I turned right onto the Liard Highway. I’d already been driving north for two days toward the British Columbia-Northwest Territories border. At the border, the blacktop turns to gravel. On the last lonely 300-kilometer stretch of nowhere, I met only one other vehicle. A white pickup truck with a crew barreling faster than whatever the speed limit should have been getting the hell out of some work camp for the weekend.

I drove through a forest fire burning on either side of the road. I waited for a herd of bison to lumber to the shoulders. I needed to drive most of the night, so by morning, I’d get to make my last turn onto the Mackenzie Highway toward the ferry, which crosses the Liard River. From there, it’s only another 10 minutes to where the road ends, literally, at Fort Simpson. Tomorrow, I’d meet our guides and other guests, and we’d fly even farther north for two weeks together on the South Nahanni River.

A new generation is shaping the future of the Nahanni River

Sitting round the dining room table at the Mackenzie Rest Inn, we took turns introducing ourselves.

Rick was the only other whitewater paddler in our group and was the only other one to drive to Fort Simpson. As a retired U.S. Army colonel, Rick had the time for the six-day road trip from his cabin in northern Wisconsin. The rest of our group arrived on commercial flights routed through Edmonton or Yellowknife.

Kirk and Alanna had bounced around North America, Kirk as a railroader, while Alanna raised their family. Now retired, they travel and lead lakewater canoe trips for international students. Kirk has been dreaming of the Nahanni since he was a boy going to outdoor shows with his father.

Andy’s wife died earlier this year and he has recently been diagnosed with cancer. He wasn’t sure how many big adventures he had left. In Andy’s canoe will be his classmate Paul, a retired finance guy from Ontario. Paul is here for his university buddy. He fessed up early that he hadn’t done anything like this before, as if his crisp new outdoorsy clothes didn’t give it away. He promised to call home every day on a satellite phone to reassure his wife he hadn’t been eaten by bears or sucked from his canoe in big rapids.

The job of looking after Paul and the rest of us falls upon our two guides. Claire Lunen is a summer camp kid with a wild nest of curly hair and an infectious, cackly laugh. Our lead guide is 19-year-old Doug. Doug is my son. He and I have been playing in whitewater together since he was a toddler and I was a wilderness guide. It was his turn to take me down a river. This was his last trip of the summer; perhaps the last, after five summers guiding on northern rivers, before getting serious about an engineering degree.

As we passed the trays of cold cuts, Doug and Claire tell us most Black Feather guests do this northern trip first. It’s the 337-kilometer section of the South Nahanni River that everybody just calls the Nahanni. The scenery is spectacular. The whitewater should be manageable for a crew like ours. The Nahanni, they say, is either a lifelong dream and a box checked in someone’s life list, or it’s a gateway drug that hooks them on a lifetime of northern rivers.

After a two-hour floatplane ride farther north over the Mackenzie Mountains, our trip begins at Rabbitkettle Lake. From here, it’s a few days of swifty, non-technical class I whitewater, perfect for learning strokes and getting rid of our wobbles in the canoes. Unlike canoe trips you probably remember—or dread—from summer camp, most of the popular northern rivers have few portages. No humping canoes and gear from lake to lake, just around big rapids or waterfalls too big to paddle.

Right on schedule, we roll into Virginia Falls on our fourth day. It is our only portage, and it’s a doozy. The falls are twice the height of Niagara Falls and more impressive. The flow is divided around a toothy spire called Mason Rock. Mason Rock is named after Bill Mason, the canoeist, wilderness artist and filmmaker whose books and films captured the adventurous spirit of those of us growing up in the 1970s and 80s. We read his books, watched his films and promised ourselves that someday we’d paddle the Nahanni.

In 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, with presumably less time to kill than we had, landed above and carried his canoe the 1,300 meters around Virginia Falls. I remember a black-and-white photograph of him standing below the falls where we did—where I’m sure everyone does—for a group photo. Fifty years later, nothing in the background is noticeably different, in part thanks to Trudeau.

You either look at the 96-meter drop of Virginia Falls for its natural beauty, like UNESCO did when it made the South Nahanni River a World Heritage Site, or you see its incredible hydroelectric potential. In 1972, with Trudeau’s influence back in Ottawa, the initial Nahanni River Park Reserve was established, forever protecting this magnificent group photo backdrop and Canada’s Grand Canyon below.

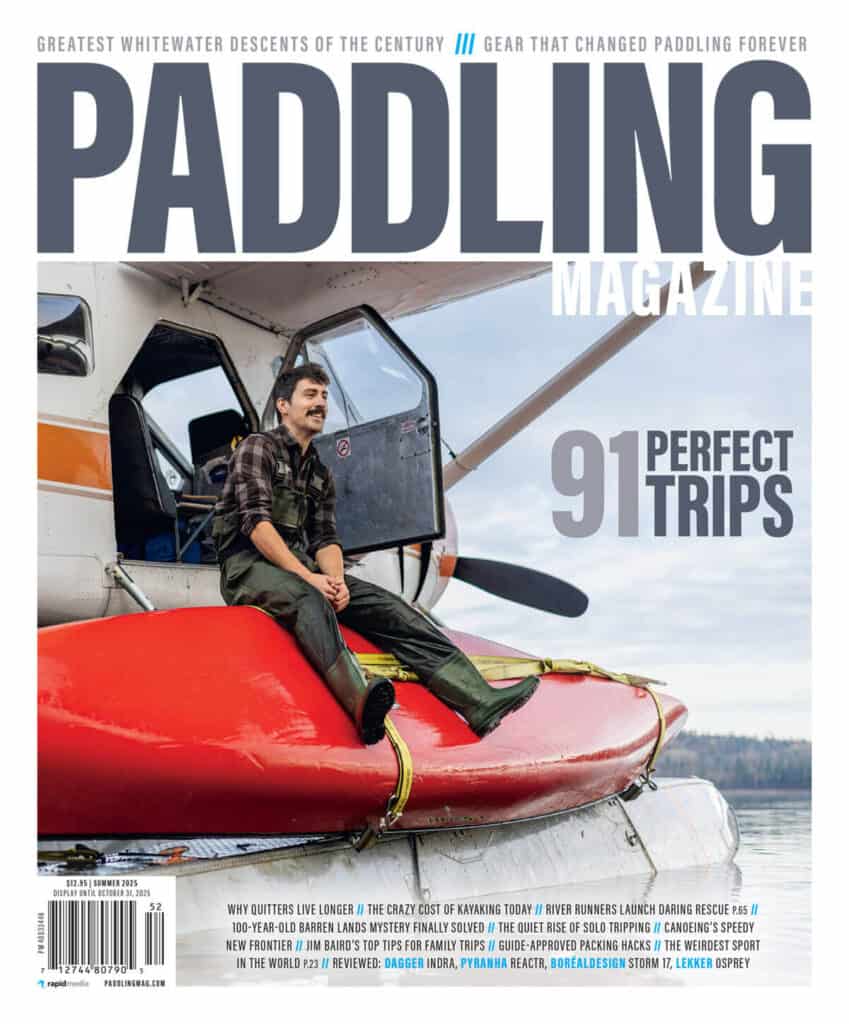

Below the falls, with Doug in the lead boat and Claire as sweep, we shoved our canoes into the class II whitewater Paul’s wife was at home worried sick about. It’s challenging to capture images from the stern of a bobbing canoe. The grandeur of 1,000-meter-high canyon walls doesn’t come through on a waterproof action camera the size of a Twinkie. How did early gold prospectors ever travel up this river, I wondered. Has anyone bothered since the invention of bush planes on floats? I doubt it.

While we were on the South Nahanni River, the federal and provincial governments were engaged in negotiations with the Dehcho First Nations and other Indigenous groups regarding unresolved land claims. These things move slowly.

Meanwhile, the park reserve is being cooperatively managed through a joint initiative between Parks Canada and the Dehcho First Nations. The focus is on protecting the ecological and cultural integrity of the area. An important evolution of the management plan is the continued integration of Dene culture and traditional knowledge into our visitor experience.

Over the last decade, the 50-year-old guiding companies operating in the Nahanni National Park Reserve have been changing hands. The new generation of owners and guides who now hold the commercial licences is continuing longtime traditions while incorporating new ways to provide more cultural experiences.

In Fort Simpson, before every Black Feather trip, K’iyeli, an Indigenous business run by locals Gilbert and Marie-Jane Cazon, provides a Dene welcome session and blessing. They have also worked with Black Feather guides during staff training. New owners of Black Feather, Ken and Stef MacDiarmid, expect to see even more integrated Indigenous culture, tourism employment and ownership of businesses providing services.

Tetlit Gwich’in river guide Bobbi Rose Koe and Nahanni River Adventures owner and guide Joel Hibbard cofounded Dinjii Zhuh Adventures and created the Indigenous Youth River Guide Training program. For three years, the program has been teaching Indigenous youth flatwater and whitewater canoeing, wilderness medicine and whitewater rescue training. While the canyons of the South Nahanni River will likely remain unchanged for the next 50 years, the stories told by Nahanni River guides are likely to be different.

On our last night, we camped at Last Chance Beach. The guides call it Last Chance because downstream the river valley opens up and the river braids into many shallow channels. Beyond our high cobblestone and sandy beach, it turns to muddy shorelines with scrubby alders.

Tomorrow we’ll shove off for the last time, pushing toward the Dene community of Nahanni Butte, located at the confluence of the Liard and South Nahanni rivers, and meet our van shuttle back to Fort Simpson.

Around the campfire, Doug and Claire share stories of other trips in the Northwest Territories. The Mountain River has the most exciting whitewater, Doug says. Claire hopes she’ll get to do a trip on the Keele next summer. Also on their lists to paddle are the South Nahanni River headwaters, known as the Moose Ponds, and the tributary rivers, Little Nahanni and Broken Skull.

Doug pulls out a stashed bottle of single malt Scotch for a toast. The shy banter around the dining room table at the Mackenzie Rest Inn has evolved into aggressive chirping and inside jokes no one back in the real world would think are funny. You had to be there, as they say. We finished the bottle.

Later that night, after the sun had finally set, I crawled out of my tent with a bladder fed too much whiskey. For the first time in two weeks, across the entire sky, the northern lights shimmered and danced. I rattled tents until everyone was out, wandering around in their underwear. It was our last chance.

Science nerds say the show is caused by magnetic storms triggered by explosions on the sun carried to us by solar wind. The Dene people, however, believe the aurora is a fire built by the world’s Creator. The colors in the night sky are there to remind us that the Creator is still watching over us. Watching over the South Nahanni River.

Eventually, the Creator must have been satisfied with what he’d seen and snuffed out the fire in the sky. I crawled back into my tent. In my journal I checked the Nahanni River off my list and added the Mountain. Then I fell asleep.

Scott MacGregor is the founder of Paddling Magazine.

Camping above Virginia Falls allowed us to break up the only portage over two days. Switchbacks descend into Fourth Canyon where the real whitewater begins. | Feature photo: Scott MacGregor

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

I simply do not know how to afford guided trip after guided trip up north as some seem to indulge themselves. Maybe, it’s more of an issue of justification: There are many folks in this world who could use some of the money spent on these very expensive trips. That said I hope to do the Nahanni myself before I age out. I have led many northern trips on many northern rivers; ironically, I always thought the Nahanni was too crowded, so it remains on my list.

Incidentally, the trips I did were anywhere from two weeks to six weeks. The participants were mainly young people raised in poverty. My intention was to teach them how to live in the wilderness, so our packs were light (1 1/2 – 2 lbs of food per day, for example). We spent at least a year working on whitewater, portaging, camping, backpacking, rescue and environmental skills prior to their first trip. Each trip was done for a fraction of what the three companies you mentioned charge.

By the way, I also did mountaineering, backpacking, sailing and kayak trips in a similar vein. All back in the 70s and 80s.

And guess what, none of those trips required whisky at the end.

I did try out one of the companies shorter trips – in Quebec – and was astounded by the weight of the food and cooking gear. There were several portages. This was not a trip for those experienced in wilderness travel or those who wanted to learn about wilderness travel.

There were also equipment failures which I won’t get into except to say the canoes were not big enough to carry all the gear.

Lots of goals as I tip toe into my eighth decade. the biggest? Find backcountry ski lodges that do not require helicopter access (can you spell Climate Change?) but still pamper.

By the way, on the topic of important and overlooked skills in WW kayaking, I once paddled (solo canoes) with two well-known and world class paddlers. We came to a hole which, for some reason I cannot explain, I decided to jump into first. My roll was about 70% then in a canoe…I swam. Both of these renowned paddlers threw their bags toward me …and missed!!!!! I took a very long and dangerous swim.

So when it came to their turn, each swam also (a huge surprise to all of us because their canoe rolls prior to this particular hole were 100%)). I put my rope into their hands. Later, they asked why I was so good with a throw bag. I hope you know what I said to them: “I practised”. It’s not rocket science. During each and every spring you throw hundreds of times (just as each and every fall you run many transceiver practices). It’s what you do!!!