In the never-setting July sun of the Arctic summer, West Hansen and Jeff Wueste paddle their tandem Seaward Passat with euphoric momentum across a frigid, but ice-free stretch of Lancaster Sound toward Somerset Island. Nearby, in another tandem kayak, are their expedition partners Eileen Visser and Mark Agnew. Together, the four are the Arctic Cowboys. Seventy days from now they will complete a momentous first in paddling: they will become the first known people to traverse the Northwest Passage under human power alone within a single season. But on this day, 10 days into their attempt, the expedition party is enjoying a rarity—optimum conditions have allowed them to cover 45 miles of a 1,600-mile journey. Hansen and Wueste have cause yet for more optimism.

Just a year earlier at this point, they ended their first campaign to paddle the Northwest Passage. From here on, they’ll be paddling new waters. But ice-free waters and light winds are as easy a day as the Northwest Passage is going to give.

Paddling the Northwest Passage

It’s for good reason no one has paddled the entirety of the Passage in a single year up until now. The Northwest Passage is a series of waterways mazing through a collection of islands that make up the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. For over two-thirds of the year, all or most of the waterways are frozen over with sea ice. The window to successfully pass through the Passage by water is brief—the summer melt season is barely three months.

Since the 1700s, European sailors have recorded their attempts to find and use the Passage as a maritime transportation and trading route. Roald Amundsen and his expedition crew were the first Europeans to transit the Passage by ship in 1906. To this day, even the number of powered vessels that traverse the Passage each year remains small, and the topic of it becoming a major shipping route is one of the most substantial conversations about the Arctic.

The Arctic Cowboys aren’t the first to try paddling it, though. Over the past 40 years, more than 20 attempts have been made to paddle or row the Northwest Passage, and virtually all have failed.

The most notable successful attempt was made by French rower Charles Hedrich, who set out from Alaska in 2013. He arrived in Pond Inlet, Nunavut two years later, in September 2015—making him the first to accomplish the waterway by human power alone. Still, it took multiple years, and Hedrich’s stopping place is argued to be just short of the official geographic mark by about 40 miles.

Of course, alongside the nature of records and exploration, the Inuit people have lived in the Arctic for millennia, using paddle craft and sleds as means of travel. However, there is no evidence suggesting a transit by kayak occurred across the Passage.

Ice is what’s kept human travel through the Passage constrained, but this is changing. According to NASA, the average duration of the Arctic melt season is gradually increasing, and sea ice isn’t replenishing to the same levels in the winter. These shifts to the landscape have now perhaps reached a significant threshold—providing enough time for a kayak to make the journey.

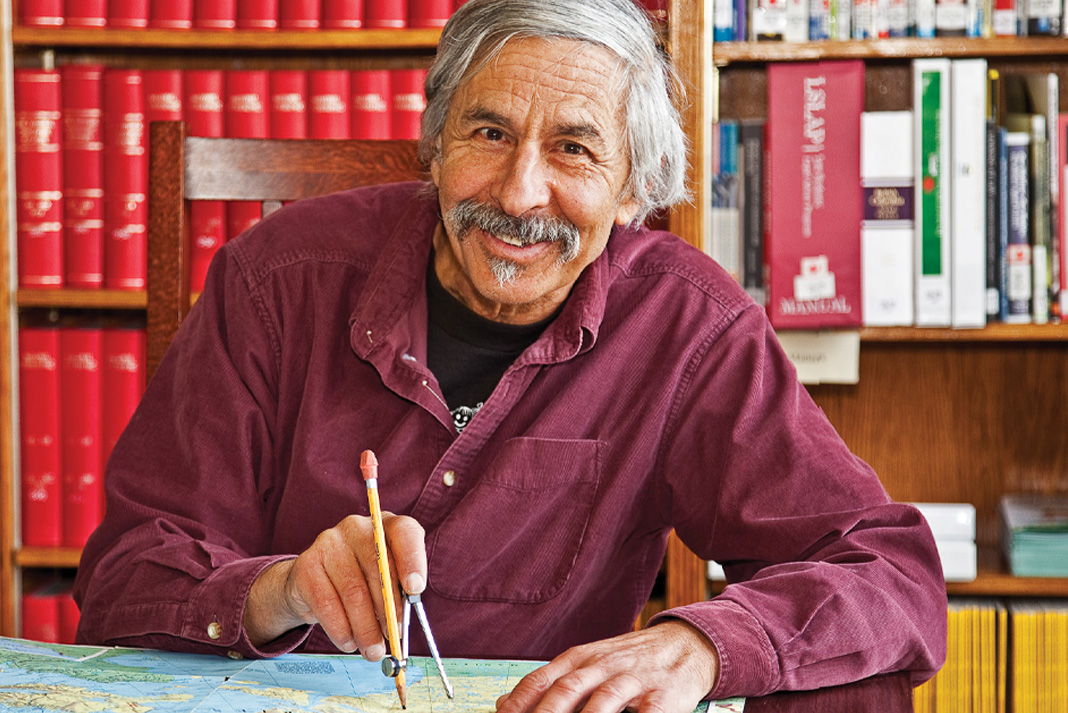

West Hansen and the Arctic Cowboys

West Hansen is no stranger to endeavors of this magnitude. A social worker by day with a full resume of endurance paddling races, the 61-year-old expedition leader of the Arctic Cowboys has been part of multiple historic paddling expeditions. In 2012, he was a member of the team that was the first to paddle the Amazon River 4,200 miles from a source in the Peruvian Andes to the Atlantic Ocean. In 2014, he was also on the team that was the first to complete the 2,100-mile length of the Volga River in Russia—the longest river in Europe. Jeff Wueste, two years older, has been one of his accomplices each time.

It was over five years ago Hansen started putting the pieces together on the coveted transportation route through the Arctic.

“I was reading a book by a friend of mine, Buddy Levy, on historic Arctic expeditions. It triggered me to do some research on modern expeditions,” Hansen recalls of the self-discovery building toward the attempt. “I realized no one had actually successfully navigated the Northwest Passage under their own power. It’s something that hadn’t been done, which I’m attracted to, and it’s a place most people haven’t been to or seen. So those components came together and we started putting it together.”

The Arctic Cowboys made their first attempt at the start of August 2022. Hansen, Wueste and experienced long-distance paddle racer Rebekah Feaster set out from Bylot Island, just north of Baffin Island at the eastern entrance of the Passage. Within five days on the water, Feaster made the decision not to continue. Two hundred miles into the trip, Hansen and Wueste decided the same and aborted the 2022 expedition in Arctic Bay.

In July of 2023, Hansen and Wueste returned to Bylot Island—a month earlier than the previous year, and with two new Arctic Cowboys: Eileen Visser, a professor and endurance paddler, and Mark Agnew, a British adventurer and writer. The Arctic Cowboys set out from Bylot determined to finish what they barely scratched the surface of in 2022.

Bathurst or bust

They weren’t the only paddlers making a bid at the Passage in the summer of 2023. There were at least four teams making an attempt, including two rowing teams and standup paddleboarder Karl Kruger. Each of these teams would end their campaigns by September.

After rounding Somerset Island and leaving Lancaster Sound in late July, the Arctic Cowboys had 70 days ahead of them. Seventy days of close calls with icebergs and tidal straits. Of nearly daily encounters with polar bears, and nights under mesmerizing skies. Of days windbound at camp with subfreezing temperatures. And near the end, as they exited Amundsen Gulf, heaving seas with 20-foot breakers.

On October 8, 2023, the Arctic Cowboys reached Cape Bathurst and the Beaufort Sea—a point along the geographic line recognized by the International Hydrographic Organization as the western terminus of the Northwest Passage. They had done it, they had become the first to paddle the Arctic passageway within a single year.

You could easily imagine the expedition instantaneously ends there, but it doesn’t. Like summiting a mountain, the quest to get home is just as, if not more, dangerous.

They remained in the Arctic, traversing a freezing landscape as winter roared in, looking for their way out. They would have to make it another three days and 50 miles south to meet a bush pilot on Nicholson Island. Then wait in nervous anticipation for their lift to a more temperate climate where they could truly soak in the revelry of what they had accomplished.

When we called West Hansen, he and his team were sitting in a hotel room in Saskatchewan, 10 days removed from having crossed Cape Bathurst. Exhausted, the tips of his fingers recovering from frostbite, and dreaming of a plate of barbecue 1,700 miles away in his home city of Austin, Texas, the paddler graciously shared some thoughts from the journey.

An interview with Arctic Cowboys expedition leader West Hansen

Paddling Magazine: You attempted the Northwest Passage last year and decided to abort. This time around you passed that mark around mid- to late July and were successful in completing the expedition. What was different this year that enabled you and your crew to complete the Passage?

West Hansen: The learning curve from last year was huge. You know, there’s nothing better than actually doing what you’re going to do. We learned so much in the month that we spent out here last year. We could see that we needed to not rely on a resupply. We had a resupply itself last year that fell through, and that shut everything down. We needed to be able to be self-sustaining in tandem boats, which we would be able to use in rougher water and also carry more gear.

Also, we started earlier this year than we did last year. It was a lot dicier. We were starting while the sea ice was still out there, but that gave us the leg up to have more time in the Passage to complete the expedition.

PM: So you carried everything you needed for the entire expedition?

Hansen: We carried all of our food and gear throughout the entire Northwest Passage. The only resupply we had was at the town of Cambridge Bay. For this resupply, we shipped cartons of dehydrated food packs to someone we found on Facebook, who volunteered to store the supplies until we showed up. Additionally, we had our expedition manager ship us some additional supplies. Unfortunately, the person in Cambridge Bay whom we trusted to hold our stuff opened the boxes and ate a lot of our food, so we had to purchase additional food in Cambridge Bay. This was our only resupply point. We had no support team, other than Barbara Edington and Tom McGuire, who were back in Texas managing the website and other logistics.

PM: Were there aspects of the Passage that surprised you? That perhaps you and the team couldn’t have expected?

Hansen: Several. One of which is that we saw polar bears every day until we made it to Cambridge Bay. And I’m not talking about every other day, or two or three times a week. No, every day we saw polar bears. We knew there’d be polar bears. We were prepared for them. We had all the appropriate gear to deter polar bears. It’s just amazing to see polar bears and polar bear cubs every stinking day. So we got used to that.

PM: They are obviously some big animals that could do whatever they wish, but did you reach a point where that situation felt normalized?

Hansen: Well, we weren’t afraid of them after a while because we learned they were very afraid of us. They always run away.

We had flares, we had bear bangers, we had shotguns, we had a rifle, we had movement sensors that we put around the tent. We had bear spray. But usually, if you yelled at them, they’d run away.

They really were afraid of us. And so that made us a little bit more comfortable. But yeah we got a bit more used to them, that’s for sure.

PM: So if not the bears, what would you consider one of the most dangerous moments of the expedition?

Hansen: Bellot Strait was a horrendous incident. We waited there for three days for the wind to calm down. And then the information we were provided about the tidal flow through the strait was 180 degrees wrong, unfortunately. So when we started into the skinniest portion of it, the water turned and started coming toward us, including these giant floes of ice. We had to negotiate our way through this ice that was going 10 miles an hour. We had to cross about 400 yards of very strong eddies, whirlpools and this fast-moving ice in order to get to the safety of the shore. And that was pretty scary. Fortunately, we made it.

Then we waited about six hours after that for the tide to calm down, and were able to progress safely through the entire strait.

PM: It seemed it never let up for you. Toward the end of the trip, we were all following your team and you were getting bogged down. Could you tell us about that home stretch and whether you knew you were going to make Cape Bathurst? Or was there a time you thought you may have to end the campaign again?

Hansen: The last half, from Cambridge Bay to the Beaufort Sea, the farther along we went, the more down days we had because of weather, and that was very, very frustrating. We knew we’d have that. We expected it to a certain extent. But really, you know, paddling three days and sitting in the tent five days was extremely frustrating.

At the same time, I had to be prudent. I didn’t want to get the team out there in some conditions that were too rough for their abilities and risk the entire expedition on a rescue or something like that.

We never thought we’d have to abort the expedition ever. Some teammates did, but I didn’t. I always felt whatever the conditions are, I know we can get through them. And so I felt good about that. But it was very, very frustrating toward the end with the number of bad weather days compared to the days we could make forward progress. That was the roughest part. But once again, we knew it was coming.

I figured also, with the classic expeditions out there, like climbing Everest and crossing the poles, those explorers had huge down days just waiting out the weather. I knew this was no different. Down days were just part and parcel to the experience.

PM: You’re referencing Everest there, and waiting for weather. Was there a seasonal window also playing a factor? A timeframe you had to make to be successful?

Hansen: We knew winter was coming. There’s not a set date that says, okay, this is winter. We didn’t have that date. And I don’t think anybody does. I mean, right now in the Franklin Bay over to Cape Bathurst down into the Beaufort Sea, there are 100-kilometer winds and storms. It’s pretty bad. Maybe five days from now it might be calm enough to paddle so long as the sea isn’t frozen over. I was always figuring, as long as the sea isn’t frozen over, then we have our window.

Those snowstorms in the last two weeks were pretty rough. We woke up with snow piled against the tent, three or four feet high. We couldn’t sleep some nights because the wind was howling, 40-mile-an-hour wind. It was pretty rough in some of those snowstorms, but nothing that would’ve caused us to stop.

There’s the other issue of not really having another option. What are you going to do? You know, stop and call for a rescue because the weather’s bad? No. We didn’t really have an option. We had to keep going.

PM: After enduring and completing the Passage the expedition wasn’t over for you, though.

Hansen: No, we finished the western boundary of the Northwest Passage at Bathurst. And then we arranged for a bush pilot to pick us up at Nicholson Island. That was about 50 miles south.

It took three days of negotiating the weather to get down there. One of those days we just sat in the tent because the snowstorm was just too strong. So we just sat there and let the snow pile up against the tent and just hung out.

PM: That has to feel as if it’s reaching a point of desperation.

Hansen: It was very frustrating. I can assure you. You’re this close, you know. We just needed X amount of hours of clear weather and we could get to the pickup point.

Even at that point, we’re at Nicholson Island and there’s this old abandoned airstrip. The Twin Otter came in to pick us up, and it made about eight or nine passes over this very, very rough runway to see if it was okay. We did not know if it would be picking us up until it actually landed. We thought, “Okay, any minute now, it’s going to turn around and head back. And we’re going have to kayak the final 120 miles in these snowstorms to get out of here.”

PM: That is unnerving, but it couldn’t have all been scary. What were some of the most fascinating parts of paddling the Passage? The reasons to be there?

Hansen: The polar bears were the coolest thing to see. You know, once we figured out they were scared of us. They were very unique animals.

And the stars at night were amazing. Once we started getting nighttime after Cambridge Bay, we could see the Aurora Borealis on a regular basis. And it was south of us, you know, not north. Before the onset of nighttime, when the sun was up 24 hours, at one point we were crossing Prince Regent Inlet. The sun was on the western horizon and it was covered up by clouds, but you could see it. This big red ball in the sky. And on the eastern side of Prince Regent, 40-some-odd miles away, the full moon was at the exact same level in the sky. And it was just huge and bright because it was reflecting the light from the sun. And that was a very magical moment, to see both the sun and the moon, these two huge celestial bodies at the same place, just above the mountains on either side.

The other thing was visiting the same places these historic figures had explored. I’ve done all the research. I’ve read every book I could find on the Golden Age of Exploration and Northwest Passage. Roald Amundsen, I’m obviously a huge fan of his. To see the places he had stayed and had written about and also the Franklin, the Ross expeditions, all through there. They were very specific in their journals. And so I’ve noted that on my maps. And it was just a personal achievement to be in the same places these explorers have been.

PM: Absolutely. And your group has started a new chapter of Arctic travel. Experiencing it yourself, do you see people coming in and paddling this more often—following in your footsteps?

Hansen: I don’t know. My buddy Jeff Wueste and I were just discussing whether this would mean more people would come or, since we had done it, does that mean people are going to stop trying to kayak or row it. I hope people reach out to me, read my book, or watch the documentary we’ll produce, and do sections of it. I think it’s possible someone can do it in a season again with a mimic of a lot of things we did. But I would really hope it opens it up for people to do sections, either supported or unsupported, just to see this gorgeous area.

It’s going to change pretty radically in the next few years. Once the Northwest Passage is predictably open, commercial shipping will increase a hundredfold, because it’s faster and safer to get through the Northwest Passage from Europe to Asia and back than it is to go through the Panama Canal.

Once it is wide open, this entire area of the Northwest Passage is going to be changed. It will be more populated. And it’ll become pretty industrialized. I’m glad we got to see it before that happens. But I also hope, what we did, and what we’ll write about and depict, will help preserve some of the greater aspects of the Passage.

Feature photo: Courtesy West Hansen / Arctic Cowboys

I will bet that after that experience West and Jeff will be glad to be back on the San Marcos and Guadalupe Rivers racing the maraton Texas Water Safari under the blazing June skies of central Texas. The only polar bears they will see will be hallucinations caused by canoeing over 260 miles in a daya and a half (or less.) I admire these guys, but they are even crazier than I am, and that’s pretty crazy.

This team is falsely claiming they completed the “Entire Northwest Passage”. It only takes a few moments to do and internet search to determine what and “Entire Northwest Passage” is. They completed a crossing of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, which is a major accomplishment… but not and “Entire Northwest Passage”.