My hand curled comfortably around the paddle shaft, a month’s worth of calluses finding their place for another evening’s work. The blade bit into rippled water and my muscles fell into rhythm. As we moved out from the safety of the cove, we knew we were in for it. Dark sentries of swell marched steadily across the exposed mouth, growing like anthills under time-lapse photography.

The forecast called for a huge northwest sea of three to four metres, with waves up to twice as big on the faces.

Highs and lows in Haida Gwaii

When I’d planned the circumnavigation of Haida Gwaii five months earlier in a skid row diner in Vancouver, I envisioned a journey that would take me away from the crawling city and bring me face to face with raw nature, far from help or hindrance. I wanted to go to a place where I was a mere speck of dust, something that could be absorbed in an instant without the surrounding ecosystem missing a beat. Now the bleak thought squeezed into my brain, “Frank, you should be careful what you ask for.”

We had holed up in Mike Inlet for the afternoon, hoping the building seas would calm. The 4 p.m. forecast on the VHF didn’t bring the news we wanted. But with only six kilometres to go—a mere six kilometres!—we chose to push on to Puffin Cove anyway.

Puffin Cove is where local legends Neil and Betty Carey built a cabin and homestead that they lived in from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Keith had read Neil’s book Puffin Cove and was eager to see the place. Todd had read Bijaboji, Betty’s account of her 1930s canoe trip up the Inside Passage, and become somewhat smitten with the adventurous lady. In Mike Inlet, the black flies were brutal and the camping marginal at best—and love, well, a man in love will not be denied. We stuffed scattered, drying belongings from the pebble beach into our kayaks and were ready to go in half an hour.

When Todd, Keith and I had started our trip 30 days earlier, the packing process had taken more than twice as long. We split the expedition into two parts, first going counterclockwise around Graham Island, returning to our starting point in Queen Charlotte City to re-supply, then continuing in the same direction around Moresby and Kunghit islands. Paddling 460 kilometres around Graham had worked out all our packing kinks for this second leg of the journey.

The proving ground to reach Puffin Cove

Breaking out from the shadow of the mountains, we joined the big blue at its huffing, puffing best. Thirty five-knot gusts drove the swell and began to shove us inexorably toward Puffin Cove. The wind and waves were so strong that within a couple minutes of leaving Mike Inlet it was impossible to backtrack. We were committed. It was six kilometres of huge water or bust. Mike Inlet is one of a handful of safe coves that cut into the 3,000-foot, storm-scraped San Christoval Mountains.

Dropping straight down to water level along the west coast of Moresby Island, the mountains are stark in their nakedness. They were named in 1774 by Captain Juan Perez after St. Christopher, who was known for his protection of travellers. Now we hoped the peaks would cast some of that saintly cover over us.

In between bays on the west coast of Haida Gwaii, rolling buses of swell crash relentlessly against jagged rock, creating boomer zones and clapotis that test even the most skilled paddlers.

Rounding Hippa Island two weeks before, I was pounded over a shallow reef by a rogue, Jaws-sized wave that broke unexpectedly, jettisoning me from my boat. The experience instilled in us a respectful fear every time we ventured out along the perpetually exposed coast.

Ever seen the movie Castaway? There’s a scene where Tom Hanks’ plane has just crashed into the ocean during a storm. He’s clinging to a little yellow rubber raft, the camera pans away, and all you see is this little speck bobbing up and disappearing behind mountains of water in the middle of the sea. That’s what it felt like watching Todd and the Keith, their kayaks seeming more like little paper boats made by children.

Trying to draw focus away from the growing knot of fear in my gut, I looked ahead at the beehive-shaped island that indicated the entrance to Puffin Cove. Gripping the paddle shaft so tightly I thought it would shatter in my hands, I crushed every stroke like it was my last.

Time ground to a halt, our destination only a dream. Though we were hauling ass, it felt like we were paddling on a treadmill. Every time I looked up, the distant cove remained static.

If I let the waves take me, I’d instantly surf seven metres down the face and pound into the trough at the bottom, submerging my kayak halfway. The best thing to do was backpaddle when the wave broke from behind, let it wash over and then stroke like mad before the next one broke. We all tried to stay close—but not too close, as we could end up harpooning each other with our boats. After 40 minutes that seemed like 400, the biggest, baddest wave appeared just as we were about to turn into the lee of Puffin Cove. With Todd and Keith just behind me, a behemoth that was literally 20 metres wide and who knows how high passed underneath and then broke only 10 metres ahead of us in one simultaneous explosion that seemed to turn the entire ocean white. It was a little bon voyage kiss from the North Pacific. Moments later we were in Puffin Cove.

In the Careys’ lagoon, a pioneering life preserved

A narrow channel brought us into a placid lagoon and our jaws dropped. Encircled by perfect powder sand and protected by an amphitheatre of rock, it was like we’d entered Fantasy Island.

I half expected a flock of bronzed women in hula skirts to run down to the beach, greet us with hugs and put leis around our necks. At any moment Ricardo Montalban would appear in his white suit to welcome us while diminutive Tattoo would cry out, “THE KAYAKS! THE KAYAKS!”

The Careys were Americans who sought out a life away from the hustle and bustle of California. After years of searching, they found Puffin Cove. Their cabin is still there, fully intact after 40 years, perched up on a bluff in the corner of the lagoon.

Incurable beachcombers, they accumulated piles of fish floats, buoys, glass balls and other flotsam and jetsam that remain stashed around the foundation. We entered through a trap door via stairs underneath the 12-foot-by-12-foot, greying cedar structure. For all we could tell, Neil and Betty might as well have stepped out a few minutes earlier. Seashells were displayed neatly on the left wall, rows of books and Reader’s Digests lined a ring of shelves. A little wood stove sat in the corner across from the kitchen table, a double mattress and a kid’s bed. Faded bottles of bug repellent, sewing kits, fishing hooks and other bric-a-brac sat around waiting to be used.

Nothing post-dated 1987, the date the Careys’ lease ran out and Parks Canada took over the land to make it part of Gwaii Haanas National Park. For over two decades, the Careys fished, foraged and explored a forgotten coastline, pioneers in every sense of the word.

A logbook indicated we were only the 14th party to visit there in five years. Though we were in one of the world’s great parks, the committing nature of the outer coast deters most kayakers from exploring beyond the sheltered archipelago on the eastern shore of Moresby.

The Careys’ haven is one of the few nooks along the West Coast where there wasn’t once a Haida village. This is most likely because the whole lagoon dries out at low tide, making for poor water access for natives going on expeditions in 100-foot-long cedar canoes. At the height of their civilization, the Haida numbered 20,000 but dwindled to as low as 600 by the mid-20th century, victims of a smallpox epidemic introduced by European traders.

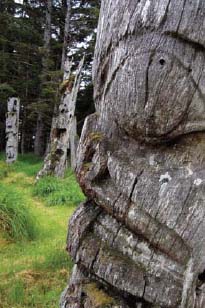

Weathered totems and remnant longhouses remain as the only evidence of their millenia-long inhabitation of a shoreline now patrolled only by black bear and whale.

Even though they weren’t physically visible to us on the outer part of the archipelago, we could feel the spirit of the original people flow strongly through every rock, tree and living being on Haida Gwaii, which means, literally, “Haida Homeland.”

A fitting place to linger before journey’s end

On day 18, we crossed paths with a “super pod” of over a hundred transient orca, their man-sized dorsal fins dropping and rising on all sides of us. Like an ancient tribal greeting party, they came out from a bay in front of the abandoned village of Tian, where archaic totems carved with clamshells and stone still stand.

We bobbed breathlessly amid the procession, staring in wild awe as the creatures disappeared ephemerally into the navy horizon.

The conditions outside Puffin Cove were good for paddling the next day but we decided to linger. With most of the difficulty behind us, we wanted to savour the remaining time we had in that magical land. Lingcod and rockfish practically begged us to throw our lines out, there was endless reading to be done, and we soberly realised we were only a couple of weeks from the end of our journey.

I contemplated what a month of paddling had taught me, how emotions on the outer coast swing between extremes that lead to the purest form of euphoria. One minute you’re paddling for dear life, and the next you find yourself relaxed in a secluded nirvana, your mind bathed in endorphins.

That afternoon, Todd grinned as he served me up a fillet on the beach, fried over fire in one of Betty Carey’s old pans. Keith slowly chewed the white, flaky flesh, gazing quietly out at the breadth of the North Pacific.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak’s Spring 2006 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak’s Spring 2006 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.