There’s a simmering conflict along North American rivers. Unlucky paddlers accessing the hundreds of thousands of miles flowing through private lands have been charged, threatened and even shot. Neil Schulman dives into the murky waters of river access.

Who owns the river?

On July 20th, 2013, Paul Dart, Jr., 48, and a group of family members rented canoes and paddled a stretch of Missouri’s Meramec River. Five hours into their trip, Dart and three others pulled ashore on a gravel bar. Believing Dart and the other men were trespassing, riverfront property owner James Crocker confronted the group with a 9mm pistol. An argument ensued, tempers escalated, and Crocker shot Dart in the face at point-blank range. Dart died en route to the hospital.

The riverside tragedy was a violent boiling-over of a conflict between river users and property owners that had been simmering for years—and not just on the Meramec.

Due to unclear laws, poor communication and cultural divides, waterway conflicts have festered across the nation. If you paddle outside public lands, you’ve likely experienced access issues in some form: a no trespassing sign along the water’s edge, a chain across a portage route, or a creek choked with barbed wire.

In North America, hundreds of thousands of miles of river flow through private lands. Many of those miles are contested. The Meramec murder was shocking for its violence, but not for the nature of the debate.

Crocker believed he was defending his property rights. “It’s my property and I was going to protect it,” Crocker told police. Last spring Crocker was sentenced to 25 years in prison for second-degree murder.

According to the Missouri Conservation Department, Crocker owned the land extending to the center of the riverbed. However, in Missouri, navigable waterways come with an easement that allows the public to use the river, much like a public road or a sidewalk on private property. This easement includes the right to go ashore below the high-water mark, including the gravel bar where Dart was shot.

These legal nuances vary state by state and can be hard to grasp by paddlers, property owners and even law enforcement. Just look at the evidence.

In New York, a lawsuit is resolved after five years in court. At the center of the debate was a canoeist paddling on a creek through private property that connects two parts of a state forest preserve.

In North Carolina, landowners stretched a cattle fence topped with razor wire across the North Fork of the Chattooga, a designated National Wild and Scenic River.

The right to float the South Fork of the Saluda River in South Carolina continues to work its way through the courts. Paddlers have received trespassing citations on New York’s famed Au Sable River, only to have the charges dropped. Disputes have also led to the arrests of fishermen on both the classic John Day and Trask rivers in Oregon.

When streams flow through public land, the situation is simple. Unfortunately, most rivers in North America flow through some private property, where they can become tangled in a legal netherworld, awaiting clear rulings or the settlement of lawsuits.

Legal eddies

The public’s right to use rivers rests on a legal concept called navigability. In the legal sense of the word, the principle is that navigable rivers are akin to roads. Even if the riverbed is privately owned, the water is owned by the state, and the public has a right to use navigable rivers.

If that seems simple, it’s not.

“There are four types of navigability, and different tests, laws and lots of confusion [when applying the concept],” says Kevin Colburn, stewardship director of American Whitewater, a national body that promotes conservation and river access.

In Oregon, for example, the Division of State Lands asserts that a navigable river is “a river that was or could have been used to transport people or goods” at the time of Oregon’s statehood in 1859.

If that evokes visions of barges plying the Columbia, Mississippi and St. Lawrence, that’s not the case, says Eric Leaper of the National Association for Rivers. “A small steep river or creek, where a canoe could carry beaver pelts or small sections of logs, is navigable. It could be ankle deep and might not even be kayakable in today’s world. The Supreme Court has said that counts.”

Bureaucracy has dragged far behind the upward trend of river use across North America. Of Oregon’s 236 rivers and creeks, navigability rulings have been made on just 12 since statehood. The other 200-plus disputable rivers await navigability studies at an expected cost of over $10 million.

Who’s in charge

Confusion arises because whether state or federal law applies is open to debate. Leaper contends that a federally-established right of the public to use rivers stems from Supreme Court rulings ranging from 1789 to 1981.

“Landowners and their lawyers want you to believe that it’s a state-by-state issue because they think they have decent chance to win in state court,” says Leaper. Other river advocate groups read the legal landscape in different ways.

“It’s a terrible, time-consuming and conflict-based way to resolve the issue, with personal costs to people.”

Since trespassing charges generally fall under local jurisdictions and navigability rulings are done by states, state courts have ended up handling most river access cases. “A state court typically won’t get into federal law unless the river users say that is what their right is based on,” Leaper says. State laws and courts tend to mirror their state’s political culture. Politically conservative states tend to treat property rights as sacrosanct, while states with progressive voters and strong outdoor recreation culture tend to be more sympathetic to paddlers, fishermen and public use.

In Canada, the right to access waterways through private land is also complicated. “Anyone can paddle on the waterways. There is often a shoreline public right-of-way, 66 feet deep, that is public access,” says Graham Ketcheson, executive director of Paddle Canada. “But in the last 35 years, in the province of Ontario, people have been able to buy the frontage from some municipal governments and own it right down to the high waterline. That’s where it gets complicated. How does a paddler know what is public or private when they want to stop?”

Nobody knows

In the U.S., where there is a right to float, river users are also allowed to use the riverbed below the high-water mark, as Dart did on the Meramec. But what about scouting and portaging, which often involve stepping above the high water mark? Those laws vary. In Montana, it’s legal. In North Carolina, the law isn’t clear, says Leaper.

The legal morass doesn’t end there. Many states are awash in deeds that show property lines running to the low-water mark or centerlines of rivers. This means landowners are paying property tax on land that is underwater, and, if the public can use the river, over which they have little control. Some landowners worry about liability from public use of their property, or the effects on ranching operations.

Where’s it headed?

As river use in North America grows, comprehensive legal rulings have remained elusive. “A certain amount of court cases will slowly work their way through the system,” says Colburn. “It’s a terrible, time-consuming and conflict-based way to resolve the issue, with personal costs to people.”

In 2009, Phil Brown, a magazine editor from Saranac Lake, New York, paddled a short stretch of Shingle Shanty Brook through private land as part of a two-day trip through the William C. Whitney Wilderness, a state forest preserve. His trip was done to make a point.

“I believed I had the right to paddle the short section through private land, even though it was posted,” says Brown.

The year after, state officials determined that the waterway was open to the public. However, that didn’t stop the landowners from serving Brown a trespass lawsuit in 2010. The court dismissed the suit, but the landowners appealed the decision and put up cameras. A final ruling was made on January 15, almost six years after the trip that launched the dispute. The court ruled in Brown’s favor 3-2.

“I’m grateful to New York State officials for taking my side in this case,” he adds. “It gives me hope that, in this state at least, paddlers’ rights will be defended. With luck, New York will set an example for other states.” The landowners may yet appeal the ruling.

Heart of conflict

Amidst these muddied waters, two things are clear. First, the legal aspects can be befuddling to everyday river users, with few avenues for resolution.

“It’s difficult to get [these disputes] settled out of court by normal people. But normal people paddle rivers and normal people own land,” says Colburn. Even the most basic rule of thumb—don’t trespass where posted—can create problems, since landowners may assert rights they don’t actually have.

“The no trespassing guideline is useful if you want to avoid conflicts, but it’s not useful if you are within your rights and want to assert them,” says Colburn.

“We encourage paddlers to not turn a blind eye to others who are setting a bad example.”

Like Brown, paddlers can be forced to make individual choices about when to assert what they believe are their rights or when to turn the other cheek. When paddlers avoid conflict, they may leave property owners with mistaken belief that they have the right to restrict access to rivers or gravel bars.

Second, river conflicts often mirror larger fault lines that divide North American society: rural and urban, progressive and conservative, rich and poor, and divisions between environmental advocates and land-based industries.

“Urban paddlers in modern boats can seem like an invasion to a rural landowner,” says Leaper, adding that this is especially true where past conflicts have put urban and rural concerns at odds. The simultaneous rise in outdoor recreation and property-rights rhetoric has only intensified the fervor.

Paddlers’ behavior can also make relations worse. Rivers that fill with drunken revelers in summer, like Oregon’s Clackamas and to a lesser extent, the Meramec, tend to have more conflict. And what may seem like normal river behavior to some paddlers—discretely changing clothes at the put-in or a pee break on a gravel bar—can irk locals.

The communication gap

When taken as individual issues, fences, noise, scouting rapids, and a lack of decorum sound like minor disagreements that can be resolved in conversation without lawsuits, let alone guns. So why does it get out of hand?

One factor is the decentralized cultures of both sides. Most disputes originate with individual landowners, of whom there are millions. Paddling clubs and fishing organizations, the strongest partners in communicating with landowners, represent a small fraction of river users. Few mechanisms exist to communicate when problems arise. Subtle behavior changes that could reduce tension—changing parking locations, adding a garbage bin at the take-out, or scouting from river left—often aren’t communicated to the masses.

This lack of communication means a lot of missed opportunities. Colburn cites an instance where a landowner blocked a river with a fence to keep livestock on his land.

“There are ways to keep cattle from moving that leave the river open and are no inconvenience to paddlers,” Colburn says. As an example on the other side of the debate, “if paddlers changing clothes is an issue, let’s build a changing house.” Poor communication leaves both sides frustrated and entrenched.

When communication happens early, tensions often ease. Advocacy group Whitewater Ontario works to resolve access concerns before they can snowball.

Neil Schulman is a paddler and conservationist living in Portland, Oregon.

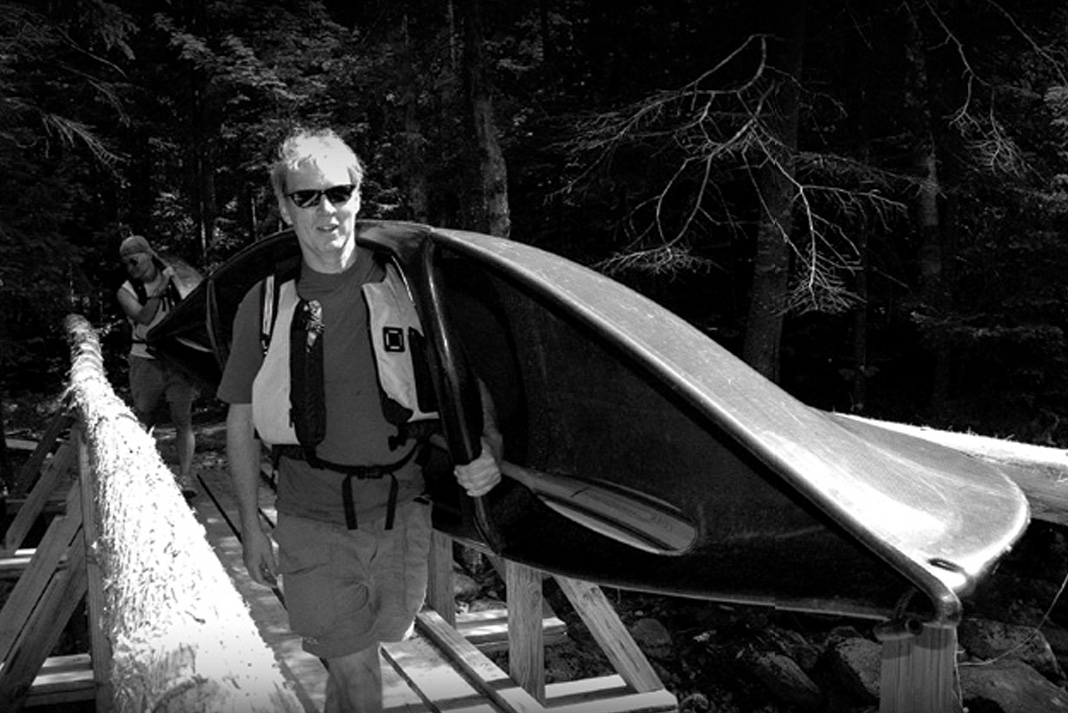

If you paddle outside public lands, you’ve likely experienced river access issues in some form. | Feature photo: iStock

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.