On June 14, 1974, my grandma Glady dropped her two sons off at a marina in the Puget Sound. They loaded gear into homemade woodstrip canoes and pushed off into the cold, black water. Decades later, Grandma told me as she watched them disappear into the fog, she wondered if she would ever see her boys again.

My dad, Alan, and his best friend and younger brother, Andy, had been planning this trip for years. They were climbers, mountaineers and fishermen. Before leaving college and entering what they remember calling “the real world,” they wanted one last adventure—an experience truly unknown and challenging; something beautiful they could share as brothers, and with my dad’s girlfriend, Sara, who would later become his wife and my mother, and a small band of college friends.

After my dad finished college, he and my uncle built their own canoes in a college basement, launched them into the Pacific, and became some of the first people in recent history to canoe the Inland Passage from Vancouver to Alaska.

Their story became a legend in my family. One of the original boats still hangs in my parent’s garage. My brother, Ben, and I grew up paddling the old canoe—fishing from it in the Pacific Northwest and beating it up in eastern rivers, like the Shenandoah. As we reeled in fish and cut through waterways, we couldn’t help but marvel at the craft our dad built and wonder what the 1974 adventure was actually like.

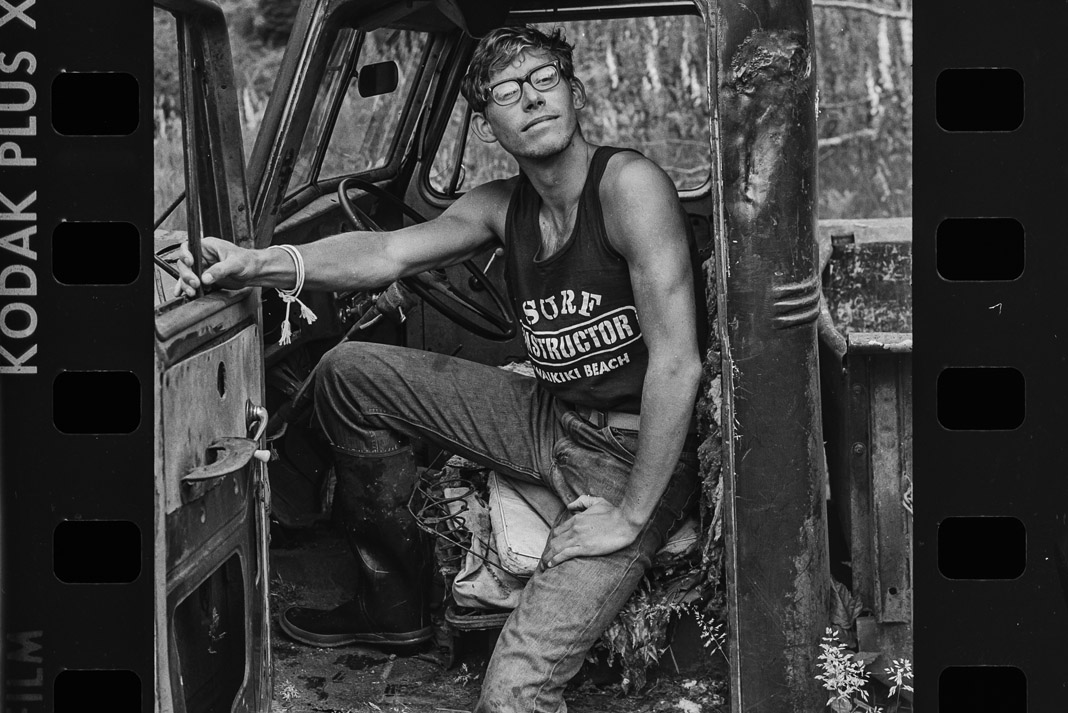

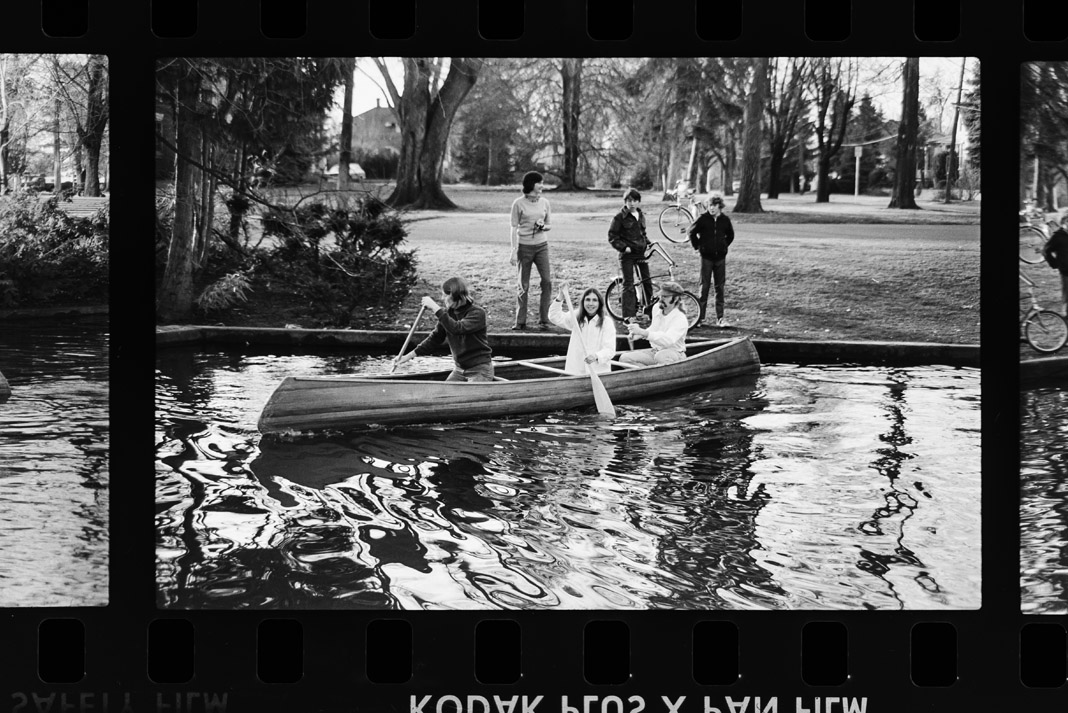

When I was 16, I unearthed a dusty cardboard box behind my dad’s CDs and cassette tapes. Carelessly written on the top of the box were the words, Canoe Trip. The images and film negatives I found inside painted vivid pictures of the 1974 legend—a story of risk, naysayers and adventure. I studied the photographs countless times, mesmerized by images of my 20-year-old parents on the adventure of a lifetime.

Looking back now, almost two decades after finding the images, I’m certain the story of my parents’ journey on the Inside Passage shaped my life choices. How could a journey I never directly experienced have had such a profound impact on me?

Before I could answer this question, I needed to understand what really happened in 1974. And so, for nearly a year, I worked on a documentary about their legendary canoe trip. In the process, I learned volumes about the real journey, my parents and myself.

The story started in 1970. After my dad finished high school, he got a job as a deckhand on a yacht called the Thea Foss, taking guests up and down the Inside Passage, a labyrinth of straits and islands extending from Washington State up the coast of British Columbia and well into Alaska. Stuck on the boat, he watched the coastline pass by and dreamed of fishing and camping along its banks.

His summer experience sowed the seed of a grand idea to canoe the entire coastal waterway. He rushed home from his summer job to share this dream with his younger brother, Andy.My Dad and Andy had a unique relationship as brothers. Close in age, they were best friends throughout childhood and when they went off to university at Whitman College they roomed together.

As early adopters of outdoor adventure, they spent their weekends climbing, camping, fishing and ski-mountaineering in the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. Together, they set a goal of embarking on a journey along the Inside Passage just after my dad graduated from college and before medical school consumed him. The only obstacles standing in their way were a lack of canoes and empty pockets.

Determined to make this trip a reality, they found a man in Bellingham, Washington who shared building plans. For the last six months of university, the duo worked every night in the college art building, sawing, sanding, bending and varnishing. With $500 and a lot of elbow grease, they built three gleaming cedarstrip canoes before graduating.

At the time, only a few people had ever canoed the entire coastline, and there was virtually no information available. During the building process, my dad and Andy sent letters to fishermen, loggers, writers, homesteaders and the Forest Service—anyone and everyone they could think of who lived along the coast and could give them advice about canoeing the Passage.

The letters returned were almost unanimously apocalyptic. “Go home and sell your canoes,” they read. “You’re going to kill yourselves,” wrote another. “People go down in big boats on those waterways. Why are you going in a canoe?” Letter after letter returned, urging them not to do it. Finally, just a few weeks before they were planning to leave, one letter returned with the response they were waiting for. It began, “Do it. It’ll be the best trip of your life.”

At the time, my dad was dating a Wellesley college girl named Sara, who would eventually become my mother. They had been together for about a year, and he decided this canoe trip would be a good opportunity to get to know each other better. As an invitation, he sent her a survival kit filled with trinkets and tools he said would sustain her during the voyage. She accepted without hesitation. Soon after her parents sent her to a psychiatrist to attempt to talk her out of going.

As the story goes, by the time their sessions were over, the psychiatrist wanted to join the expedition.

On June 14, 1974, my 20-year-old father, mother and uncle, along with a small crew of their friends, launched their three homemade canoes into the Pacific and began an eight-week journey along the Inside Passage.

For the next two months, they paddled, fished and camped in one of North America’s wildest landscapes. After their adventures along the coast, they returned home as different people. The canoe trip had changed them, and the story of the grand adventure lived on long after summer faded. Over the next 40 years, tales from their trip were told, and retold. Through a game of telephone and the metamorphosis of aging memories, the story of their adventure became morphed, exaggerated, forgotten and remembered. By the time I became an adult, it was hard for me to separate fact from legend. In my mind, and even in the minds of my parents, they had returned home upon the completion of their intended journey. But as a kid you never really get the full story.

Some of the group needed to go back to college and had enough, while others wanted to continue on to Juneau, their intended destination. They had never completed the original trip as intended.

In September 2015, as we prepared centerpieces for the guest tables at my wedding, my uncle Andy told me by the time the group reached Ketchikan, about 800 miles from their starting point, the crew was divided. Some of the group needed to go back to college and had enough, while others wanted to continue on to Juneau, their intended destination. They had never completed the original trip as intended.

When my dad and Andy started this trip, they were young men with endless possibilities in their lives. Now, 43 years later, they are both nearing the ends of their careers, with more time behind them than ahead. But they still had at least one big adventure left in them. On my wedding day, my brother, Andy, my dad and I made a plan. We decided to refurbish the canoes, return to the Inside Passage and complete the journey through the Pacific Northwest that had shaped them so profoundly as young men.

Our first challenge was getting the four-decade-old canoes ready. When the crew returned home from Alaska in 1974, one canoe went with my parents, one with Andy, and the third was left at my grandparents’ house. Each canoe took on a life of its own. Andy became a professional adventure journalist, taking his canoe on even more epic journeys in places like the Yukon and on the Peace River. The canoe in my grandparents’ house became the Puget Sound fishing vessel on family visits. And the canoe my parents kept became a cornerstone of our childhood adventures. These boats were old, and needed work before they could complete the journey they were intended for.

It took a week to repair two of the canoes. When ready, the four of us ferried for two days from Bellingham, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska. Our aim was to fulfill the original 1974 goal of reaching Juneau, a 300-mile paddle from Ketchikan.

The day we arrived in Ketchikan the rain poured and the wind howled. After just a few hours of paddling up the Tongass Narrows, everything and everyone was soaked. We were in the water for less than five hours before the weather turned and forced us to land on Gravian Island. We stayed there for two days, stranded by wind and high seas. Finally, the sun came out and we continued north.

I was moved by the beauty and richness of the landscape. Every day, humpback whales breached around us. Pods of harbor porpoises rounded our canoes. Sea lions appeared suddenly around our boats, only to disappear a moment later and bark in the distance. Mink ate the many fish carcasses we disposed of after dining on the spoils of our outrageously productive fishing efforts. Evidence of bears was common and once, a young brown bear paraded through our camp, inspecting our canoes before entering the channel and swimming a half-mile to the other side. Even as a wildlife filmmaker, I have rarely seen such abundance.

As the days and nights melted into one another, and time disappeared, we shared stories, catching up on years of our busy, distant lives.

A few days into the trip, as we paddled steadily through this remarkable landscape, Ben and I realized this was the longest time we had spent together since he left home for college 18 years earlier. For my dad and Andy, this was the longest they had spent together since the 1974 canoe trip, 43 years earlier. As the days and nights melted into one another, and time disappeared, we shared stories, catching up on years of our busy, distant lives.

After almost two weeks on the water, we entered the Zimovia Strait, camping on Etlin Island for several days before arriving in Wrangell, where my brother and I would dock our canoe and take the ferry south, leaving our father and Andy to complete the last stretch on their own.

As I watched my dad and Andy paddle off into the distance to finish a journey they started 43 years earlier, I reflected on how the story of their original 1974 canoe trip, an expedition I never experienced, had impacted me so profoundly. How the stories we tell and the stories we remember are reflections of who we see ourselves to be.

As children, we don’t have our own stories yet, so maybe we adopt the ones we’re told that most resonate with who we want to be. My parent’s 1974 canoe adventure had been one of those stories.

From an early age, it was infused into my identity, shaping who I thought my parents were, and who I wanted to become. Now, as a father myself, I have many of my own stories to tell. And at the top of the list is an adventure along the Inside Passage that started in 1974 and ended in 2017.

Nate Dappen is an award-winning photographer and filmmaker based in New Jersey. His images, films, books and other projects have been featured by National Geographic, Vogue, The Washington Post, Scientific American, The Guardian and World Wildlife Fund. Watch his film inspired by this adventure below.