When Phil Brown set out on a two-day canoe trip in the heart of the Adirondacks in 2009, he thought it might make a good story. What he got instead was a three-year legal battle that ultimately upheld the public’s right to make that journey by boat, even though it cuts through private property.

No man’s land: Paddler fights for the right to paddle

The decision, issued by a state judge at the end of February, sheds a little light on the murky topic of waterway navigability in the United States. If the ruling stands, other paddlers in New York may be emboldened to challenge routes marked as private, and landowners may think twice before blocking access.

Brown is editor of the Adirondack Explorer, a magazine that covers the environment and recreation in New York’s six-million-acre Adirondack Park. As part of a route between Little Tupper Lake and Lake Lila in the state’s Whitney Wilderness, Brown paddled along a remote stretch including three smaller waterways.

The owners of the land intersected by those waterways had hung no trespassing signs and cables to deter paddlers. Brown could have taken a mile-long detour across state-owned land to avoid those waters, but didn’t.

“I had done my research and had come to the conclusion that this waterway was likely navigable and therefore open to the public,” says Brown, who wrote an article called Testing the Legal Waters based on his trip.

When the landowners sued him for trespass they contended that the waterway—big enough for a canoe or kayak but little else—was too small for commercial use, an historic method of determining navigability in the United States.

Brown disagreed with that assessment. So did New York officials, who joined Brown in the case. Justice Richard T. Aulisi agreed: “Practical utility for travel or transport,” he wrote, are valid measures of navigability. And making that ruling on such a small waterway makes it clear that recreation rights apply to even the smallest craft.

Technically, Aulisi’s ruling applies only to the waterway involved in the case, as navigability is determined on a case-by-case basis. But other courts may look to Aulisi’s decision as a guide if future cases are filed, says John Caffry, Brown’s lawyer.

Attorney Neil Woodworth says the ruling is good news for paddlers across the state. If the ruling stands, “a fair number of paddlers will begin to try waterways where there had been posted signs and barbed wire,” he adds.

While state officials celebrated the ruling as a victory for the public’s right to access natural resources, they urged paddlers to be cautious. “The case does not mean that every waterway in the Adirondacks is now open to paddlers, nor does it mean that no trespassing signs on waterways can now be routinely ignored,” a spokeswoman for the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation wrote in an email.

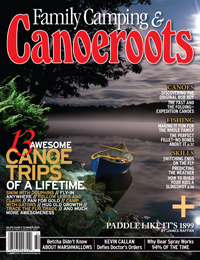

Paddling into no man’s land. | Feature photo: Susan Bibeau/Adirondack Explorer

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2013 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2013 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.