It was our third consecutive lunch of pitas and cheese and we were ready for a distraction. We had pulled up at a narrows about two-thirds of the way down Nunavut’s Coppermine River. The bank on the far side was splattered with head-high willow shrubs and Barb was adamant that there was a caribou grazing among them.

“There,” she said, “just to the left of the little clearing.”

The rest of us munched away, squinting across the river and assuring her we also saw it before realizing what we thought were antlers were just another pair of willow branches.

This went on for 15 minutes, until the pitas were put away for another day, before Mike declared, “It must be a caribou. I can smell it.”

Mike has admirable olfactory abilities, but this was too much. I was about to suggest he was smelling himself when I caught a whiff of what I imagined caribou breath must smell like.

Ally turned around and laughed. Not 20 meters behind us four caribou were mowing down tufts of lichen. We could see every whisker, and hear every gum smack—I had assumed the noise was Mike eating dessert. It’s a good thing we had a large store of pitas, because if we had been relying on keen senses to deliver us food from the land we would have gone hungry.

I couldn’t help but feel out of my element up there. The conventions that time and space follow down south, even on a remote river in the boreal, have no purchase in the Arctic. With the land frozen so much of the year, cycles such as growth and decay grind to a crawl while seasonal imperatives like spring runoffs and animal migrations take on a determined frenzy. It is hard to know what to expect, even hard to know how to adjust your eyes to a landscape that is so barren and hard to read it turns what you thought would be a half-hour hike into a half-day trek.

If you gotta go, go now

That was 10 years ago, and I haven’t been back to the Arctic, a fact that hit me in the gut last week when a couple I know asked me out for a beer and counsel about their plan to paddle the Coppermine.

They were nervous, and had reason to be. They had paddled a handful of rivers, but their whitewater history wasn’t one that begged for a biography. The weather in late August could well be punishing. With only one canoe in their party they would have no one to collect pieces for them after a dump.

As we batted around these caveats I couldn’t help but wonder if I was erring on the side of caution so I would feel better about my inability to muster a return trip above the 66th parallel.

As we often recount in these pages—call it our editorial mission—paddling trips on the whole are getting shorter and shorter. Fewer people are making the sort of time commitment needed to do extraordinary trips. Everyone has reasons. I know I have mine. I just don’t know if they are good enough.

My friends emailed me last week to tell me they had weighed the risks and had decided to paddle the Coppermine. They may become stormbound for a few days. They may dump and lose equipment—or worse. One fate that won’t befall them, however, is they’ll never have to sit on a patio sipping a beer and mumbling sorry excuses for how they didn’t go north that summer because they were too busy.

Recirc celebrates our favorite stories from the first 25 years of Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots magazines. Author Ian Merringer was the editor of Canoeroots when this article ran in 2006. In 2022, Ian enjoyed a couple glorious weeks running northern B.C.’s Stikine River.

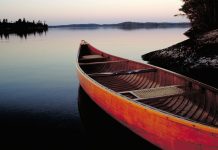

To the polar sea. | Feature photo: François Léger-Savard

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.