“I put the student out in front,” explains kayak instructor Dan Dixon. “They lead me down the river, and I let them get into anything I can get them out of.”

Three of us are kayaking down Section 9 of the French Broad, eddy hopping and joking along the way. Going first is Jean-Marc, an adventurer from Mexico City who has worked with Dan for five years. After decades of cenote diving, sailing and car racing, an accident forced Jean-Marc to have several vertebrae fused. So, he sought Dan’s guidance to adapt his paddling.

After a dry summer, the river is low. But Dan believes in getting the most from whatever level he encounters. Spotting some deep current with several mid-river rocks, he calls us over for an exercise. From the top of our eddy, paddle below one rock, loop around another, and return in the fewest strokes possible. After 30 minutes, each of us has reduced our total strokes by half.

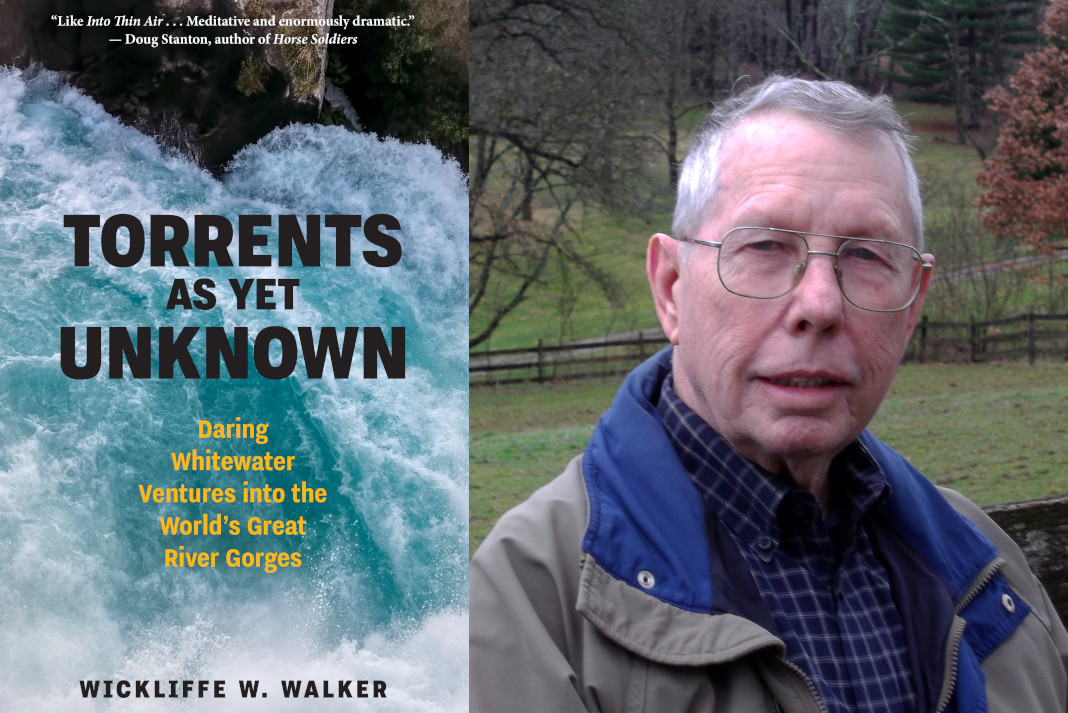

Out in front with kayak instructor Dan Dixon

“I’ve been out there a few times when things went wrong,” Dan later tells me. “Being fully aware of the consequences reinforces the importance of certain skills, like putting everything into make an eddy.”

A few days earlier, I was paddling the Nantahala River, and I ran into Dan when I was taking out at the Nantahala Outdoor Center (NOC). Before we knew it, we’d spent over an hour sharing river stories. When he invited me to tag along for a class, I practically jumped into the Subaru he was driving, with colorful decals celebrating NOC’s 50th anniversary.

Equally impressive, in 2024, Dan will celebrate his own milestone: 40 years with NOC. These days, Dan lives in Ecuador, where he guides paddling trips. But he returns to the NOC Paddling School each summer, primarily as a private instructor. Most of Dan’s students are return clients, and they often seek out his assistance with more complicated situations, like preparing to kayak the Grand Canyon, paddling with disabilities or embarking on expeditions abroad.

In recognition of Dan’s dedication and expertise, NOC named him a Master Instructor about a decade ago, and he’s currently the only staff member to hold the title. Now, Dan’s not necessarily humble, but he doesn’t brag, and he listens just as much as he talks. After hearing some intriguing comments, it took several follow-up conversations with him to learn about his adventurous paddling career.

Pulled around the world of whitewater

As a teenager living in Northern Illinois during the late 1970s, Dan sold some farm animals to buy a 13-foot Hollowform, one of the earliest plastic kayaks. After paddling solo for a year, he befriended some Chicago paddlers. Soon, he was paddling with them from the Midwest to the Southeast and beyond.

“For me, kayaking was about going places that I couldn’t get to other ways,” says Dan. “As my skills grew, the limits started dropping away.”

An American Canoe Association instructor course led Dan to NOC in the early 1980s. While working on the Chattooga River, he earned a nickname that stuck. Back then, like today, Dan’s preferred paddling apparel was a speedo. During that time, there was a movie remake titled Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. The jovial guides believed Dan should have been the lead actor.

“A lot of the nicknames were worse,” recalls Dan. “I got off light.”

As the decade continued, Dan increasingly paddled outside the U.S. First was Canada, where Dan worked on the Ottawa River. Next came Mexico, with months spent zigzagging around in a Datsun hatchback. Later, he paddled the entire Mosquito Coast.

“Nepal was the first big thing,” recalls Dan. After a few months in-country, he was invited to join an NOC commercial kayaking expedition. The guests were Dan’s Chicago friends. He jokes that, since he often rescued them on private trips, why not join up officially as safety boater. The group ran rivers like the Sunkoshi, Seti Gandaki, Marshyangdi and Trishuli. When the guests left, the guides continued exploring, and the waters weren’t the only rough part.

“We were detained on the Tamakoshi,” says Dan in his understated way. “Held for three days and made a break.”

“A break?” I ask. “Like a jailbreak?”

A first descent fortunately avoided

More like a house arrest related to permits, explains Dan. Kayaking was so new, Nepalese tourism officials didn’t know how to respond. Back then, he continues, China had recently opened occupied Tibet to independent travel. The government wanted a huge fee for the first permit to run the Upper Tsangpo. So, Dan and his friend, an NOC guide named Arlene Burns, slipped in by taxi with two kayaks on the roof.

They started near Lhatse, where the Tsangpo was a braided river with class II-III rapids through high-desert valleys. After 100 miles, Arlene left at Shigatse, but Dan continued solo. Eventually, the river gorged up with mostly IVs and some Vs. He portaged once, cold and shivering, over enormous boulders.

Dan was most worried about getting caught. He paddled several times at night to sneak past a guarded bridge and a few Chinese encampments. Upon reaching the Lhasa River, he took out and went up to visit Tibet’s mountainous capital city. When he returned, his boat had been stolen.

“Perhaps luck,” admits Dan, “kept me from running the lower sections.”

Over a decade later, one of those sections—the ferocious Tsangpo Gorge—would drown expedition kayaker Doug Gordon. Four years later, the famous Scott Lindgren-led expedition would spend 30 days making the first successful descent.

Dan originally planned to stay three months in the Himalayas. But nine had passed when he walked into a U.S. consulate and was recognized. He’d been reported missing by his parents, who feared the worst. Distraught, the 24-year-old realized he hadn’t called home in six months. It was the first of two times Dan would be erroneously feared dead while paddling abroad.

Finding Eden and facing disaster

During the 1990s, Dan split time between Costa Rica and NOC. In 1997, he guided his Chicago friends on an exploratory kayak expedition to Ecuador. Immediately, Dan was smitten by the rivers and culture.

“I have a habit of trying to stay longer in places,” says Dan.

In the early 2000s, Dan obtained residency in Ecuador. He and his wife initially lived on the banks of the Rio Tena. But during a harrowing night of flooding in 2010, they had to paddle away from their house and decided to move seven blocks uphill.

In Ecuador, Dan found strong paddlers to explore with. One was a conservation warrior hoping to convince Ecuadorians to preserve their pristine ecological and river resources. Another was a U.S. photographer named Oli, a great athlete with an impressive roll. Together, Dan and Oli began documenting their first descents in the region.

One day, they were exploratory paddling on the Quijos River below San Rafael Falls (which eroded away in 2020). The two had previously scouted by rappelling from the cliffs above. Dan says it wasn’t an overly challenging section, but it was running high. After Oli swam a few times, he seemed off his game. Dan went ahead to mark the take-out eddy, which was just upstream from an un-runnable chasm. As Oli approached, he was deflected off a curler. He flipped on a wave, rolled up and flipped again.

“I knew he was coming out,” says Dan. “So, I went after him.”

Dan got Oli on the back of his boat and aimed for the far shore. But the two were swept over a 10-foot pour-over and went deep into the hydraulic below.

“I felt a tug as my friend was yanked away,” says Dan. “I never saw him again.”

A few weeks later, the American Whitewater Journal erroneously reported that Dan Dixon had drowned that day. A correction came a few months later, along with a promise to improve the criteria for posting an accident report.

Philosophies for a long, happy paddling life

“I want people to have the skills so they can enjoy the sport forever,” says Dan about his teaching philosophy. “When people think they can’t make an eddy, they give up. A lot of times, there’s more opportunities to make it.”

My time with Dan is coming to an end, yet I can tell there are more stories to share. We briefly talk about how he’s managed to have so many remarkable adventures over the years. Paddling skills aside, Dan believes it’s a mix of social awareness and how he responds to situations. When I ask for an example, he recalls a tense moment during his expedition up the Mosquito Coast.

Dan was camping in Nicaragua when, around midnight, a villager entered his tent. The villager had a machete and a request that bordered on a demand: would Dan buy 10 kilos of cocaine?

“Ten kilos!” Dan tells me. “How you respond in a moment like that may dictate whether you live or die.”

Speaking in Spanish that night, Dan thanked the armed villager for the gracious offer. Then Dan diplomatically explained there were several reasons why the deal couldn’t go through. The villager seemed unconvinced until Dan made one particularly reasonable point.

“I don’t have space for it in my kayak.”

Mike Bezemek is an avid paddler of any water that moves. He’s the author of several books, including Paddling the Ozarks, Paddling the John Wesley Powell Route, and Discovering the Outlaw Trail.

Dan is one of many but certainly one of the larger than life, well known and loved NOC instructors.

I have paddled with Dan several times in Ecuador. He is an incredible river guide and even more remarkable man. He knows when I am going to be in trouble in a rapid or with a move before, I even know it. His sixth sense is amazing. I have always valued everything about him, especially his friendship.

I met Greystoke in Tibet. Very glad to learn he’s still alive. Thank you for the good article!

I met Dan on my first Grand Canyon trip in ’89. Hadn’t heard of him before then. He and his then girlfriend arrived in his almost totally rusted out B210. I had hiked into Phantom and joined the trip there. I was told stories of how he had grabbed a rope in his teeth and pulled a loaded, flipped raft to an eddy. Every night he would tell a segment of his trip down the Tsangpo. It was something we soon looked forward to every night. In addition to being a great paddler, Dan is a fabulous storyteller and photographer.