danger. And now I was in a death trap, jammed into an underwater cave.

I needed to push myself off the front deck. Placing both hands firmly, even with my shoulders, I pushed. Push at 100 percent, 110 percent, 200 percent. Whatever it takes.

Jon Turk’s life lessons for digging deep

I escaped the underwater cave. And the moment, horrible as it was, has become my guardian angel because I finally understood what I should have learned decades earlier. There is a huge difference between visualizing an outcome and communicating the necessary urgency directly to muscle fibers.

A dozen years later, I’m running a big rapid on the upper Indus. There is no well-planned line; I’m simply reacting to the waves and holes in front of me and struggling to stay upright. Then, hidden behind a standing wave, is the mother of all holes, yawning, mouth agape, smiling, beckoning. I flashed on my one weak paddle stroke on the Dean. Forget you are on the biggest volume river you’ve ever been on in your life, I told myself. Just reach deep inside and communicate directly with every neuron and every muscle fiber in your arms and back. Lean forward, engage your core. One simple command: Pull. Pull now. At 200 percent. Whatever it takes.

I pulled so hard I ripped open my abdominal muscles, busting a hernia. But I avoided the hole.

Back home in the U.S., I had free time as I was rehabbing from surgery and realized I needed to better understand the relationship between brain commands and muscle function.

In any sport, there are three distinct commands for muscles. The first and easiest is activation: perform the task, like a paddle stroke. Activation is simple because the nerve pathways are well established. However, muscles naturally conserve energy, so they respond with minimal effort—you can’t paddle at turbo speed all the time.

The second, more challenging command is recruitment, which refers to how much strength one needs to apply during activation. Are you coasting with a lazy stroke or going all-in?

Each muscle contains many fibers activated by neurons. A motor unit includes one neuron and all the fibers it stimulates. A casual paddle stroke on a calm river might only activate a small portion of your fibers, making it feel like you’re doing the job, but not fully engaging. To fully recruit, your brain must command all motor units and fibers to engage, requiring complete focus and commitment. On the Dean, my half-hearted stroke taught me visualizing the goal isn’t enough—concentration on recruitment is crucial.

The third and hardest command is power—transitioning muscles rapidly from partial to full strength. Think of a high jumper whose gold medal depends on one explosive leap. Or the moment a hidden monster hole appears. You need to go from 90 to 200 percent instantly. This quick power-up demands exceptional focus because the body resists unnecessary energy expenditure unless absolutely required.

Harnessing the mind-body connection

In all my younger years of paddling, I never thought about the brain’s communication with muscle fibers. I would have been a better athlete if I had. Lately, I have been finding increased performance, as well as deep joy and satisfaction from an intimate dialogue directly with the inner functioning of my body.

I wake up and greet my body, “Good morning, neurons. Good morning, muscle fibers. We have a job to do today. And I mean we, together, as a team.” I flex specific muscles quickly, slowly, halfway and all the way. “Good morning, mitochondria. Let’s process some oxygen. We’ll need that today.”

Okay. “Let’s go paddling.”

As American alpine race champion Mikaela Shiffrin once explained before a race, it is imperative to “prime your neuromuscular system.” Notice that she didn’t say “prime your muscles.” Muscles don’t do their job without the brain.

When we train for paddling or any other sport, strengthening our muscles is vital but only part of the engagement.

“Good morning, neurons. Good morning, muscle fibers. We have a job to do today. And I mean we, together, as a team. Good morning, mitochondria. Let’s process some oxygen. We’ll need that today.”

Plyometrics is a training regimen aimed at increasing rapid muscle activation—power. If you put a barbell on your shoulders and do slow steady squats, that is weight training. Jumping is a plyometric exercise that trains the same quadriceps muscles to activate rapidly. The same concept applies to paddling. Attach your paddle to a wall with resistance bands. If you use a lot of resistance and “paddle” slowly, that is weight training. Now reduce the resistance and accelerate your stroke cadence as rapidly as possible. Train your muscles to power up right now.

Once you develop strength and plyometric power, you still need to train for concentration, balance, and coordination under stress. When I attended an exercise ball class, our instructor would work us to near exhaustion for roughly 50 minutes. Then, when we were tired, sweaty, and not thinking clearly, he required us to think, balance, and be coordinated, all while powering up quickly. We’d gather in a circle, kneel on our exercise balls, and play catch with a five-pound medicine ball. The game was to throw the ball so hard that you would knock the person you were throwing to off his or her ball.

Throwing is rapid, explosive muscle activation. Catching while balancing on your knees on a ball is balance and coordination. Doing all this when you’re tired is training for real-life adventure.

You can mimic this exercise in an infinite number of ways. Run, jump, hop, or skip until you are tired and sweaty. Then kneel or stand on an exercise ball and do straight arm lifts with light dumbbells. An easier version: stand on one leg, touch your toe with your opposite hand, and reverse. Anything to train yourself to focus, balance, and perform when stressed.

Ready when it counts

At 79, I’m older now, and older people lose fast-twitch muscle activation. I spend a lot of time on my mountain bike. If I pedal uphill at 80 percent recruitment, I am slow to power up to 100 percent to pop over a sequence of rocks or a tricky hairpin corner. But I don’t want to enter the sequence too fast, so I apply the brakes lightly. Yes, crazy as it sounds, I brake while going uphill. This forces me to hit 100 percent a second or two before I need to. Then, I release the brake and engage the technical obstacle under full power.

I share this last trick as a reminder that your approach to performance will be highly personal and sport-specific. Regardless of how you do it, when you enter a big rapid or a tricky surf landing, you need to pick a line through the mayhem, of course. But you also need to dig deep, which is more than a mantra. It requires training to actively involve your entire neuromuscular system. You train so that, when it counts, you can go all in. Whatever it takes.

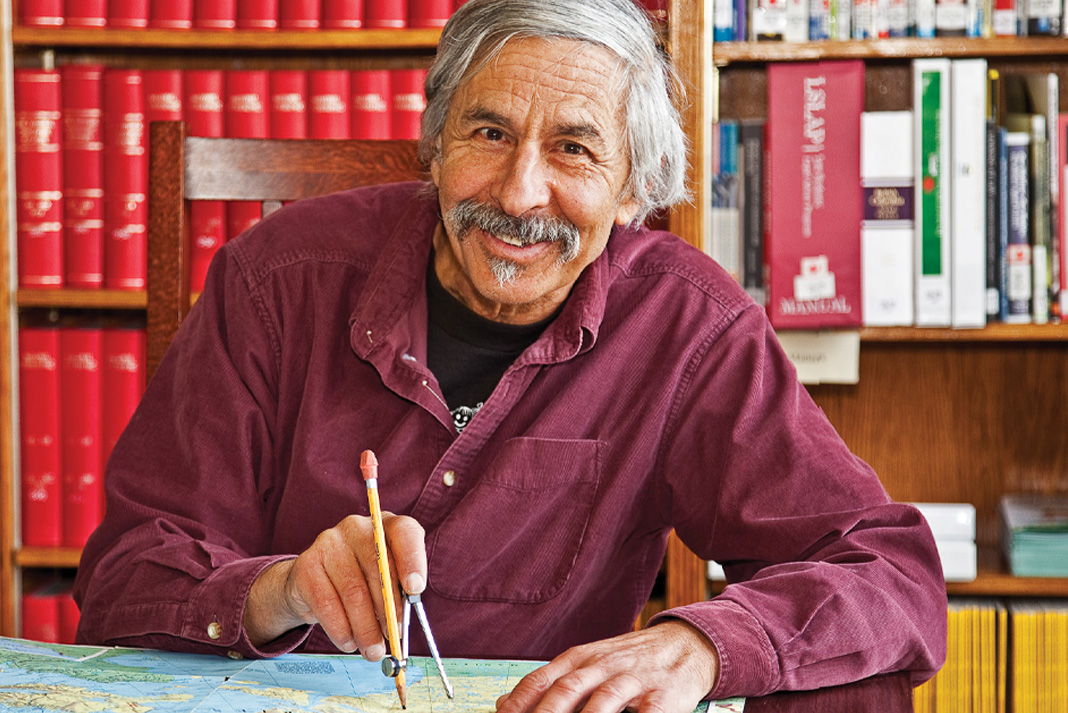

Jon Turk has paddled around Cape Horn, across the North Pacific, and circumnavigated Ellesmere Island. Nowadays, he splits his time between summers in Oregon and winters living out of his van in Arizona, mountain biking every day.

Mind over muscle. | Feature photo: John Webster

This article was published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was published in Issue 73 of Paddling Magazine.